Local winners and losers

Impacts on people and the environment

Download the full chapter in PDF

Why it matters

Why it matters to your audience

- Extractive projects have the potential to generate immediate benefits for local communities, through employment and the greater demand for goods and services.

- Companies spend more money on subcontracts and procurement than on paying taxes and royalties. A study of gold mining companies found that they spend USD 35 billion on payments to other businesses and less than USD 10 billion on royalty and tax payments to governments.

- Communities close to extraction projects suffer the direct consequences of extraction, such as loss of land, environmental degradation and health hazards. This is particularly true for women, who tend to bear more of the negative impacts of extraction, such as social and environmental costs, and are less likely to be able to participate in the local benefits, such as job opportunities.

- Environmental and social impacts can be significant, and may even be greater than government revenues. Studies on gold mining in Ghana, for example, have emphasized that losses in agricultural productivity from air pollution caused by mining in a particular year were larger than the fiscal revenues that gold projects generated for the nation in that year.

The basics

Oil, gas and mining projects can provide jobs and business opportunities, access to good roads, healthcare facilities, and other basic amenities for the communities hosting extractive activities. At the same time, extraction is often the source of major environmental and social disruption to those living around project sites.

Whether communities close to oil, gas and mining projects will win more than they lose is a complicated question, requiring perspectives from many different stakeholders. The national government is usually involved in setting the rules for negotiating with the company and deciding how or whether local communities should be involved. Local government officials are then in contact with extraction companies as representative leaders on issues, whether or not they represent all the people in the area. Different people may be impacted differently based on their gender, ethnicity and use of the land before the extraction starts. A company may be following the rules it was given, even if that results in some people being negatively impacted. Understanding these various perspectives is necessary for reporting on the local winners and losers.

-

Social and environmental risks of extraction

The environmental impact of oil, gas and mining projects

The environmental impacts of extractive activities are complex. They can affect different natural elements, such as water, air, soil, and biodiversity, and vary over the lifecycle of a project (see below). The types of impact depend on factors such as the geography and topography of the project, the technology necessary for extraction, the method of transportation required and the ways people used land before the project started.

Common risks in Mining

The process of taking a mineral out of the ground and separating it from the other minerals that are part of the same rock often creates a large amount of waste. Usually, more rock without value is extracted than rock that is going to be sold. Although there are technologies that can reduce this waste, they are often very expensive. Some of the most frequent types of environmental impacts from mining relate to the waste created, including:

- Water pollution and depletion

Water contamination happens when mining waste, often called tailings, ends up in waterways. Tailings are usually a mud-like substance made of ground-up rock left over after taking out the valuable mineral. Tailings often contain toxic minerals, which can make water unsafe for drinking, fishing, farming or swimming. Water can also be contaminated when the separation of rocks brings toxic substances to the surface that are carried into waterways by rain. Separating minerals and reducing the associated dust often requires large amounts of water, which can reduce the amount available for nearby communities. In water-scarce areas, this can result in significant impact on communities’ ability to maintain farming, forestry and cooking practices. - Air pollution

When rocks are crushed, some of the particles can be released into the air. If these are toxic minerals, the results can be very serious, increasing the likelihood of disease and health impacts for local people, particularly children. Even if the particles are non-toxic, such as dust, they can increase the likelihood of respiratory illness and damage crops. - Soil pollution and land degradation

Mining tends to have a large footprint on land, often making the area where extraction takes place and waste is stored unusable for long periods afterward. The moving of rock can also lead to erosion in other areas, particularly in open-pit and mountaintop removal mining. Other soil can be impacted through water and rain contamination. - Deforestation and loss of biodiversity

The land footprint of a mine can also directly reduce the forest and biodiversity that previously lived on that land. Changes in the noise, air quality and space for migration in the area can also impact the wildlife near an extraction project.

Risks across the lifecycle of a mine

The risks of environmental impact change during the lifecycle of a mine, from exploration to development, production and closure. Below are some of the potential environmental impacts throughout this lifecycle:- Exploration

As the company conducts surveys and seismic analysis and drills for samples, the risk of spills and contamination is low, but the process can cause noise disturbance and disrupt local wildlife. The impacts can increase during the exploration phase, as more heavy machinery is introduced and people who may have been environmental caretakers are targeted for resettlement. - Development

As a company prepares for production, it will build infrastructure, arrange resettlement and increase drilling or digging, which can generate noise and disturb habitat. The land footprint increases, as companies construct the mine and waste-holding areas. - Production

Field operations involve waste disposal, different forms of product processing, transportation and maintenance of infrastructure. These can increase the impact on the local ecosystem through erosion, noise, deforestation and water, air or ground contamination. - Closure

As the mine is closing, the company is responsible for securing waste, removing infrastructure and usually restoring the environment. Environmental impacts can be felt in the form of continued risks of spillage and contamination, and in difficulties, for the local flora and fauna to return to their previous habitat.

→ This short video provides an overview of environmental challenges in mining.

Common risks in oil and gas extraction

The types of environmental impact from oil and gas extraction differ from mining, because the technology used for extraction and transportation are different. The environmental impacts also change if there is on-shore or off-shore production, and depending on the type of extraction process used. Environmental risks for oil and gas extraction differ from mining in several ways:

- Flaring and Venting

Other gases are often released from the earth along with the desired oil and gas. These gases are often dealt with either by flaring or venting. Flaring, which is burning the gas, can have a large impact on air quality for communities and animals close to an extraction point. Venting, which is releasing the gas into the air, may also impact local air quality, but is also a major source of concern for its potential impact on Earth’s overall atmosphere and climate change. - Leaks and spills

In mining, the risk of contamination is often from less valuable rocks that are removed from the desired commodity. In oil extraction, there is risk of leakage and spill of the commodity itself. This can happen at the extraction point, as when the Deepwater Horizon oil well was poorly controlled and blew vast amounts of oil into the Gulf of Mexico. Spills and leaks can also take place during transportation, either through pipeline failures, as in Nigeria, or tanker failures, like the Exxon Valdez in Alaska. When oil leaks or spills into the environment, it can spread quickly, making the water unusable for drinking, fishing or farming, and significantly impacting local wildlife. - Climate impact

Many environmentalists are concerned about the impact of oil and gas extraction because of the potential use of the extracted product. When oil and gas are burned, they affect the atmosphere, increasing the risk of climate change. This environmental impact does not take place at the point of extraction, but is likely to impact the world more broadly.

The stages of oil and gas extraction each involve key risks:

- Exploration

The impacts of oil and gas exploration are often greater than of mining, as the drilling necessary after seismic testing requires more equipment. As a result, there is a greater land footprint earlier in an oil and gas project. - Development

As in mining, during the development phase, a company will be building additional infrastructure for drilling and transportation. For oil and gas, transportation often requires impacting a narrow pathway of land across a long distance for laying a pipeline. This phase often includes additional test drilling which can result in similar environmental impacts as production drilling. - Production

During production, there are local risks to water, air and soil, due to intentional or unintentional release of oil and gas. The land area of the extraction platform will also impact biodiversity. Some types of extraction processes, such as fracking, also involve risks of seismic activity during production. Risks of leaks or spillage during transportation are highest during the production phase. - Closure

Decommissioning of an oil project must include closing the well and removing machinery. The well must be carefully sealed so that the pressure beneath and above the closure is equal, ensuring oil does not continue to leak.

Social and cultural impacts of extraction

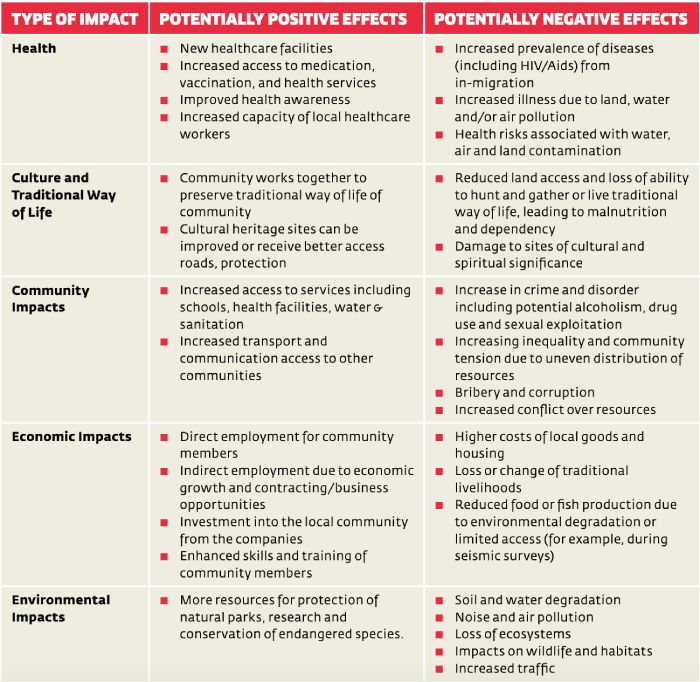

The social impacts of extraction include all the factors that affect people, whether directly or indirectly, on a day-to-day basis or over the longer term. This includes people’s way of life and their culture, community, political systems, environment, health and well-being, rights, livelihoods, fears and aspirations. The table below offers an overview of both potentially positive and negative social impacts relating to the extractive industry:

Social impacts of extraction (Source: Practical guide for local communities, civil society, and local government on the social aspects of oil, gas and mining, Cordaid, 2016) A positive impact for one community can have negative consequences for another. Inwards migration, which often results from expectations of economic gain, can support economic growth and educational opportunities in one situation, but result in rising levels of crime and drug use in another. Equally, experiences will vary across different population groups. Initial assessments of community impacts sometimes count only the impacts on certain types of people, such as men or people from a dominant ethnic group. The context of an extraction site can also exacerbate the social effects of a project. For instance, in an area where several extractive projects are located at the same time, the impacts of extraction can be cumulative.

Women in extractives: higher risks, lower rewards

Read more

Women experience the impact of extractive activities differently from men. Women tend to be more likely to experience social and environmental impacts because of differences in health risk and land use. Women have greater formal health needs through reproduction, and culturally tend to be carers within their families, so are more impacted by the health implications of extraction. Women carry out most of the agricultural work in traditional communities, and are responsible for fetching water and firewood, so face greater impacts if extraction disrupts these activities. Studies have shown that unless compensation is given in a gender-informed way, it tends to disproportionately benefit the men in the household, who may not incorporate the impacts on women into their decision making. In addition, women are less likely to benefit directly from jobs in the extractive sector. Studies have shown that women’s formal employment in the service sector may increase during an extraction period, but they are more likely than men to lose their work at the end of an extraction project.

At the same time, women have been an important source of protecting community interests in many extractive regions. They have often been at the front lines of protest against extraction companies involving civil disobedience, when the community believes it is not receiving a fair share of the benefits from extraction.→ For more detail on how to measure the gendered impact of extractives, see this Oxfam report on Gendered Impact Assessments. In addition, this report by Lahu Women’s Organisation describes the various consequences of platinum mining on women in Myanmar.

Land-related conflicts

Read more

To get natural resources out of the ground, extractive companies must have access to land above the ground for excavation and distribution operations. If the government does not already own the land, it often tries to gain ownership through a process of expropriation, known in some countries as “eminent domain.” Expropriation means the government seeks to become the owner of the land so that it can use it for the public good, in this case extracting natural resources. In other situations, even if the state does not expropriate the land, the government and extractive companies have mechanisms to oblige landowners to allow exploration or exploitation on their property. International law and most constitutions require the government to provide fair compensation to landowners if their land is going to be used partially or completely taken. This includes payment for the value of the land and for any improvements or structures on the land, and if there is resettlement, full restoration of livelihoods that addresses loss of connection to roads, income-generating activities and ancestral lands. This resettlement and compensation process is usually undertaken by government and company officials. When executed poorly, it can cause local anger and undermine the goodwill towards the company that helps it to operate. The process can be complicated when the government does not have clear documentation of land ownership, either because of weak tenure systems or poor impact assessments.→ This report by Resource Equity summarizes best practice in land management with mining.

Responding to environmental risks

The government has primary responsibility for overseeing companies’ management of environmental and social impacts. Before beginning licensing for an extraction area, governments often conduct strategic impact assessments (SIAs) that identify the potential social and environmental risks of extracting in the region. Governments also create standards of environmental protection and systems for anticipating, monitoring, reporting and responding to environmental impacts.

Documenting and planning for the risks

During the development or exploration phase of a project, companies are almost always asked by the government to conduct an environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA). These large documents record the company’s expectations about the social and environmental impacts of the project and how it plans to respond to those impacts. They typically include:- An assessment of direct, indirect and global risks from the project, in the short and long terms.

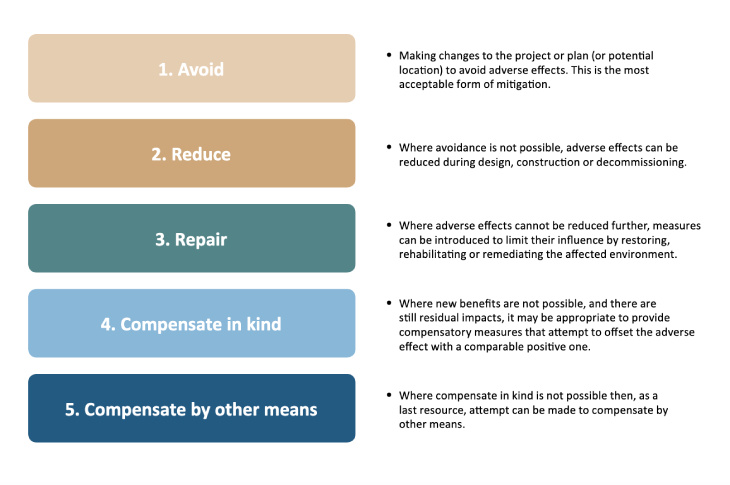

- A management and mitigation plan that includes how the company will avoid, reduce, repair or compensate for the impacts of extraction.

- The final project closure and decommissioning plan, including rehabilitation and reclamation of affected areas; decommissioning, removal and disposal of unwanted equipment and facilities; transfer of any useful assets (including company-owned housing, health or educational facilities) to local authorities or communities; post-closure site monitoring, if needed, and ensuring the continued viability of affected communities.

Governments usually need to approve this plan, but they do not all require companies to publish the ESIA.

Recommendations by the International Association for Impact Assessment (IAIA) on how to address adverse effects of projects. (Source: IAIA, Social Impact Assessment Guidance, 2016). Monitoring

Governments usually require companies to submit periodic reports that show their environmental impact and their efforts to respond to those impacts. Government agencies, usually the ministry of the environment, are responsible for reviewing and approving these reports. In addition, most governments have staff trained to independently monitor the environmental impact and the progress of the company’s mitigation plans. However, these monitoring teams are usually extremely under-resourced in relation to the number of extractive projects in a country. In many countries, civil society and the media are needed to provide oversight of government and company activities throughout the different stages of extraction.

Journalists tracking information released by governments and companies about environmental impacts can expect the following reporting at different stages of the extractive cycle:

Environmental reporting over lifecycle of a mine (Source: NRGI) → This video provides a brief overview of ESIAs, while this manual from the Environmental Law Alliance Worldwide gives steps for how to review an ESIA.

Engagement: consultation, community agreements and grievance mechanisms

In most countries, an extraction company negotiates and signs an agreement with the national government. When and whether the communities close to an extraction site are involved in discussions with the company depends on the context. Most companies have found that early and genuine engagement with communities improves the social goodwill needed for smooth operations and reduces the likelihood of disruption by angry communities.

Consultation

Consultation is how and whether the community near the extraction site is involved in discussions about the extraction project. Industry experts often refer to a spectrum of consultation, from a community being informed, to its members giving Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) for a project. FPIC is a way of engaging a community before extraction takes place, enabling its members to voice whether they believe the project should go ahead. FPIC is legally required by international law when companies work on land where there are indigenous people, but many companies have elected to use FPIC principles in all their projects. The image below summarizes some mining companies’ policies along the spectrum of consultation.

Overview of public commitments by mining companies to FPIC. (Source: Oxfam America, Community Consent Index, 2015) Some governments, like the Philippines, and international institutions, such as the World Bank and the International Finance Corporation, require companies working with them to engage in FPIC.

In practice, effective implementation of FPIC remains an ongoing challenge. Consultations are often too late for communities to really say no to a project or shape its development. There is also a significant imbalance of power and information between local communities and large extractive companies. This allows some companies to occasionally use superficial approaches or controversial influencing tactics, including bribery or political pressure, to persuade local leaders to support the project.

Community development agreements

In addition to the agreement between the company and the national government, companies are increasingly making agreements with the local community that seek to improve the welfare of people living near the project site. While such agreements are generally referred to as community development agreements (CDAs), there are many other terms used to describe them, including impact benefit agreements, benefit sharing agreements, indigenous land use agreements, cooperation agreements, social responsibility agreements and participation agreements. An example is the Social Responsibility Agreement set up between Newmont Ghana Gold Ltd and the Newmont Ahafo Development Foundation, which is run by a board of trustees and composed of company and community representatives. The beneficiaries are limited to the communities directly affected by the mine and located within the boundaries of the concession. The agreement set out that the foundation will receive revenue from the project, which can be applied towards programs for developing infrastructure and delivering other services. It also established an Agreement Forum, granted oversight responsibility for implementation of the agreement, and a Community Consultative Committee to manage information and communication between the company, the community and other stakeholders. Their remit includes developing programs for the closure and reclamation of the mine.CDAs are sometimes required by national law, as in Mongolia. Their key benefits include greater predictability for all parties on their respective obligations, improved mutual understanding via clearly defined shared responsibilities, and better development prospects as communities have the chance to shape their long-term development goals. However, as with all agreements, CDAs do not always have their intended results. Insufficient flexibility or poor consultation can undermine the usefulness or practicality of these agreements. Poor design of CDAs can result in duplication of existing local and regional initiatives, or in interest groups who are not part of the community (such as migrant workers) being overlooked. Key factors for success include effective consultation with communities, including women and marginalized members, when designing and agreeing community development plans. Coordination with local and national government, as applicable, and participation of the community in monitoring implementation is also important.

→ Columbia University and the community legal empowerment group Namati have collaborated to create a guide for communities negotiating investments. This includes a plain-language overview of the CDA process.

Grievance mechanisms

A grievance mechanism is a way for community members to raise concerns about an ongoing extraction project or related issues. Sometimes these concerns are sent to the company and sometimes to different government authorities. Companies often benefit from legitimate grievance mechanisms as a way to avoid problems before they escalate. The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights have created criteria to help companies understand whether a grievance mechanism will be effective in protecting human rights. These criteria include being legitimate, accessible, predictable, equitable, transparent, rights-compatible, a source of continuous learning and based on engagement and dialogue.→ The International Council on Mining and Metals has a toolkit for companies creating grievance mechanisms that goes through the steps required to be effective.

- Water pollution and depletion

-

Using “local content” to ensure benefits to the local economy

“Local content” is the value that an extraction project brings to the local, regional or national economy, beyond the revenues from extracted resources. A leading area of local content is the employment that the natural resource discovery generates, whether direct, indirect or induced (jobs in industries that interact with the natural resource economy, such as transportation or accounting). Businesses, goods and services, capital and infrastructure are further non-tax benefits that can be accrued from extractive projects. Countries can encourage local content through requirements and targets written into national laws and individual contracts.

Developing a local content policy

To encourage local content, governments often create requirements for extractive companies to include local labor, products or companies. They use a variety of tools to reach their goal of benefiting the local economy through the extraction project, including:- Quotas: Found within laws, regulations or contracts, these are provisions that require companies to award a certain percentage of hires, contracts or equity ownership to local companies or professionals.

- Training program requirements or incentives: These require or encourage companies to build skills among the domestic workforce.

- Public education initiatives: Through these, the state or the company opens training centers, establishes programs or organizes overseas scholarships to build a cadre of expertise in sectors with strategic links to oil and minerals.

- Incentives for small business development: Such incentives can include fostering better access to credit for small business owners or opening business incubation centers. This can be done by the government or the company.

- Processing and production of derivative products: This includes refining crude oil or smelting minerals, which can capture significant economic benefits if carried out domestically, but also can be expensive and complicated to construct.

Overcoming technical barriers and limiting corruption when implementing local content

The technical requirements of the extractive industry can make producing strong results around local content very difficult. For example, Tanzania has some experienced welders, but when BG, a British multinational oil and gas company, was looking for welders to help with the construction of its large offshore gas platform, it found few who could weld the specific types of piping necessary for the job. Existing welders required advanced training to be able to meet the needs of the company. This is why local content rules are often flexible enough to allow companies to use human or other resources from outside the host country if labor or service needs cannot be met locally.

Corruption is the other important obstacle to ensuring that local content policies deliver tangible benefits to citizens and local communities. Rules that require local suppliers or that equity ownership goes to local companies can be a backdoor for the corrupt plans of those pretending to create local companies to profit from the law. Requirements that governments partner with local companies can lead politicians, business elites, and PEPs (politically exposed people) to hide behind “local” shell companies. Open and transparent procurement procedures are essential to prevent this opportunity for corruption.

Governments face a question about the benefit or sustainability of investing in local content, making it a controversial policy tool. Because extractive resources are finite, it can be detrimental to create more economic focus on the extractive industries. Some development specialists suggest creating a broader economy by using local content provisions to develop a workforce with skills that can be transferred to other sectors once extraction projects are over.

Extractive-linked infrastructure

Read more

Natural resource companies need large infrastructure systems for water, power and telecommunications to serve their extraction sites. They also need pipelines, ports and railways to get resources to market. These projects are called extractive-linked infrastructure.

The infrastructure that serves citizens, as well as the extraction site, is called shared-use infrastructure. For example, natural resource companies can build water or power infrastructure that can also be used by the community living near the extraction site.

In contrast, enclave infrastructure is when mining or oil and gas companies have built a parallel system of development that serves the needs of the extractive company, but not the local community. In Sierra Leone, for example, mines included their own power-generating systems without linking to the national electric grid or sharing power with local communities.

Enclaves can make sense from an investor’s perspective, as it is often difficult for companies to coordinate sharing the costs and use of infrastructure. Some companies can see a competitive advantage when they are the sole operator of infrastructure, as this allows them to better market themselves to the government to win future concessions in the area. For example, sole use of a railway, without all the coordination necessary when sharing such a system, can help prevent delays at a port.

However, enclave infrastructure projects can be risky for governments. Enclaves can increase the possibility of stranded assets—“ghost” infrastructure projects that sit unused and serve no purpose following the final phase of an extraction project.→ The NRGI primer on this issue offers further reading. For greater detail, consult the list of resources put together by the Columbia Center for Sustainable Development.

Story leads

Research questions and reporting angles

Below are story angles for reporting on the local impacts of extraction, based on a sequence of research questions. See Chapter 1 for more general story planning guidelines.

Some of the story leads in other chapters can also be useful for covering local impacts:

- Chapter 2, story lead D. on consultation

- Chapter 4, story lead B. on monitoring revenue collection

- Chapter 5, story lead D. on monitoring whether revenue transfers are received subnationally.

-

A. Who is getting jobs from the extraction site?

1. Find out the rules. The rules for who should be hired for the project will come from both the law and the contract for this project. Usually, the contract will note when there are references to national law.

- Look for the legal framework. Possible sources include:

- Resourcedata.org. This is a repository of documents relevant to resource governance, including legislation from many countries. Documents can be filtered by country and by the individual precept of the Natural Resource Charter, a governance framework that covers the whole decision chain. Precepts relevant to finding the terms of the agreement include Precepts 10 (private-sector development) and 5 (local effects).

- EITI. The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) requires member countries to describe the legal framework, including references to local content. Reports are published on an annual basis with a time-lag of 1–2 years and can be found on the international EITI website or national pages.

- Look for the contract itself. Possible sources include:

- Resourcecontracts.org. This is an online repository of publicly available oil, gas and mining contracts.

- Government sources. Many countries publish contracts they sign with extractive companies on ministry websites or through a dedicated portal. In some cases, the online cadastre system will list the terms associated with each license. EITI implementing countries will have to publish all contracts from 2021.

- Company websites. Some companies, such as Total, Tullow Oil and Rio Tinto, have committed to making contracts publicly available, provided their government counterpart has no objection. Other listed companies may publish selected terms of contracts, in particular fiscal terms, to their investors. These may be available in regulatory filings in the relevant stock exchanges or company websites.

2. Investigate expectations. Expectations for employment in extraction projects are often extremely high and may have little correlation to the formal rules. Understanding these expectations, and where they may have come from, is important for understanding community and government responses later in the project.

- Consult the community. Interview different types of people from communities near the extraction site about their expectations of who would be employed by this project. Including men, women, leaders and minorities can help balance reporting. To understand what sources are most credible in the community, it is important to ask why people had certain expectations.

- Consult the government. Interviewing national and local government officials about their expectations of how many people, from where, would be employed by the project can also help show how realistic the legal framework is. Asking the basis for their assumptions can help explain their policy decisions.

- Consult the industry. Interviewing the extractive company and peer companies about their expectations for employment can help draw out what challenges may have emerged once extraction started. For example, a company may have intended to hire local personnel as welders, but had trouble finding people with the right experience, or the welders may be needed sooner than the time it takes to train individuals.

3. Find employment figures. Different sources can show how many people are being employed, with varying levels of detail:

- Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). EITI-implementing countries are required to disclose figures for how many people are employed, including from the country of the extraction site, broken down by gender. Some countries also publish the information broken down by those who live near the extraction site, compared with those of the nation overall.

- Company sources. Public companies often report employment figures to investors or make corporate filings. U.K.-registered companies must report the gender breakdown of their employees. These figures do not always reveal whether employees are of national or foreign origin, and they rarely show which part of a country the employees come from (e.g., close to a project site). Searching the OpenCorporates database should reveal corporate stock exchange filings, while reviewing the company website may reveal informal reports. Private and state-owned companies often have different reporting requirements and may not make this information available.

- Government sources. In some countries, sectoral ministries or ministries of labor publish figures annually about national employment rates at various projects. This is particularly true if there is a strong local content component to the national strategy for benefiting from extractives. Even if these figures are not published proactively, interviewing ministry officials should reveal the level of employment at different sites. If this still is not available and there is a freedom of information law, consider making a formal request for the national tracking of the employment figures.

4. Explore gaps between obligations, expectations, and actual numbers. If the information shows that the company is not meeting its obligations, it is worth investigating:

- The labor supply. Asking ministry and industry officials why there is a gap may reveal a mismatch in needed skills. Are any training programs run by the government or industry to resolve this over time? It is also useful to understand the realistic timeframe for education for these roles and whether this is feasible during the timeframe of the planned extraction.

- The hiring process. It is important to understand where and how a company is seeking to fill roles and what it is doing to include nationals. Are there types of job that are hardest for it to fill? What types of skill are most needed?

- Local reactions. It is useful to ask the people who live closest to the extraction site—both leaders and the general population—about who is getting jobs in the industry and how this happens. Do their stories match up with what the industry and national government are saying? If not, what are the gaps?

- Look for the legal framework. Possible sources include:

-

B. Are there signs that the environmental impact is different than expected?

1. Understand expectations. Taking minerals out of the ground is going to have an environmental impact because it requires a change to the environment. There are often very different expectations for what that impact will mean, and different understandings across stakeholders of what is “normal.” Understanding the starting point for people’s expectations can lead to a balanced inquiry into whether the current situation is cause for alarm.

- Informal expectations

- Consult the community. Interview different types of people from the community close to the extraction site about their expectations of how the environment would be impacted, in what timeframe. Including men, women, leaders and minorities can help balance reporting. To understand what sources are most credible in the community and what information people were given during the consultation process, ask why they have certain expectations.

- Consult the government. Interviewing national and local government officials about their expectations of the types and timing of environmental impact can also reveal how realistic their mitigation plans might be. Asking them the basis for their assumptions can help explain their policy decisions.

- Consult the industry. Interviewing the extraction company and peer companies about their expectations of environmental impact can help uncover unexpected challenges that may have emerged once extraction started.

- Formal expectations

- Environmental and Social Impact Assessments (ESIAs) (or their summary). These are very lengthy documents that describe the company’s expected social and environmental impacts and how it plans to address any issues. They are usually formally submitted to the government for approval. Because these are very long, it can be useful to refer to their executive summaries or company press releases that summarize the key findings—but note that the company has an interest in minimizing the impacts in the summary. If the document is daunting, it is also possible just to read about the particular types of environmental impacts currently causing concern. These reports may be found via:

- Company release. Companies often need to release this information to attract investors. Some stock exchanges ask for it as part of a technical report (e.g., the NI 43-101 on the Toronto Stock Exchange). Stock exchange websites can show such reports as part of their filings. Company websites are also useful, as even smaller companies may release this information to show the feasibility of a project.

- Government disclosure or review. Some governments post environmental impact assessments once they have been reviewed. If they are not publicly available, government officials from the ministry of the environment or the sectoral ministry may have access to the document. Governments often make a statement of approval for an ESIA that may include summary information.

- International financial institutions. Some international financial institutions, like the International Finance Corporation, require transparency of the ESIA. Such institutions usually have a searchable database on their website containing ESIAs.

- Consulting experts. Expert consultations can be invaluable when considering environmental impacts. Interviewing both civil society and industry experts about the types of environmental impact from certain mineral extraction techniques can provide context to the expectations for a particular project. They can also help define terms and raise questions that should be answered for a project.

- Environmental and Social Impact Assessments (ESIAs) (or their summary). These are very lengthy documents that describe the company’s expected social and environmental impacts and how it plans to address any issues. They are usually formally submitted to the government for approval. Because these are very long, it can be useful to refer to their executive summaries or company press releases that summarize the key findings—but note that the company has an interest in minimizing the impacts in the summary. If the document is daunting, it is also possible just to read about the particular types of environmental impacts currently causing concern. These reports may be found via:

2. Understand signs of impact. Investigating perspectives on the actual impact can be a daunting task, often requiring advanced degrees in environmental science. Reporters can highlight areas for further inquiry through:

- Formal monitoring. Companies usually submit to governments periodic reports on their observations of environmental impact, with the reporting period likely to be in the contract. However, companies tend to have an interest in characterizing impacts as minimal. Government agencies usually review and approve these reports, with many governments legally obliged to independently assess the environmental impact—even though they may lack the resources needed. These reports can be useful, but if there is not time to review them entirely, asking government officials about their assessment of company monitoring to date can provide information on corporate and government perspectives.

- Informal monitoring. Reporters do not need to conduct monitoring directly. Instead, they can relay different perspectives on the current impact. Consider interviewing the following:

- The community. Interview different types of people from the community close to the extraction site about their experience of the environmental impacts of extraction. Include men, women, leaders, and minorities to help balance reporting. Often it may help to narrow reporting to one type of environmental impact (such as soil, water or air), as different members of the community may be impacted in different ways. Encourage community members to be specific about the timing and extent of the impact, and ask them how they know that this is different from before the extraction (especially in cases of less visible impacts). This helps establish the credibility of your sources.

- The government. Interview national and local government officials about their understanding of the types and timing of environmental impact, to uncover their awareness of the situation.

- The industry. Interviewing the extraction company and peer companies about their understanding of environmental impact is an important factor in balanced reporting. Asking them to comment on whether this differs from their expectations can provide perspective on the situation.

- Civil society monitoring. In some cases, civil society organizations conduct their own monitoring of the impacts of extractive projects. This can range in technical expertise from counting the number of trucks on a road to analyzing soil samples. Reviewing civil society reports can reveal the extent of the impact. These reports can also be used to further interviews with other stakeholders.

3. Consider implications. During day-to-day investigations, reporters are unlikely to be able to carry out a complete technical analysis that compares the initial impact assessment to current environmental impacts. However, by giving space for different perspectives, reporters can follow some helpful story angles:

- Do experiences differ from expectations? There may be a newsworthy story if experiences differ significantly from expectations, either across stakeholders or across the timeframe. Asking industry and government officials to respond to these differences is essential to providing a credible, balanced report. This angle may also reveal something about what the local community heard about extraction and how they were involved in consultation, instead of just being about the actual impact.

- Has this occurred before? If expectations are not being met, it is often helpful to understand whether this type of impact has happened at other extraction sites in the country or managed by this company. Civil society groups specialized in this sector can offer useful perspective on this.

- What are the company and government plans for next steps? Even if the impacts do not match expectations, there may be expectations that the impacts will be addressed. It can be helpful for audiences to know the next steps to expect from company and government officials. This may also be a time to report on whether grievance mechanisms exist and how they can be used.

- Informal expectations

Examples of good reporting practice

The examples given below can provide inspiration while preparing stories on local social, economic and environmental impacts. Some highlight day-to-day reporting, while others are in-depth investigative reports.

-

Social and environmental impacts of mining in Myanmar (investigative)

The Wild West: Gold Mining and its Hazards in Myanmar

This four-part multimedia investigation by Radio Free Asia contrasts the high expectations for wealth from gold mining with the social and environmental impacts in the communities closest to extraction in Myanmar’s Kachin State. The articles successfully provide specific details that show development as a result of mining, such as newly paved roads, alongside environmental impacts, such as destroyed farmland and shrinking lakes. The reporters describe in detail the impacts on culture, workers and the community, and show how the government’s licensing rules have allowed these impacts to increase unchecked in recent years. The articles make good use of visualization, such as an interactive map, while a combination of photos, video and thematic stories make the investigation feel comprehensive. It mentions the government view, but would be stronger if it directly sought comment from government officials. This story and others like it influenced lawmakers in Myanmar to make reforms to the small-scale mining sector. -

Missing local content expectations (day-to-day)

Ghana won’t meet target for local content quota in oil and gas sector

This article by Ghana Business News, a national business newspaper, explains that Ghana will not meet local content expectations and gives reasons why. It uses the 10-year anniversary of the setting of local content goals as a hook into this investigation. The author successfully links figures for Ghana’s performance and expectations with quotes from government, industry and civil society actors to explain reasons for the gap—including very frank insights from government officials across several ministries. As the article is written for a business audience, it uses industry jargon and refers to ongoing extractive projects without specific background. To find out more, the reporter could ask what trade-offs the government has made with companies resulting in these unfulfilled promises. -

Controversial approval of ESIA in Uganda (day-to-day)

Total E&P project approved

This article in the Ugandan daily newspaper, The Independent, does a good job of using a project event—the approval of an ESIA report—to provide readers with different perspectives on the potential impact of an oil project. The reporter interviewed a variety of actors, including from government, civil society, industry specialists and companies, to show different perspectives. In addition to discussing potential environmental impacts, the article also describes the EIA process and the number of local community members involved. These details about process give readers perspective on different viewpoints. The research process is described below. -

Behind the scenes of environmental reporting: Tips from Ugandan reporter Ronald Musoke

Ronald has been a journalist for 11 years and started covering the extractive sector in 2012 after completing a six-month fellowship at the African Centre for Media Excellence on oil, gas and mining reporting. He is now working for the weekly magazine The Independent. The advice he shares here relates to a story (see above) he wrote about the sensitive environmental impact assessment for a major infrastructure project needed to commercialize Ugandan oil and currently being developed in a fragile ecosystem, the Murchison Falls National Park.

1. How did you develop the story idea?

Two contradictory statements about the approval process of the environmental safeguards plans for the project sparked my interest. The first statement was published by the leading private company on this project, the oil major Total, praising the National Environment Management Agency (NEMA) for having approved the project. The second one came from a reputable environmental NGO expressing concerns that the approval had gone ahead without taking into consideration local communities’ concerns. I wanted to follow up and started reading about the process, including preparations for the public hearings that were organized by NEMA to consult on Total’s environmental impact assessment. This initial research convinced me that I had a good story and I pitched it to my editor who told me to go ahead and write the story.2. How did you then build your story?

I continued my research by gathering further material about the project from the NEMA website. My advice on how to sift through bulky reports under time constraint is to go for the executive summary and to scan the document for particular themes to quicken your search. I then contacted key sources that could comment on the process and give my story more credibility and balance in voices. Those included AFIEGO (the African Institute for Energy Governance), a think-tank that follows oil and gas issues in Uganda, someone at the Uganda Wildlife Authority, an official at the Uganda Ministry for Tourism, and an independent expert who has experience working on environmental aspects for oil projects around the world. Once I had gotten hold of all those elements, I started writing.

The story was built around the question of whether the government—once it had made the decision to extract oil in this fragile area—was following all the required steps and adhering to the law of the country. My research had shown that some of those steps had been sidestepped in pursuit of the oil promise and that’s what I tried to tell in my article. It is our role as journalists to keep the authorities on their toes.3. Environmental reporting can be technical and therefore challenging to communicate to a wider audience. What is your advice to others?

The first step towards communicating complex content is making sure you understand it well yourself. Having trained in environmental reporting has been a great help in that regard. The second is to visualize the audience you are trying to address, and in my case, I try to aim for a high-school graduate. That means avoiding jargon and translating technical terms into simple language. One trick is to ask an expert to explain the issue to you so that you can relay it in an accessible way to your audience, without oversimplifying. Working closely with your editor is also very important, as he or she will help flag language that needs further clarification and assist you in making sure the story is relevant to your audience.4. One thing that would have made your report even better?

Going to the field would have given the story more texture. Reporting with your senses makes a story more vivid for your audience.

Sources

Below are sources that can contribute to different angles on stories about local impacts. Some will be similar across different aspects of mining, oil and gas reporting, and are repeated across chapters, but others apply specifically to local impacts. When possible, there are direct links to institutions in the main target countries of “Covering Extractives”: Ghana, Myanmar, Tanzania and Uganda.

Coronavirus disclaimer!

-

Local stakeholders

If a story is about local impacts, it is important to speak to people, including women, from affected communities. Laborers at the mining or oil exploration project site, community-level workers’ associations, security guards, farmers and traditional chiefs are not only important human sources, but can also help reporters build convincing characters for storytelling. Where a Community Development Agreement has been signed, it is useful to speak to the community representatives involved in approving the agreement.

As with all sources, community claims need to be verified—for example, against corresponding perspectives from experts (see below), official documentation, and ideally against reactions from public authorities and the company operating in that area. Reporting is particularly valuable when it includes voices that represent a diversity of views, including women and ethnic minorities, who may have different experiences of extraction.

-

Public institutions

Government bodies

At local level, various local authorities—the mayor, municipal employees, or governor of the extractive province—can provide information about the role of local government and recent impacts on the community. There are often multiple layers of local government with commitments from the extractive company or responsibilities for monitoring community impacts. Similarly, parliamentarians representing the area tend to have insights on community relations with the extraction company and the impacts people are facing.At central government level, a range of agencies is involved in making commitments about the local impacts of extraction and monitoring these. In addition to the ministry for mining or petroleum, the following can be involved:

- Environmental and conservation ministries often set standards for environmental safeguards and oversee the monitoring of company compliance. Officials in these ministries may also be able to give perspective on how the extractive industries are viewed in comparison to other industries.

- While the environmental ministry is usually in charge of assessing whether there is contamination, officials in the ministry of health may be able to comment on the implications of environmental impacts. They also sometimes set rules related to certain types of health impacts.

- In countries where human rights are at issue in relation to extraction, a national commission on human rights or government focal point on minorities, such as indigenous affairs, may offer valuable information. Staff from these ministries may not have expertise on extractives, but could provide commentary on how a country usually responds to human rights violations.

- Issues of local content are usually guided by the petroleum or mining ministry, but may also involve collaboration with the ministries of the economy or education. In countries with strong gender-balancing incentives, such as Uganda, the ministry of gender also has a role in ensuring balanced local content.

Oversight institutions

In many countries, parliament reviews how extraction sites are monitored for environmental and social impacts, through parliamentary hearings. Through their legislative powers, parliaments often set the rules for what is acceptable in terms of environmental and social impacts. Parliamentarians from an extractive country may be able to say whether the standard process is moving forward.

Other agencies, such as supreme audit institutions, can also have a role in monitoring local impacts or the ministries responsible. For example, the Office of the Auditor-General in Uganda conducted an audit of the national environmental agency, reviewing the agency’s ability to monitor waste management in the new oil-producing region. The same auditor went on to review the implementation of a local content plan. Auditors may also be able to uncover areas in the subcontracting process that could be open to corruption or other risks.

-

The private sector

Contacting companies involved in the extraction project can be important to ensuring balanced reporting on an issue of concern. Reporters can contact a company’s national office, which may give information on a specific project, or its international headquarters, which can provide context about a company’s good practice in terms of social and environmental impacts. Companies often release information about their social and environmental impact mitigation plans on their websites to attract or reassure investors.

Industry groups, such as a chamber of mines or petroleum, can offer a national industry perspective on good practice related to local impacts. They can also suggest contacts who have been involved in coordinating local content and industry. Interviewing some subcontractors about the process of becoming engaged in the project can also provide another perspective for balanced reporting.

-

Experts, civil society and watchdogs

National groups

Experts from civil society and academia can be helpful commentators on local impacts. They can distance themselves from government or company interests, and offer a different view and analysis of what is in the people’s interest. They can also connect reporters with individuals or groups who are impacted by a certain issue.Where relevant, journalists are welcome to contact the NRGI country offices, where staff can provide connections with the right expert internally.

Other options for connecting with competent civil society or academic figures include:

- Publish What You Pay (PWYP), the global coalition of civil society organizations campaigning for a fair use of natural resources. PWYP has over 700 member organizations in 50 countries, working on numerous issues, including local impacts. Its national coordinators are able to direct journalists to a range of expert contacts.

- In EITI member countries, there will be civil society representatives on the national multi-stakeholder group. The national secretariat can also offer recommendations for civil society groups that specialize in local impacts.

International civil society

International policy groups and research institutes produce valuable research on good practices related to the social and environmental impacts of extraction. Some, such as the Environmental Law Alliance Worldwide, specialize in particular impacts. Others, like the Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals, and Sustainable Development, focus on impacts from the extractive industries. -

International institutions

International financial institutions

The World Bank Group, including the International Finance Corporation, and regional development banks (such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development) have written standards for how to monitor the social and environmental impacts of projects they fund. They also have strict criteria for consultation processes at the beginning of a project. Reporters can contact the individuals responsible for lending on a specific project and ask about the process of monitoring the impacts of that project, and progress being made. Country or issue specialists from these institutions can also provide reporters with background on the institution’s usual practice for ensuring compliance and how it responds when companies fail to meet goals.Other international institutions, like the United Nations Environment Program, frequently produce relevant analysis and guidance to preventing, measuring and mitigating social and environmental impacts of the extractive industries.

Multi-stakeholder initiatives

The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) is a multi-stakeholder initiative that supports transparency in resource-rich countries through an international standard implemented by members. EITI-implementing countries are required to annually disclose significant information about local impacts, including spending related to environmental impacts, local labor figures broken down by gender, and the process for subcontracting procurement. Although EITI data is often published slowly, the descriptive reports and the types of information available can be used as a basis for questions to ministries for more current stories. The national multi-stakeholder group that oversees a country’s EITI process can also be a source for discussions on what information about local impacts should be publicly available.The Open Government Partnership (OGP) is an international multi-stakeholder initiative that supports countries in processes of transparency and accountability. Multi-stakeholder groups within countries that have signed up to the initiative set national goals for openness in sectors they prioritize. An OGP goal in recent years has been to promote inclusion of the voices of minorities, including women, indigenous people and people from rural areas. As a result, OGP national groups may be able to provide information on local impacts.

-

Data sources

There are several useful data sources for covering the impacts of natural resource projects on local communities.

Repositories of environmental impact assessment laws

The Environmental Law Alliance Worldwide is a global alliance of attorneys, scientists and other advocates which helps communities protect their environment, with an online repository of Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) laws and regulations. The Netherlands Commission for Environmental Assessment has a similar online repository of EIA and Strategic Environmental Assessment legal frameworks.Social impacts

The Responsible Mining Index measures whether and how the biggest 30 mining companies contribute to the economy and local communities near mining extraction sites. Its Document Library hosts a wealth of corporate documents that can be scanned by company.

The University of Queensland’s Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining has launched a database of displacement and resettlement due to mining. Records are structured around “events” rather than “mining projects,” on the basis that a mining project will often undertake, or cause, several displacements during its lifecycle. In this dataset, each instance of displacement is treated as an “event.”

Similarly, the Institute for Environmental Science and Technology at the Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona maintains an Environmental Justice Atlas to document ongoing social conflicts around environmental issues. It can help journalists identify and keep track of community struggles to defend their land, air, water, forests against extractive activities in particular. The database contains information on the investors, the drivers for these deals, and their impacts, basic data, source of conflict, project details, conflict and mobilization, impacts, outcome, references to legislation, academic research, videos and pictures.

In collaboration with the Canadian International Resources and Development Institute, the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment keeps track of publicly available community development agreements through its online repository, which can be scanned by country, company, resource or agreement type.Repository of local content legal frameworks

The Columbia Center on Sustainable Environment hosts a repository of local content laws and contractual provisions, which can be scanned through its country profiles.

Voices

To help reporters gain perspective on the local impacts of extractive projects, civil society representatives from Senegal and Guyana, members of the Ghanaian and Filipino Chambers of Mines, and an expert from the Norwegian supreme audit institution share their views in the videos below.

Learning resources

-

Video overviews

This two-minute video from UNU-WIDER gives an overview of the challenge of balancing social and environmental impacts against potential long-term benefits from extraction. In this slightly longer video, Daniel Franks of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) discusses the potential environmental implications of oil and gas extraction and social dangers from mining.

This 12-minute video is a strong overview of local content by Anthony Paul from the Association of Caribbean Energy Specialists. He begins by explaining how his native Trinidad and Tobago was able to take advantage of extraction companies to train local communities and improve education, and then discusses the broader local content principles.

-

Key reports

To understand social and environmental impacts, the following three reports are leading resources:

- A guidance book by Environmental Law Alliance Worldwide (ELAW) gives very detailed steps about how to read and follow up on an environmental impact assessment.

- UNDP created an extensive review of good practice across steps of extraction in its report, Extracting Good Practice. Reporters can look at chapters relevant to the phase of extraction for a particular mining project.

- Oxfam Australia created a guidance note on how to conduct Gendered Impact Assessments which include views from across genders.

For understanding local content issues, NRGI has created a short primer that gives a plain-language overview of the topic. In addition, key resources include:

- The World Bank’s five-chapter report about key local content issues in the oil and gas sector. The last chapter profiles examples from Angola, Brazil, Kazakhstan, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Trinidad and Tobago.

- The Local Procurement Reporting Mechanism (LPRM), a disclosure tool developed by the “Mining Shared Value” initiative of Engineers Without Borders Canada in 2017. It aims to standardize how the global mining industry and host countries measure and talk about local procurement.

- In its report about extractive industries suppliers, NRGI looks at the economic significance of suppliers and the governance risks that arise from their currently weak oversight.

Community Development Agreements are an increasingly researched area. The following resources can be helpful in reporting:

- Namati worked with Columbia University to create a two-part guide for communities on how to prepare for and negotiate community development agreements.

- The International Council on Mining and Minerals created a toolkit for mining companies on how to engage with communities and incorporate stakeholder perspectives into their agreements.

- Many researchers have reviewed recent CDAs to learn about good practice. Usually, these reports are country specific, like this one by the Canadian International Resources Development Institute in Ghana and this review by NRGI in Mongolia.