The players and the game

The basics about the sector

Download the full chapter in PDF

Why it matters

Why does this matter to your audience?

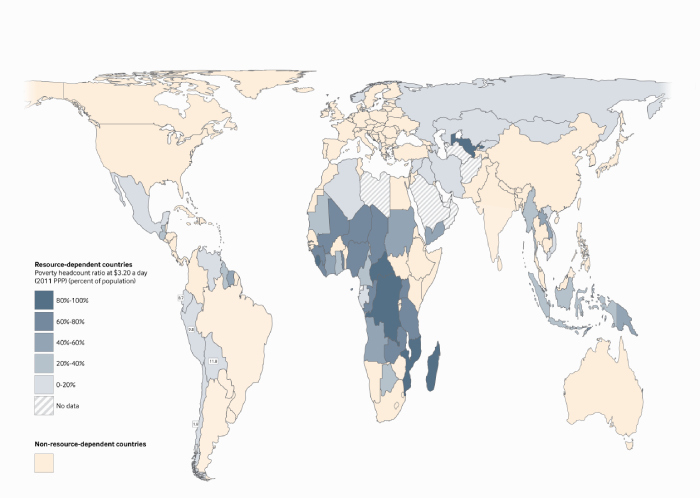

- The extraction of oil, gas and minerals generates billions of dollars in revenue every year. This incredible wealth could be put to good use for the 1.8 billion people living in poverty in resource-producing countries.

- For most countries, natural resource endowment has not been a blessing. Extractive activities have brought the “resource curse”, including environmental destruction, increased levels of armed conflict, economic instability and slow growth, corruption and weak public institutions.

- Corruption and poor management are central causes behind this resource curse. The good news is much of this can be prevented by strong, transparent decision making. When citizens are informed about the choices and risks governments are taking, they can demand institutions, rules and practices that foster better long-term development.

- While governments should be the major decision-makers in the sector, some private extractive companies are so large and advanced in expertise that they dwarf many other industries and can sway public decision making. The six leading extractive companies bring in profits so large that they are comparable to the GDPs of many medium-sized countries. ExxonMobil alone brought in USD 20.8 billion in earnings for 2018.

The basics

Natural resource extraction projects have distinct phases, from locating deposits, through their extraction, processing and marketing, to their closure. Each project involves key players, including governments, state-owned enterprises, regulators, international bodies and private companies of different size and function. To report on the extractive sector, it is important to understand these players and their roles at each stage of a project. By shedding light on whether players are fulfilling their obligations to all stakeholders—including local communities—reporters can help provide the transparency needed to prevent the “resource curse”, which describes the failure of many resource-rich countries to benefit fully from their mineral or oil wealth.

-

The process of extraction

The oil and gas industry

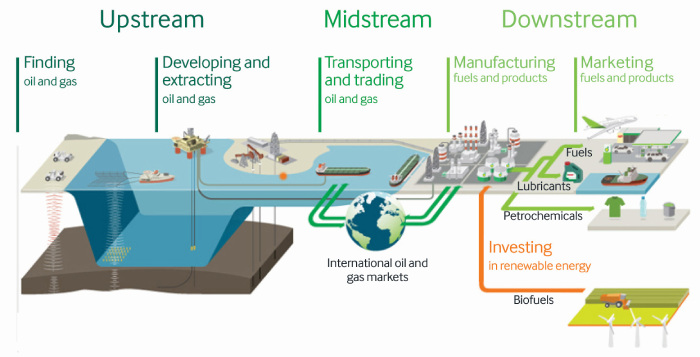

Oil and gas: upstream, midstream and downstream production

The oil and gas production process is divided into three phases: upstream, midstream and downstream.

Upstream

“Upstream” production consists of locating crude oil or gas and getting them out of the ground at the wellhead. This is typically the most capital-intensive phase of production, with high costs up front—as well as the most lucrative part of the value chain.

There are several phases of the upstream process which are often considered the lifecycle of a project. They start with exploration and appraisal, determining whether a country’s resources are commercially viable to extract. Depending on how confident the company is that it would make money from getting the oil out of the ground and taking it to market, it will describe its reserves as “proven” (90 percent certainty), “probable” (at least 50 percent certainty) and “unprovable” or “possible” (between 10 and 50 percent certainty).

The next phase, development, begins when the company is convinced that the project can be profitable and the government gives it a license to proceed. During this phase, a company often digs additional test wells, makes environmental impact assessments and gives plans to the government about how the project will proceed. The company also often needs to use this time to raise money to pay for all the equipment needed for the project.

Next, a company will start the production process, which includes getting the oil or gas out of the ground and transporting it towards a market. The production phase is usually when the most revenue is generated, as costs start to stabilize after a few years. Most oil and gas projects follow a trend of production that starts slowly, peaks and then reduces, as shown in the sample production curve below.

Production profile of a typical oil field. (Source: NRGI) The last phase of an oil project is the decommissioning or abandonment phase, in which the company is responsible for closing the wells and restoring environmental impacts. The extent of company responsibility in this phase depends on the contract it has with the government, but there are usually requirements for the company to remove its equipment and leave the area in a safe way that reduces risk of future environmental problems like seepage or gas leaks.

Midstream

“Midstream” encompasses the processes in between the upstream and downstream, which is mostly storage and transportation of oil and natural gas. These are transported via pipeline or ship. To be shipped, gas must first be significantly cooled so it becomes liquid, called liquefied natural gas (LNG). Once LNG is shipped to its destination, it is turned back into gas.Downstream

Minerals that are unaltered since coming out of the ground are referred to as raw materials. Transforming raw materials into a format that can be used by consumers is the first step of the downstream phase, called refining. Refining involves separating out a mineral from impurities and unwanted substances. In the case of oil, this often means taking out water or sulfur. For gas, the process focuses on concentrating the methane so it can be used. This process often takes place at refineries—facilities that convert the “crude oil” that comes out of the ground into products like jet fuel or fertilizer. The downstream phase also includes marketing, as it involves turning the resource into something that the end-user can purchase and consume.The figure below gives an overview of the oil value chain:

Oil value chain describing BP’s business model. (Source: BP) Many energy companies work in multiple parts of the chain at once. This means more chances for efficiencies and, sometimes, more chances for corruption. This guide focuses on the upstream stages of mineral production, where natural resource producing countries have the greatest interests, and the most say.

→ Watch this 15-minute video about the oil and gas development cycle.

The mining industry

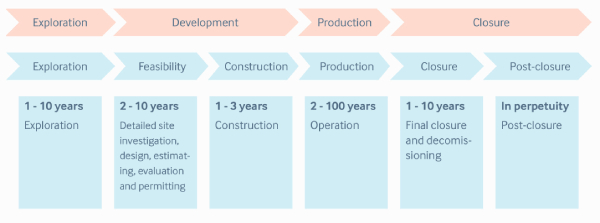

Phases of a mining project: Exploration, development, production and closure.

Exploration

Mining projects have four phases. They start with exploration, during which the company tries to understand what types of minerals may exist in the ground and how easy or hard they would be to extract. This often begins with aerial studies and mapping, and seismic analysis, using sound waves to better understand the composition and density of rocks. Next companies often extract core samples that give a sense of what type of minerals exist in different layers of the ground. The government often has rules about what activities companies are allowed to do before they have to report back to the government or ask for additional permission.

The goal of a company during exploration is to understand what type of minerals are likely to occur and the cost associated with extracting them. Potential extraction projects viewed as likely to be successful are classified as either a “proven reserve” or “measured resources”, meaning the company is highly confident it can make a profit taking the mineral to market. “Probable reserves” or “indicated resources” mean there is reasonable confidence that the minerals exist and can be extracted. “Inferred resources” mean there is reason to believe there might be a certain amount or type of resource, but it cannot be confirmed.Development

The next phase of the extraction process is the development phase. This begins with a company understanding the feasibility of the project, investigating what type of mine to develop, how to deal with the waste, how to get the mineral from the mine site to market, and the potential social and environmental costs. Companies are usually required to submit a feasibility study to the government and their investors before beginning construction. In most countries, the government has a responsibility to review and approve these studies, but sometimes they are treated as a formality and have little influence over whether a project is granted a license.Production

Once the mineral deposit is deemed commercially viable and the appropriate contracts have been signed, the company begins production, with some mines lasting up to 100 years.Closure

The extraction company is responsible for closing the mine and making the area around it safe, including getting rid of waste. This closure or rehabilitation phase is often very important to surrounding communities.The image below gives an overview of the lifecycle of a mining project:

Typical lifecycle of a mining project. (Source: NRGI) → This 10-minute video explores the project development phase of a mine, while this infographic visualizes the lifecycle of a mineral discovery.

-

The players

To report on the extractive sector, it is important to understand the key players and their roles—from governments, state-owned enterprises and regulators, to international bodies and private companies of different size and function.

The state

In most countries, the state is the owner of all natural resources in or under the ground or sea within the country’s territory. When natural resources are discovered in a country, governments often invite companies with experience in resource extraction to explore and extract the product. Many governments do this because they do not have the expertise, capital or equipment to bring resources out of the ground and to market. In this situation, the government makes money either by retaining ownership of a portion of the resources the company has extracted, or by charging taxes and royalties on the company’s profits.State-owned enterprises

Countries often create state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in order to participate in resource extraction. In oil and gas, these are called National Oil Companies (NOCs). According to the World Bank, NOCs control about 80 percent of global oil reserves and 75 percent of the world’s oil production. Some of the biggest oil companies in the world are NOCs, like China’s Sinopec and Saudi Arabia’s Saudi Aramco. NOCs can be involved in all parts of the production process, from extraction to refining to marketing and trading. Some just work within their home country, while others, like Malaysia’s Petronas, also work abroad.

As with oil and gas, SOEs also play a key role in mining, as with China’s Shenhua, Mongolia’s National Mining Corporation and Coal India.

Governments see SOEs as a key tool for promoting local content—a way to grow the country’s expertise in a lucrative industry and create high-paying jobs. SOEs also allow countries to increase their revenue share from natural resources and to monitor more closely the private-sector partners working in their natural resource sectors.

SOEs can be powerful vehicles for development and building human capacity (see Chapter 3), but they can create risks around accountability for how money is managed. They can also take public revenue down some unanticipated paths. Sitting at the crossroads of public decision making and vast revenue streams, an SOE can often turn into a hub of corruption or mismanagement.International oil companies: The giants

International Oil Companies (IOCs) are active at all steps of the supply chain, from exploration and production to refining and marketing. Among them, the “giants” operate in multiple regions, and are big enough to influence global oil supply and prices. On the Forbes annual ranking of the world’s largest public companies, the oil giants regularly feature among the top 30 biggest companies. They count among the most profitable private companies ever, earning billions of dollars every year. This gives them powerful influence in the industry and beyond.The size of an IOC can be measured in two ways:

- By market value (or market capitalization), calculated by multiplying the number of the company’s shares by the value of one share.

- By the size of its mineral reserves. Publicly listed companies on the New York Stock Exchange, for example, have to report their reserves each year to the US Securities and Exchange Commission.

The giants include ExxonMobil (United States), Royal Dutch Shell (UK and Holland), ConocoPhillips (United States), Chevron (United States), British Petroleum (UK), Total (France) and ENI (Italy).

Smaller oil multinationals

While NOCs and IOCs control the majority of the global oil production, smaller multinational oil companies are making some of the most important new discoveries around the world. These companies tend to focus exclusively on the upstream sector and are sometimes called “the independents”.

For example, Houston-based independent Noble Gas made a key deep-water gas discovery in the Eastern Mediterranean in 2011. In East Africa, Canada-based African Energy Corp and the UK’s Tullow Oil have taken the lead in opening up the region for commercial production. Tullow—which calls itself “Africa’s Leading Independent Oil Company”—is also active in West Africa, in countries such as Ghana.

These smaller companies tend to develop technical expertise in one area of extraction, such as deep-water drilling. They often go into regions that bigger companies might see as unproven or too risky. If an independent does make a major find through one of these ventures, larger IOCs often become involved in joint partnerships later in the process.Mining companies

The mining sector also contains a mix of large and small companies. The larger players—also called the majors—include Glencore, BHP Billiton, Vale and Rio Tinto. In mining, the biggest players are private, with some larger companies extracting many different minerals, while others specialize in one or a few. Freeport, for example, specializes in copper and gold.

While mining does have a few larger companies, unlike the oil sector, it is dominated by hundreds of smaller companies, called the juniors, which tend to focus on exploration. Their access to capital is much more limited than the giants, and they rely on project-specific equity financing to fund new operations. A few also produce minerals on their own or in collaboration with other companies.International bodies

In oil and gas, the Organization of Petroleum Producing States (OPEC), is a leading player. While its influence has fallen in recent years, this international body aims to limit countries to various levels of oil production, so as to influence the global oil price. The group currently has 14 member countries, which together control 80 percent of the world’s proven reserves and one-third of production. Saudi Arabia is typically the most active and powerful member. Russia is not part of OPEC, but it often cooperates with it.

In mining, the powerful body is the International Council of Mining and Minerals, an organization composed mostly of large extraction companies. Its influence on standards in the industry is gradually increasing, though junior companies generally lack the resources to comply with these high standards. With the Toronto Stock Exchange providing up to 60 percent of mining financing globally, Canadian mining companies have a large global presence and the Mining Association of Canada has a significant influence on industry standards as well.Services companies

Service companies provide specialized services to larger extractive companies and are increasingly relevant players in the oil, gas and mining sectors. Ongoing NRGI research shows that between 50 and 90 percent of the costs of a typical oil, gas or mining project go to third-party suppliers of goods and services.These range from small companies providing food or transport, to huge multinationals providing specialist services like seismic testing, drilling, engineering and construction. These multinationals include Schlumberger, Halliburton and Baker Hughes. They are not exempt from corruption scandals, normally following suspicious bidding processes for contracts. For example, Halliburton was found guilty by the American Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) of having violated the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act in Angola in 2017. The Financial Times reported that Halliburton had to pay a USD 29.2 million fine for having gained questionable access to lucrative contracts with the national oil company Sonangol. To fulfil local content obligations, Halliburton paid $3.7 million over a seven-month period to a local Angolan company. This was owned by a former Halliburton employee, who was also a friend and neighbor of a Sonangol official with the power to veto or reduce subcontracts awarded to Halliburton by large international oil companies. That official later approved Halliburton’s local content proposal.

→ Read this NRGI report to find out more about the governance of extractive industries suppliers.

Commodity trading companies

The commodity trader’s role is to get the natural resources to the market where they can be sold on. Commodity traders make a profit by buying oil, gas or minerals and selling them to those who can supply end users, such as refineries. However, traders get a margin that theoretically could have been captured by the government or extraction company if either marketed the commodity itself.

Despite sometimes operating in logistically or politically difficult environments, large commodity trading houses can find the industry highly lucrative, as they make more than $100 billion in annual revenues. Often based in Switzerland, London or Singapore, these include Glencore, Xstrata, Vitol, Cargill, Trafigura, Gunvor, Koch Industries, Mercuria and Phibro.Many oil multinationals and NOCs also have trading arms, as can banks and hedge funds.

Some small exporters choose to hire a trading company to market their oil or minerals on their behalf. In Chad, for example, the Swiss trading company Glencore buys 100 percent of the oil sold by the government, making payments accounting for 16 percent of the Chadian government’s revenues. The traders have the experience to find customers for the specific crude or mineral produced and are also often experts in dealing with challenging logistics. -

The resource curse

Despite the great wealth natural resource extraction can generate, the discovery of a high-value resource can also bring about lower rates of economic growth and cause significant political and social challenges. This “resource curse” describes the failure of many resource-rich countries to benefit fully from their mineral or oil wealth. Problems can sometimes start even before any mineral leaves the ground (known as the “presource curse”). Secrecy is a key driver of the resource curse, making greater transparency central to tackling it.

Common causes and effects of the resource curse

Weak incentives for democratic accountability

Political scientists find that governments are more responsive to citizen demands when government spending is dependent on citizen taxation. People want to know what happens to their taxes. There is usually less direct citizen taxation when public revenues come from oil, gas, and mining industries, which reduces public pressure on politicians to be accountable. This problem is made worse when citizens are not informed about resource revenues and their use. The result is a tendency towards authoritarianism in resource-rich countries. In Eurasia, for example, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan are all resource-dependent, while ranking near the bottom of Freedom House’s ratings for political and civil liberties.

Heightened risk of conflict

Oil, gas and mineral producing countries are more likely to experience armed conflict. This can be for several reasons, including difficulty deciding who should benefit from extraction, and groups fighting for control of the resources. Libya since the fall of Colonel Gaddafi is a good illustration of how resource extraction can undermine political stability, and how instability affects extraction. Since the revolution of 2011, Libya’s oil and gas resources have been held hostage by different groups fighting for control over the country. Some have used disruptions to oil production to maintain instability, from which they benefit.

Inefficient government spending and borrowing

Revenues from oil, gas and mining are very unpredictable, because of changes in commodity prices and fluctuations in production. If countries do not plan for this volatility, they can end up in debt for having over-borrowed and over-spent their budget in times of boom. Oil-rich Congo Brazzaville regularly gets into trouble through unwise over-spending. The oil sector accounts for 80 percent of the state budget, but weak financial discipline has generated high levels of debt, forcing the country to default on some of its loans. In 2019, to obtain an IMF loan in order to overcome its most recent debt crisis, the government had to commit to reforming management of its oil revenues.

Challenges of sustaining other sectors besides extraction

By focusing on the lucrative extractive sector and neglecting other important economic areas, such as farming or manufacturing, countries often experience poor growth following a natural resource discovery. One reason for this is so-called “Dutch Disease,” when a large increase in resource revenues can create inflation that hurts other sectors of the economy. Developing other sectors of the economy (“economic diversification”) can also be hard because the new extractive industry tends to attract some of a country’s top workers and entrepreneurs. Insufficient economic diversification has meant that a country like Venezuela, where oil makes up 98 percent of exports, has become extremely vulnerable to international dynamics affecting its oil production. The combination of low commodity prices and international sanctions on the country’s energy industry have caused the country to spiral into debt and hyperinflation in recent years.

Limited government income from resources

In some countries, the terms of the deal between an extraction company and the government are unfairly beneficial to the company. This can happen because a government is desperate to attract initial investors or because it had less access to information about the industry or the country’s mineral deposits than the company. Even when there is a fair deal, many governments struggle to fully recover the amount due, either because of inefficient collection practices or tax loopholes, such as transfer pricing (see Chapter 4), which affect government revenue even in developed countries with mature tax offices, such as Australia. The Australian Taxation Office regularly files cases against multinational extractive companies, challenging their abusive tax practices in the hope of recovering hundreds of millions of dollars in unpaid taxes.

Empowered elites and weakened public institutions

In comparison to other sectors of the economy, oil, gas and mining projects tend to create more opportunities for rent-seeking by the elites. This means that elites seek to capture the revenue flows from the extractive sector to increase their own wealth, without any benefit to society. This is possible when there are weak checks and balances in place to scrutinize what public officials and civil servants do. Rent-seeking tends to further weaken public institutions, as elites strengthen their positions of power through corruption. Public service delivery suffers as a result. In Myanmar, the military junta for many years used the natural resource sector to capture important revenues, taking advantage of weak accountability mechanisms to bypass Myanmar’s national budget. NRGI research in 2018 showed how billions of dollars were unaccounted for after they had been transferred by natural resource SOEs into so-called “Other Accounts”. The country’s lack of transparency and oversight resulted in important misallocation of public funds.

Social and environmental problems

Without proper management, many countries see natural resource extraction cause devastating environmental impacts. The destruction of land, including by seismic disturbances, is often cause for conflict between companies and communities living nearby, and can cause human rights violations. In Brazil, for instance, weak enforcement of compliance rules for dam safety caused catastrophic loss of life and environmental damage when tailings dams collapsed at mines operated by the mining company Vale. In 2015, the Fundao tailings dam failed at an iron ore mine operated through a joint venture between Vale and BHP Billiton. Nineteen people died and several hundred were displaced in one of Brazil’s worst environmental disasters. In 2019, the collapse of the tailings dam at the Vale-owned Brumadinho mine killed nearly 300 people. Tensions and health hazards also result from the large influx of people seeking jobs and business with extraction projects. In this context, studies show that women not only bear the brunt of negative impacts, they also experience fewer of the potential benefits, such as employment.

The presource curse

Read more

In some countries, trouble begins before the revenues start to flow. With the “presource curse”, just the discovery of a precious mineral can potentially cause government over-borrowing and over-spending. A country’s vulnerability to the presource curse can be indicated by the strength of its governance structures, such as independent oversight bodies and clear regulations that are well enforced. Countries with weaker political institutions often find their average growth rates slow after a giant oil and gas discovery, due to lack of oversight of spending and revenue use. For example:- Ghana – In 2009 the country’s economic growth was steady — about seven percent between 2003 and 2013. More recently it’s been below four percent. What changed? Oil. Or rather, the promise of oil. After major oil discoveries in 2007 and 2010, the country began borrowing heavily — as well as spending heavily. As for savings, while the country saved USD 484 million in oil revenues for a rainy day, it also borrowed $4.5 billion on international markets. Since 2015 the country has been in an IMF support program.

- Mozambique – In 2009 Mozambique’s growth averaged 6 percent. Then the country discovered gas — the largest offshore gas deposits in sub-Saharan Africa. Following these discoveries, forecasters put growth on a path above 7 percent. But by 2016, growth was down to 3 percent, the result of massive off-budget borrowing.

However, Tanzania experienced high levels of economic growth, from 6 to 7 percent, after it discovered off-shore gas in 2010. This was thanks to a sensible government response, which maintained low levels of debt and committed to fiscal sustainability by legislating fiscal rules.

→ Find out more about the presource curse in a recent NRGI paper.

Transparency: the first step towards addressing the resource curse

It takes a diverse set of efforts to tackle the resource curse. A key one is the proactive disclosure of information by governments and companies about the management of natural resources. Greater openness can increase oversight, improve trust between multiple actors and reduce waste. For example, in Norway, relevant, timely and accessible information is made available to the public about many important aspects of the oil sector through a centralized online platform, Norsk Petroleum. Despite having one of the highest taxation rates in the world, this transparency means Norway has no difficulty in attracting high-profile investors. Where there is a lack of transparency, this often indicates a lack of political will to manage oil, gas and minerals in a responsible way that best serves the public interest.

→ Watch this 10-minute video for more on the arguments for openness in the oil, gas and mining industries.

For transparency to lead to accountability, meaning that citizens can effectively ensure that governments and companies keep their promises, information needs to be presented in plain language and in ways appropriate for different stakeholders. It also needs to be timely and accurate, so that stakeholders can use the data to inform decision making.

Since the early 2000s, a number of transparency efforts at the national and international level have pushed for greater disclosure in the oil, gas and mining industries. Multilateral organizations such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) or the International Monetary Fund (IMF) provide states with guidance on how to manage their extractive sector more transparently. The global civil society coalition Publish What You Pay has been successful in pushing for legislation forcing extractive companies listed on stock exchanges in the European Union, Norway, Switzerland and Canada to publish their payments to governments. There are also several voluntary initiatives, including the Open Government Partnership and the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), that support countries in their efforts to ensure greater transparency.→ This 11-minute video profiles different governance initiatives relevant to extraction.

The EITI is the most prominent transparency effort in the extractive sector. Launched in 2002, it now has over 50 member states. By setting out disclosure requirements, the EITI Standard prescribes how member countries should report on their oil, gas and mining sectors. EITI reporting covers all aspects of the upstream extractive sector, from how extraction licenses are allocated, to how revenues make their way through the government and benefit the public. It is an important source of information for the public and the media. In many instances, EITI reporting has shed light for the first time on the management of a country’s natural resources—for example, in Myanmar, where EITI reports provided unprecedented information about the various SOEs active in the sector.

(Source: EITI) Countries willing to join the EITI commit not only to disclose information about the management of their natural resources, but also to set up a multi-stakeholder group that oversees the reporting process. The multi-stakeholder group has representatives from extractive companies, the government and local civil society, who all have an equal say in decision making. In many EITI countries, including Ghana and Myanmar, this three-way dialogue has developed trust among different parties in the sector and has helped drive reforms.

→ To find out more about the EITI and its evolution, watch this video interview with the former head of the EITI International Secretariat. EITI country pages are a helpful tool for journalists to track implementation of the EITI Standard in individual countries.

Story leads

In this first chapter, journalists can read general tips on how to prepare for a story on natural resources, including on how to stay safe when reporting about the extractive sector. The next chapters suggest specific reporting angles and research steps to help journalists generate ideas for compelling stories and to pursue them.

Finding ideas for a story

Ideas for a story on natural resources can come from many places. Sometimes the BBC, Reuters, Bloomberg or CNN may provide news that reporters want to follow up on. Or reporters might be interested in pursuing questions raised in an earlier story. Inspiration can come from talking to sources or meeting influential people. It can strike when receiving a press release from government, extractive companies, oversight institutions involved in the sector or watchdog groups releasing new analysis. Whistleblowers might approach journalists to share relevant information. Developments in the sector – new legislation discussed in parliament, or a licensing round, etc. – can help generate reporting angles. Reporters can also use current events as a starting point to generate a story about natural resources. For instance, elections offer an opportunity to take stock of government commitments on extractive sector reform and maybe uncover broken promises. Or an anecdote about a school funded by the national oil company could lead to a bigger story on the multiple roles of the state-owned company.

To assess whether their idea is worth developing further, journalists might want to check two important elements that make up strong stories:

- Newsworthiness: Does the story relate to recent events or present new information about past developments?

- Public interest: Is the story in the public interest? It must meet at least one of these criteria in order to qualify:

- The story highlights or covers in detail bad governance, crime, corruption, or the failure of regulatory bodies or instruments.

- It provides information that allows the audience to make more informed decisions about matters of public importance.

- It seeks to protect public health and safety or prevent the public from being misled.

- It highlights issues of freedom of expression.

Making a plan

Journalists can cover extraction through news, feature or investigative articles. Independently of the format, identifying relevant information sources – both human and documentary – is critical to build a solid story. The research steps in the following chapters and the “Sources” sections in each chapter offer subject-specific guidance on where reporters can look for information for their reporting.

A few general considerations to keep in mind when working with sources:

- Human sources: Are the sources named? Are they quoted? Are they credible – even when not named to protect them? Are there several?

- Documentary sources: Does the story include an independent documentary source?

- Fact checking: Have the facts presented by sources been checked? Are they correct?

Security considerations

Read moreWith attacks against journalists and the free press on the rise in many countries, reporting on the extractive sector, where many powerful interests meet, can be risky. Shining a light on lucrative deals, uncovering abusive environmental practices or questioning whether a local community has been properly consulted can generate different types of threat—from physical to legal—for reporters, their media outlets and even their families. It is essential to be aware of these challenges and to try to reduce their potential impact through proper planning and protection measures.

It is important to review potential risks associated with a particular report. Depending on how sensitive the issue is and the resources available to help investigate it, a journalist might need to reframe the story’s leading question. Key resources to consider include existing contacts, and financial and legal means to withstand potential retaliation. These need to be balanced against expected gains in income and audience if a media outlet breaks a big story. Risks associated with the tools, information sources and research techniques a story requires can mean reporters need alternative approaches to obtain the necessary data.

Journalists also need to weigh up the advantages and potential dangers of working with others on a story. Can a source really be trusted to protect a reporter’s interests and safety? Journalists working on extractive stories always need to be mindful of the physical and technical environment in which they operate, as the investigation can leave traces that can put a reporter, their colleagues or information sources at risk of reprisal. A reporter’s own identity will influence likely threats—for example, female reporters can face different risks from their male colleagues.

Useful tools and approaches for assessing risk and staying safe include:

- The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) Security Guide, which includes helpful advice on how to consider safety questions.

- Security training before entering a high-risk environment, such as a conflict zone or violent demonstration. The ACOS (A Culture of Safety) Alliance lists organizations that can offer this type of training on its resources page.

- Digital security training—for example, through Totem, an online platform that helps journalists and activists navigate digital security and privacy tools.

- Security-in-a-Box, a joint project between Tactical Tech and Frontline Defenders, presents useful tips to stay safe online.

- Tests put together by the digital helpdesk of Reporters Without Borders, to help journalists see whether they need training.

- Tactical Tech’s investigation kit, Exposing the Invisible, which gives a systematic overview of risks during the research phase and advice on various safeguards to use during an investigation.

- The handbook put together by UNESCO and Reporters Without Borders, which gives valuable advice for high-risk environments.

Before taking any risks, it is essential that reporters build relationships with trusted emergency contacts, including legal support, medical expertise and diplomatic or financial support. Reporters employed by a media outlet should discuss these options with their editors, while freelance journalists should contact relevant trade unions and professional bodies. International organizations such as Reporters Without Borders and the CPJ also specialize in providing emergency response. They usually apply a screening process before offering assistance, so having been in touch with them beforehand can help journalists access support.

Preparing the story

The checklist below builds on basic journalistic principles to help reporters and editors assess whether a story is ready for publication.

Clarity and accessibility

- Is the content presented in a structured manner?

- Is the language clear and free of jargon?

- Have the ideas been simplified to aid understanding?

- Does the story interpret the meaning and implications of figures?

Accuracy

- Does the story provide a complete picture (who, what, when, where, why)?

- Have all the facts in the story been verified and confirmed as correct?

Impartiality

- Does the story have background – a statement of the problem, issue or governance challenge?

- Does it show a global perspective or examples from other countries?

- Are different interests or perspectives represented in the story?

- Did people or entities mentioned in the story have an opportunity to comment?

Examples of good reporting practice

The examples given below can provide inspiration while preparing stories on exploration, establishing sound management systems for natural resources, and infrastructure challenges. Some highlight day-to-day reporting, while others are in-depth investigative reports. See previous section for useful criteria for assessing the strength of an extractives story.

-

Impact of new oil discovery in Guyana (investigative)

The $20 billion question for Guyana.

This long article by The New York Times discusses recent oil funds in Guyana to speculate about the country’s prospects of escaping the resource curse to see benefits from its newly discovered mineral riches.Descriptive language helps the reader travel with the reporter to Guyana’s capital, Georgetown, to explore local people’s hopes and fears in relation to the recent oil discovery there. The language also brings to life more technical aspects of the resource curse, while avoiding jargon. The journalist weaves relatable characters into his reporting, helping keep his readers attentive throughout the long text. He educates his readers to make sure they understand more theoretical concepts and can put figures and facts into perspective. By bringing in different voices and grounding speculations in historic facts, he depicts a balanced view of the situation.

-

Negotiations for new pipeline between Uganda and Tanzania (investigative)

Pipeline Dreams: Inside the Uganda-Tanzania Oil Pipeline Talks.

In this story the journalist from the Ugandan Daily Monitor explores the development of the midstream part of the production chain—pipelines. The writer gives a comprehensive overview of the history of the East African pipeline project and the current issues facing Uganda and its neighbor Tanzania as they move forward.With engaging language, the writer manages to be both educational and conversational. The structure of the article is easy to follow and sheds light on the various aspects of the pipeline negotiations, including financial models, geopolitical interests and the Ugandan government’s strategy for developing its oil sector. However, if some of the context had come earlier, the reader could better understand the story.

The journalist has worked making contacts in various parts of Uganda’s national oil company, and gets comment from the General Manager of the National Pipeline Company. Getting as many points of view as possible is critical in stories involving natural resources, especially with state-owned enterprises that often have a complex network of subsidiaries.

-

Behind the scenes of pipeline negotiations: Tips on story writing by Ugandan journalist Frederic Musisi.

Watch this video to hear Frederic Musisi, reporter for the Daily Monitor, explaining how he prepared for this four-part story on pipeline negotiations in March 2019: part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4.

Transcript

Full transcript

Q: Frederic, in March 2019, you published a series of four in-depth articles about the ongoing pipeline negotiations between Uganda and Tanzania. Could you summarize the issue for us?

The story was about ongoing negotiations for the proposed crude export pipeline and it’s called EACOP (East African Crude Oil Pipeline). If it eventually happens, it will be the longest heated pipeline in the world, from Uganda to Tanzania, where Uganda can then pick up its oil and take it straight to international markets. So the story tries to capture some of the themes that are ongoing. There are so many players involved, big players. As an original country, we are doing it for the first time, so really there’s a lot of giving and taking, and pulling and controlling. It was really an introductory piece, because for a very long time none had been written about the subject matter. So it’s one of those things that you pick up, spend about five months digging up, researching, talking to people. And I think it’s really a stepping-stone to subsequent reporting.Q: What were some of the first steps to get started?

What’s lucky for me is that I’ve written about this project right from inception. I had already covered it in phases, so definitely I have a grasp of some of the things and the developments that are related to that. What I thought was missing was that specific aspect of “How do they

negotiate this project again?” So the first [task] was to do a lot of researching. First, I structured it… because all the information can’t go in one piece. In this part of the world, we don’t do The New York Times kind of features where you have a 4000-word piece that covers the entire broadsheet. So, different to that, I had to break it down in parts for our audience.The first thing was to break down the parts that I at least know I want to do, and then embark on doing specific research on those areas. The reporting was going to take a lot of time, so it’s very precise that if I’m following a land issue, then definitely these are the sources I should turn to on land matters. If, it’s about environment-related issues…I should really be reading this and talking to sources around this. [If it’s about] local content, basically things to look out for and regard as local content: what has been done right? What is being proposed? And what could be covered? And looking at the experience before.

So, first I sketched out the story ideas I want to do, listed the sources that I potentially need, sources that I had that were going to be easy to get, sources that are not easy to get, and then from there I started picking out the missing links in each of the story ideas. I started out looking out for “I need to have…”, so that’s what really makes the reporting easy, when you do it that way, I think.

Q: Covering ongoing negotiations is particularly difficult because they are always wrapped in secrecy. How did you get around that?

It’s not entirely a direct answer, but…reporting in any specific field, you need to talk to people. [They] will give you information in varying degrees, given you’re in a rapport with them before. There are two types of information: things that they want you to know and things probably they think that you should know. Those are really two different things. So when I set out to do this and because I’d structured the stories in this way, I [asked] first, what was the commercial side of those negotiations? I need to know about this. I’m not a lawyer, so they’re already covering some of those things and it was easy, because I structured it in a way that it’s the commercial business I want to know about, so someone tells you they’re negotiating “abc,” so what’s happening with that? Even when some things are left hanging, you keep on asking those follow-up questions. So as opposed to saying, tell me about the negotiations—because that’s very broad, someone may certainly go “Oh make the other deal, we may get a deal”—you break it down in a way so you’re following certain specific points—either on land, on environment, on taxation, about revenue, things like that. So that really helped, and I have known some of these people for some time over the course of covering the sector, so I don’t think it was problematic getting them. Of course, they had that hesitation—they don’t think they should be sharing this, but still I managed to cajole them like you usually do with sources. You try to get the best out of them.Q: A cross-border piece comes with its own challenges. What were some of those challenges and what measures did you take to overcome them?

The first challenge is what’s appealing in Uganda is not necessarily appealing in Tanzania—these are two different settings. So it’s not like a prominent person has died, so that’s very appealing to everyone, right? You’re dealing with what Ugandans may want to know about the commercial aspects, definitely [in] Tanzania it’s different. So that was really the first challenge.

What I had to do is get all the information right from the field work, going along the road, talking to people. I even talked to Tanzanian people. I eventually went to Tanzania. I talked to the chief negotiator on the project. So then, after getting the information, when I sat down, that’s when I had to…segregate the information: this is relevant, this is not relevant, this is relevant for one audience…Then you can pick out what you can use where, for which part. Really that was I think the only challenge I faced. The other thing was…lucky for us… it’s an exciting project across the region and we are a syndicated organisation, so definitely the stories will be published in Tanzania for a Tanzanian audience, so I had to make sure that I [varied the content and talked about some of the social problems that are the same].Q: How did you manage to report on the Tanzanian side? What were some of the challenges there?

The trickiest part in Tanzania was your question all right… I think Tanzania is more bureaucratic, and I come from a background, Uganda, where I think it’s a free society actually. It’s one of the freest societies in Africa, where the journalists are open-minded, so some of the questions we asked or I asked Tanzanian people, they consider them either insensitive or inappropriate or basically that’s a no-go area for any ordinary person. But it doesn’t hurt to ask the question, so you ask the question and [people can choose] not to answer it or to give you a very vague answer. I mean at times, I’ve seen incidents where people fear to ask questions because they are pre-empting the other party and maybe they might not answer it right, and it happens quite a lot, but regardless just ask the question, approach the issues, and still I got the responses. I don’t think I’ve got everything I needed, but at least I got information that was specific to… the subject matter of the pipeline.

Sources

Several key tips can help journalists build a strong network of sources for covering the extractive sector. Informed and balanced reporting needs rigorous desk research and to include the perspectives of as many key players as possible.

Coronavirus disclaimer!

-

The oil, gas and mining circuit

Events

Companies and government agencies meet at regular industry events. Those include annual fora and conferences, sometimes hosted by a government to attract investors. These are excellent opportunities for interviews, networking and informal conversations to obtain background about certain situations and players. Reporters should contact the event’s media coordinators, ideally several weeks in advance, to secure press credentials. They can then try to set up meetings with representatives from the government, oil companies, subcontractors and trading companies.Leading annual regional and national events include:

- The Tanzania Oil and Gas International Trade Exhibition (“Expo”), which usually takes place in November and allows industry players to present the latest technology for oil and gas exploration. The Tanzania Oil and Gas Congress also brings together government players and investors every year, in October.

- The Uganda International Oil and Gas Summit gathers national and international stakeholders to share information about oil and gas exploration and production in Uganda.

- The Ghana Summit attracts stakeholders from across the country’s energy sector with a focus on oil, gas and LNG power generation.

- In Myanmar, the Oil and Gas Myanmar conference brings together key players from hydrocarbon companies and suppliers. The Myanmar Federation of Mining Association and the Myanmar Gems and Jewelry Entrepreneurs Association organize regular fairs at which journalists can also hope to develop valuable contacts.

- The Mining Indaba is held in Cape Town, South Africa, to promote investment in African mining. It brings together key investors, industry players and government officials, while the alternative mining indaba, which takes place simultaneously, offers a chance to meet with activists, local community representatives, academics and other members of civil society involved in campaigning around mining.

- Minexpo Kenya is a central event for stakeholders in the mining and processing of minerals in East Africa.

Key international events include:

- Every year in Denver, the United States, professionals from the oil and gas sector and investors gather at the Oil and Gas conference. This is a key event for companies to pitch to potential investors and it attracts many analysts.

- The Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada (PDAC) hosts an annual Mineral Exploration and Mining Convention in Toronto, where many investors meet.

- At the International Petroleum Week in London, United Kingdom, many oil and gas industry players gather to meet with environmental groups and other actors to discuss the future of the industry.

Industry Press

The industry press can help keep reporters informed of ongoing investment decisions, technological developments and relevant private-sector dynamics, such as company mergers or commodity price trends. Many outlets have a paywall, as with Energy Intelligence, one of the most widely read sources of business intelligence in the energy field. S&P Global Platts is a good alternative, as some of its analysis is available for free. Similarly, in the oil sector, rigzone.com offers cost-free access to news about exploration activities. For longer stories, the Oil & Gas journal and the Reuters feed offer valuable background knowledge. Argus is another useful source of information on energy and commodity markets, although many of its services require payment. -

Investigating company profiles

Company websites are good places to start when researching companies, as they often offer technical information as well as corporate statements on core policies and projects. Journalists can try to cross-reference information from company websites with OpenCorporates. It is the largest open company database in the world, with more than 185 million companies. All data come from public sources and are available for free. This database can provide helpful leads in terms of suggesting further research and new sources. Further cross-referencing with other data sources will be needed in order to establish whether there really is a tangible story to pursue.

It is usually not easy to make contact with companies directly to obtain quotes or further information. Journalists interested in pursuing regular reporting on oil, gas and mining should therefore take the time to build a network of contacts—for example by attending relevant industry events (see Events above). In the short-term, if individual companies do not reply to contact requests, industry associations such as a national chamber of mines can be useful sources.

-

Public institutions

The best starting place for reporters is the ministry or ministries (there might be several) in charge of leading government efforts to exploit natural resources. These tend to be ministries of energy, mines, hydrocarbon, petroleum or mineral resources. If the information provided on the ministry’s website is incomplete or outdated, journalists should contact its press office.

Oversight institutions such as parliament and supreme audit institutions are also important sources for reporters. These generally have a mandate to inform and scrutinize government action. They generate reports and hansards (verbatim reports of proceedings) that can serve as documentary sources for a story. Identifying relevant parliamentary committees and key parliamentarians is particularly helpful when new laws or amendments are being discussed.

-

Experts from civil society and academia

Experts from civil society and academia can be helpful commentators. They can often distance themselves from government or company interests, offering a different view of what is in the people’s interest. However, they can have biases, so it is important to get second or opposing opinions.

Civil society groups are also good sources of information. They can uncover cases of mismanagement through their investigations or highlight struggles of local communities impacted by extraction. Building a rapport with them and following them on social media can help journalists get tips for potential stories.

Where relevant, journalists are welcome to contact the NRGI country offices, where country staff can connect journalists with the right expert internally.

Other options for connecting with competent civil society or academic figures include:

- Publish What You Pay (PWYP), the global coalition of civil society organizations campaigning for a fair use of natural resources. PWYP has over 700 member organizations in 50 countries, working on numerous issues, including revenue management. Its national coordinators are able to direct journalists to a range of expert contacts.

- In EITI member countries, there will be civil society representatives on the national multi-stakeholder group. The national secretariat can also offer recommendations for civil society groups that specialize in licensing.

- Look up the profile of academic staff at universities. Relevant departments include geology, engineering, political science, economics, environmental studies, law and accounting.

There are also specialized organizations such as ProfNet or SciLine (Scientific Expertise and Context on Deadline) which help connect journalists with relevant experts, including beyond civil society and academia. Their services are free.

-

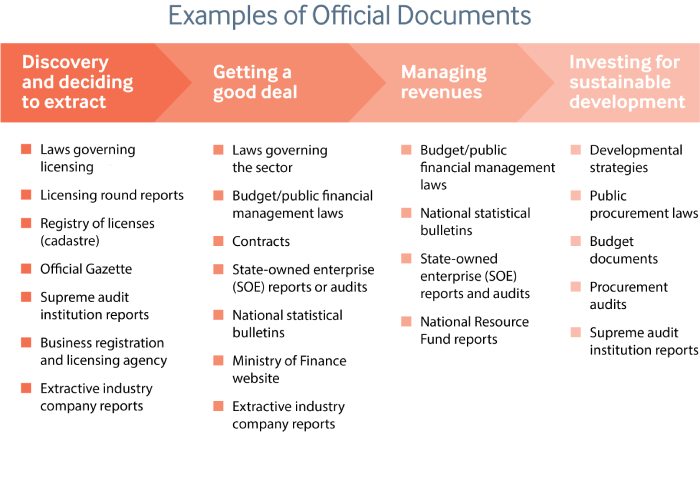

Using databases to inform natural resource reporting

ResourceData.org

NRGI maintains a database of documents relevant to the management of natural resources. It works as a repository of relevant documentation, including laws, reports by supreme audit institutions and national strategies, and of various datasets such as EITI data or financial statements by SOEs. Users can search for documents by country or by topic. These topics are based on the 12 precepts identified in the Natural Resource Charter, a governance framework for key decision points along the extractive value chain (see “Additional resources” below for more information). The table below shows types of official document available at resourcedata.org, useful for reporting on issues such as whether companies and state agencies are following the law.

List of official documents available on resourcedata.org (Source: NRGI) The Resource Governance Index

The Resource Governance Index (RGI) is a measure of transparency and accountability of the oil, gas and mining sectors in 81 resource-producing countries. The RGI gives countries an overall resource governance score by combining scores for three key components: value realization, revenue management and the enabling environment (see the framework below). The website allows users to explore country profiles and make comparisons between countries or between the oil and gas and mining sectors in some countries.Examples of how reporters have used the RGI in the past include:

- An article in The East African presents a regional analysis on the basis of the RGI ranking.

- A reporter from The Myanmar Insider using the RGI results for Myanmar to take a historical look at the development of the country’s extractive sector.

- A journalist at earthfinds.org using RGI findings for Uganda to give readers an overview of trends and challenges in the sector.

The RGI is a useful tool both for a quick overview of a country’s performance in governing the whole extractive sector, and for exploring the underlying data (such as relevant laws, SOE annual reports and press releases) for more detail.

Overview of what the RGI measures (Source: NRGI) Resource Watch

Resource Watch features hundreds of datasets on the state of the planet’s resources and citizens, including 84 related to energy and climate change. Users can visualize challenges facing people and the planet, from poverty to water risk, air pollution to human migration.Public energy data

To research how wider industry trends are likely to affect extraction in a country, journalists can explore several authoritative websites that publish country data, analysis or insights into trends in the market and the industry:- The US Energy Information Administration collects, analyzes and disseminates independent and impartial energy information through its website, to promote public understanding of energy and its interaction with the economy and the environment.

- Every year since 1952, British Petroleum has published an annual statistical review of world energy markets to inform industry trends.

- The OPEC website publishes information related to oil market developments, including supply and demand.

- The International Energy Agency (IEA) publishes global energy data, including on supply, consumption and prices. Various educational tools, such as training material and visualizations, make the information more accessible.

Voices

In the short videos below, the president of the Chamber of Mines in the Philippines, the CEO of the Ugandan national oil company and a member of the National Petroleum Authority in Ghana discuss the role that their respective institutions play in the extractive sector. A civil society representative from Myanmar also explains why it can sometimes be difficult to have a say in the governance of his country’s natural resources.

Learning resources

-

Key reports

The Natural Resource Charter provides a comprehensive framework for analyzing decisions about how a country manages its natural wealth. Its 12 steps (see below) follow the extractive value chain and offer norms and good practice for governments and societies to best harness opportunities created by mineral resources. For deeper analysis, the charter offers a detailed benchmarking framework that can help journalists prepare interviews with policymakers and propose policy reforms for the sector.

Overview of the Natural Resource Charter (Source:NRGI) In 2019, the International Monetary Fund issued the 4th pillar of its Fiscal Transparency Code, dedicated to the management of natural resources. This policy paper advises resource dependent countries on ensuring their management of natural resource revenues is transparent. It takes a comprehensive approach to the revenue management chain, from the ownership and allocation of resource rights, to resource revenue mobilization, budgeting and use. It can be a helpful diagnostic tool for journalists wanting to assess how well a country is doing in comparison to international good practice, and to highlight potential national-level transparency gaps and their consequences.

-

Other journalism guides to oil, gas and mining

The Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN) maintains a resources page specifically dedicated to covering the extractive industries, which lists relevant sources of information and advice on how to report on the sector.

The Thomson Reuters Foundation published a Reporter’s Guide to Oil and Gas in 2015, which provides very helpful advice to journalists wanting to cover hydrocarbon resources.

In 2019, the African Centre for Media Excellence released a Journalist’s Handbook to Reporting Mining. Beyond general reporting tips for journalists working on mining, it offers very targeted advice for the Ugandan context.

The Yangon Journalism School released a guide in Burmese to help journalists report on natural resources around election time, and beyond, in Myanmar. The guide is available on their Facebook page and can be viewed here.