Licensing

Getting access to resources

Download the full chapter in PDF

Why it matters

Why does this matter to your audience?

- Deals in oil, gas and mining sectors are often worth billions of dollars and last for generations.

- Licensing processes usually take place in a country’s capital, before big equipment or excavation would be noticed locally. That means the deal is often signed before the people who are going to be most impacted know what is happening.

- Licensing is the process of deciding which company gets the extractive deal, and the terms of that deal. It is the moment in the cycle of an extractive process with the highest risk of corruption. Corruption in making the deal means a country could be tied to a bad deal or a bad actor for decades. This increases the risk of lower revenues, fewer employment opportunities, fewer links with local businesses, and greater social and environmental impact.

- Potential losses are huge. The Democratic Republic of the Congo lost USD 1.36 billion in public revenues between 2010 and 2012 from underpriced sales of state mining stakes. This figure is twice the country’s combined health and education budgets for one year.

- If licensing processes are transparent, people have a better chance of catching problems early.

The basics

In most countries, the state owns all minerals under the ground. Countries often select companies to help them extract their natural resources, so they can benefit from the capital, technical expertise and experience of private extractive companies. This also helps countries offset some of the financial risks associated with the exploration process. How governments decide which companies will have the right to extract, and on what terms, is referred to as licensing or allocating rights. There are important factors at stake when a government enters a licensing process, from picking the right company to limiting corruption and getting a good deal. The quality of the licensing process, and the mineral cadastre system by which the government keeps track of who has the rights to what, are essential to attract high-quality investors and ensure the country eventually collects taxes and royalties.

-

How the process works

Most governments use either open door or competitive bidding to select the company that will have the right to explore or extract natural resources in exchange for paying royalties, taxes or in-kind contributions.

Open door or competitive bidding?

In an open door process, sometimes called bilateral negotiations, companies are applying for resource rights on an ongoing basis. If the government decides that the company has the necessary experience, expertise and financing to carry out the project, it can enter into negotiations with the company. If not, the application is rejected. Many countries use a model contract as the basis of their negotiations, to minimize the number of terms up for negotiation, because it is easier for governments to make comparisons across bids when the bid rules limit the competition to a few variable terms. In an open door process, the company gets the mineral rights without an open competition.In Competitive tenders (including auctions), the government makes an open public announcement for companies to submit bids, and uses selected criteria to decide which company should have the rights. The steps in a typical competitive tender are shown in the graphic below:

- Planning: Government officials decide what blocks—segments of land or ocean floor—are going to be available and what terms are going to be open for bidding.

- Promotion: The government will then publicize the bid and ask parties to express interest.

- Pre-qualification: Governments will determine whether the interested parties meet minimum technical and financial criteria. Some countries choose to skip this stage, but it often takes place when the projects are more challenging.

- Call for bids: The government invites qualified parties to bid.

- Contract signature: After receiving the bids and determining the best bid by comparing the terms offered by each company, the government will issue a license or sign a contract with the winner. There are often some bilateral negotiations to fine-tune the agreement at this stage.

Steps in a typical competitive process. (Source: NRGI) There are arguments for either type of licensing, based on the circumstances. If there is good information about the geology of the block and investor interest is high, a competitive process is generally considered the best option. Companies compete against one another, strengthening the government’s negotiating position. However, companies are less likely to want to bid where there is limited or low-quality geological data, because there is greater risk of not making a discovery. In these cases, bilateral negotiations can be better at attracting initial companies to the country who can prove the viability of extraction projects.

Reputable companies also want to avoid being involved in corrupt deals and want assurance that they will be treated fairly in the licensing process, without political influence or favoritism shown to other companies. The integrity of the licensing process is therefore essential to attract high-quality companies. This will improve the chances of the discovery and extraction of resources, and the generation of revenues for the government in the shortest time possible.The terms of the agreement

“Licenses,” “permits” and “contracts” are legal documents that explain a company’s obligations in exchange for being granted the right to explore or extract the natural resource. What is covered in the agreement varies from project to project, but it often includes information about:- The geological area where companies have the right to explore or extract

- Timetables and processes for the project

- Financial and in-kind benefits shared between the company and the state

- Requirements for local economic development or infrastructure.

- Health and safety standards for labor

- Social and environmental responsibilities

- The process for oversight of obligations by the government.

These elements are discussed more in Chapter 4.

In competitive bidding processes and sometimes also in open door processes, some terms may be fixed, which means they are determined either by law or the rules of the bid. In some cases, all of the financial terms are fixed, requiring companies to bid simply on the amount of work and production they will undertake. Variable terms are the parts of the contract that are open for negotiation or for companies to outline in their bidding proposals. Governments often set the bid rules to limit the number of variable terms, to make comparisons across bids easier.

Keeping track of resource rights

A register or “cadastre” of natural resource rights is a database of those rights, which includes information such as who holds the rights, the coordinates of the license or contract area, when the rights were given and when they expire. In some cases, a cadastre may also refer to the public institution responsible for managing applications and granting resource rights. Registers or cadastres are important for keeping track of who has rights to what, and for creating a well-organized and stable environment for investment. How the information is organized and the extent to which it is publicly available varies from country to country.Some countries have invested in technology that links licensing information to geospatial data. This can result in helpful maps, often available online, that show what types of licenses are available where. This is the case in Uganda, which offers access to an online cadastre portal for its mining sector. Tanzania, Ghana and Sierra Leone have online mining cadastres that combine license information with payments. These can be accessed for free, but require registration. Some of the most sophisticated versions, like the one for Mozambique, have an interface that allows the user to click on a license to get more information about the contract terms and company ownership.

Consultation

Consultation is how and whether the community near the extraction site is involved in discussions about the extraction project. Industry experts often refer to a spectrum of consultation, from notifying a community, to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC). FPIC is a way of engaging a community before extraction takes place, in which its members are able to voice whether they believe the project should go forward. FPIC is required when companies work on land where there are indigenous people, but many companies have elected to use FPIC principles in all their projects. The image below summarizes some mining companies’ policies along the spectrum of consultation.

Overview of public commitments by mining companies to FPIC. (Source: Oxfam America, Community Consent Index, 2015) Some governments, like the Philippines, and international institutions, such as the World Bank and the International Finance Corporation, require companies working with them to engage in FPIC.

In practice, effective implementation remains an ongoing challenge. Consultations are often too late for communities to really say no to a project or shape its development. There is also a significant imbalance of power and information between local communities and large extractive companies. This allows companies to get away with tick-box approaches or controversial influencing tactics involving bribing, incentivizing or pressurizing of local leaders.

-

Government goals when entering a licensing process

Picking the right company

The government has an interest in selecting a company which will do the work efficiently and safely, while providing profit-based taxes and local content. There are different kinds of extractive companies and the requirements for the “right company” will depend on the type of license and the context of the extraction.In mining, for instance, some companies specialize in exploration (often termed “junior companies”). On making a discovery, the company must either secure further funding or be bought out by a larger company with the resources to conduct operations. New or less experienced companies can be successful in mining exploration, because, in contrast to oil extraction, it costs less to determine whether a mining project will be profitable. As a result, if a government grants an exploration license to a small company with little experience, it is not necessarily a sign the government picked the wrong company. However, some companies acquire licenses only to speculate on their value, holding the license without conducting work and later selling it at a profit, while the country is yet to see benefits.

Limiting corruption

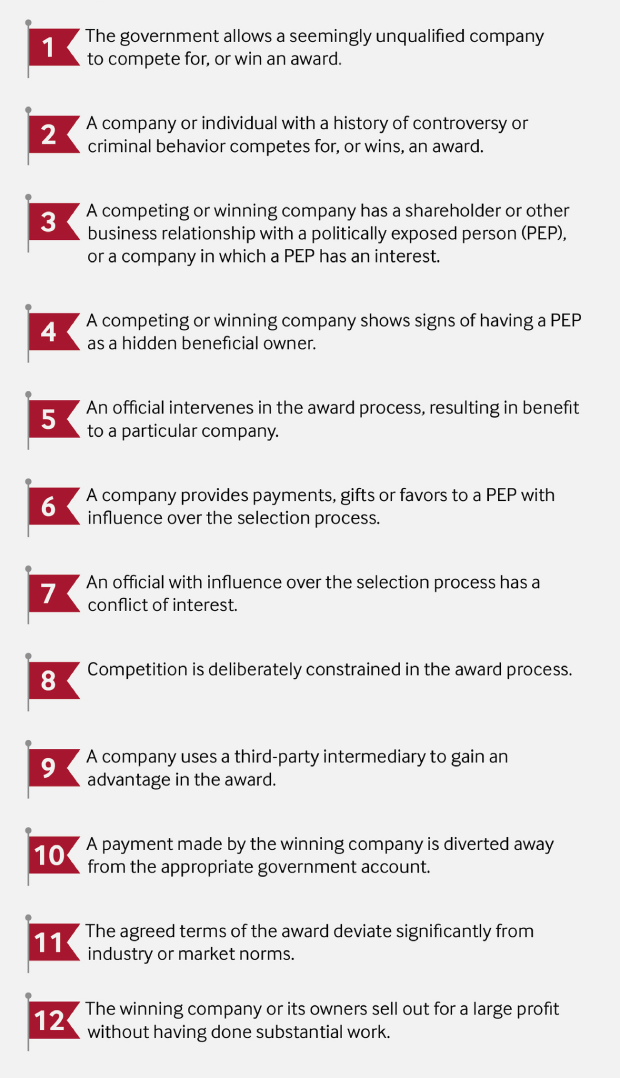

Corruption allows elites or connected people and dishonest companies to capture or take the benefit of the country’s resources, while the country as a whole loses out. Corruption disrupts the normal selection process, increasing the chances that an unqualified company is chosen, the terms of the deal are not as good for the country as they could be, or public money is stolen.Corruption can take many forms, from companies bribing public officials who have influence over the selection process, to using secret ownership structures that hide who really stands to benefit. In 2017, NRGI analyzed over 100 cases involving accusations of corruption during licensing in the oil, gas and mining sectors. The study found 12 red flags that showed patterns of potential corruption. When a deal has one of these flags, it does not mean corruption necessarily took place, but is a sign that more questions should be asked about the process.

12 red flags showing main corruption risks in the licensing process. (Source: NRGI) The full report is available here. See also the investigative tips in the Story Leads and Research Steps section below.

Knowing who stands to benefit from licensing: Beneficial ownership

Read more

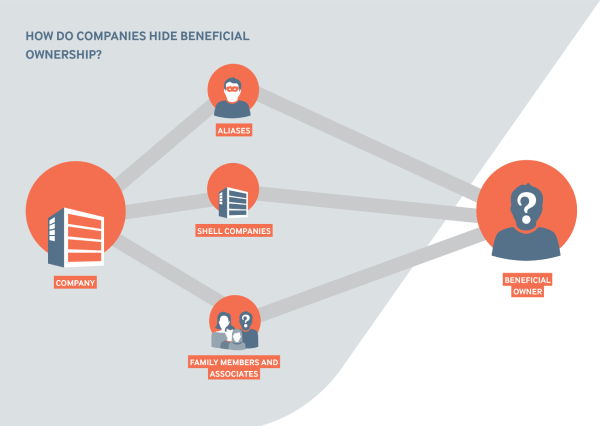

Hidden beneficial ownership of companies is a major way for corrupt people to benefit from licensing. Using anonymous shell companies allows companies to hide bribes, and politically exposed people (PEPs) to hide the benefits they receive. PEPs are people with a prominent public function, for example, as a politician, minister or general. They can use their position of power to influence the licensing process. This is why most countries make it illegal for government officials or their close associates and relatives to own companies applying for extractives licenses. However, regulators are rarely required to check whether such PEP interests exist when screening license applications. As a result, global campaigns for governments to disclose who effectively owns and controls a company that applies for or holds resource rights have grown significantly in recent years. The example of the Nigerian Premium Times in the reporting examples below shows how journalists can play a critical role in monitoring PEP involvement in the award of licenses, in particular by scrutinizing how PEP interests are being screened.

How companies hide beneficial owners. (Source: NRGI) → NRGI’s 2018 briefing on beneficial ownership screening provides practical details about reducing corruption risks relating to secret company ownership. This short guide includes infographics and simple explanations that may be helpful to communicate to a broad audience.

Story leads

Research questions and reporting angles

Below are story angles for reporting on licensing in a particular country, based on a sequence of research questions. See Chapter 1 for more general story planning guidelines.

Coronavirus disclaimer!

-

A. Does the government apply good practice in an ongoing licensing round?

1. Find out the rules. Research what the law says about the allocation of resource rights in a country and check whether the proposed rules for this award process are different from the law.

- Establish the general rules for licensing. Key places to look for rules on the bidding process, apart from national sources, include:

- The Resource Governance Index. The Resource Governance Index (RGI) country profiles may give an overview of the licensing process. Users can obtain more detail by downloading the data explorer and reviewing the research findings for individual RGI questions. Question 1.1c provides information on how the legal framework allows the government to allocate resource rights. By following the source documents for the questions related to a specific country, it is possible to see the laws or policies about the country’s licensing process.

- EITI reporting. EITI reporting must explain the rules that apply to the allocation of resource rights. These reports are usually published annually and can be found on national EITI websites or the international site.

- Investigate which rules apply for the ongoing licensing round. The rules may differ or be more specific for the current licensing round. Usually, the regulating agency for licensing (a state-owned enterprise (SOE) or ministry of petroleum or mining) will announce the rules for a specific licensing round, usually called “bid protocols”, on its website or through a press conference. The industry press is also a good source of information about ongoing bidding rounds (see “Sources” below).

2. Compare a country’s process with other countries.

- The Resource Governance Index assesses the transparency of resource-rich countries’ licensing in their legal frameworks and in practice. The “value realization” aspect of the index includes several questions on different aspects of licensing. The Compare Countries tab of the website can compare how up to three countries perform on different aspects of the index. By opening the licensing component (under “value realization”), users can compare country performance on the transparency or clarity of different aspects of licensing.

- The RGI Data Explorer. The RGI Data Explorer allows for more detailed investigation and comparison of each licensing question, with explanations of the results and links to underlying source documents. This can be used to compare countries or entire regions.

3. Compare a country’s current process to global standards. Transparency is at the core of licensing processes good practice. A reporter can look for previous assessments of the country’s transparency or compare the country’s transparency with standards of good practice.

- EITI Validation. The EITI checks or “validates” implementing countries periodically, to assess whether they are disclosing information in line with the EITI Standard. A detailed validation scorecard is available on national and international EITI websites. The scorecard shows whether a country made progress in disclosure for each of the aspects of licensing. There is a brief explanation for each score.

- Good practice. Open Contracting for Oil, Gas, and Mineral Rights is a guide published by NRGI and the Open Contracting Partnership in 2018, describing global norms and good practice for allocating resource rights. It outlines how good practice requires public disclosure of:

- How the licensing system is meant to work and the actors involved

- The planning process, including decisions about which areas should be subject to licensing

- The rules that will lead to the actual allocation and award of contracts and licenses

- The terms of the agreement struck with the winning company

- The implementation process, so citizens can check on whether the government and companies are meeting their obligations.

4. Follow up with human sources.

Public officials or relevant staff at the regulating agency can explain whether they have considered how other countries do in comparison and why a particular country falls short. Their explanation of differences can help bring updated considerations into the analysis.

Coronavirus disclaimer! - Establish the general rules for licensing. Key places to look for rules on the bidding process, apart from national sources, include:

-

B. Is the company the government picked qualified?

1. Find out the rules. Research what the law says about what company qualifications, if any, are required in your country.

- Establish the general rules for licensing. Key places to look for rules on the bidding process, aside from national sources, include:

- The Resource Governance Index. The Resource Governance Index (RGI) country profiles may give an overview of the licensing process. Users can obtain more detail by downloading the data explorer and reviewing the research findings for individual RGI questions. Question 1.1c provides information on how the legal framework allows the government to allocate resource rights. By following the source documents for the questions related to a specific country, it is possible to see the laws or policies about the country’s licensing process.

- EITI reporting. EITI reporting must explain the rules that apply to the allocation of resource rights. These reports are usually published annually and can be found on national EITI websites or the international site.

- Investigate which rules apply for the ongoing licensing round. The rules may differ or be more specific for the current licensing round. Usually, the regulating agency for licensing (an SOE or ministry of petroleum or mining) will announce the rules for a specific licensing round, often called “bid protocols”, on its website or through a press conference. The industry press is also a good source of information about ongoing bidding rounds (see “Sources” below).

2. Understand the context. The geology, timing and geography can influence what type of company skills are best suited for a particular extraction site. Industry press and experts can provide useful insight into the context:

- Geology. What type of mineral is being extracted and what is the grade? Are there other minerals in close proximity to the mineral that will make it easier or harder to extract? What type of extraction process is most common for this type of mineral?

- Timing. How does this extraction project fit into the country’s overall story of extraction? Is it the first project of its kind or does the country have a proven history of supporting extraction projects like this? What is the global demand for this product at this time? What is the country’s current global reputation for supporting business?

- Geography. How easy or hard is it to reach the extraction site and transport the mineral to the market? Are special skills needed to reach or transport the mineral?

3. Assess the qualifications of the winning company. Research into the company itself can provide insight into whether its skills fit the criteria required by the government (if these exist) and the needs of the context. Useful sources of information about the company include:

- Company website. A company’s website usually lists details of projects it has worked on, its clients, assets and financing, and whether it is publicly listed. This information can show whether the company has experience working on projects in similar contexts or with similar requirements. Reporters can also follow up with contacts or news outlets in countries where other projects took place, to find out about the company’s performance on those projects. Note that if a company does not have a website or does not list this information, it does not prove lack of qualification, just that reporters need to find the information elsewhere.

- Research industry sources. The industry press (see chapter 1) can offer useful insight into a company’s past experience. Reporters can also interview industry experts about a company’s reputation and experience. Again, a lack of information in this area does not necessarily show a company’s lack of qualification, but it does signal the need for reporters to ask more questions.

- Bid applications and government assessment. In some countries, the government publishes bids and gives an explanation about why a particular company was selected. In this case, reporters can assess whether the application fits with other information available about the company or criteria for the bid round. Follow-up questions can also be directed towards the government officials making these decisions. Did the winning bid receive the highest-ranking score from whoever evaluated bids? If not, why was it chosen?

- Check company registration. To bid, companies usually need to be formally registered somewhere. Check the national corporate registrar for the country where a company is registered, or online foreign registrar databases. Databases like Open Corporates can provide key information for some public companies. Several categories can offer useful insight on a company:

- Find the date when the company was set up. How long did it exist before it applied for or won the license?

- Assess personnel. Try to find names and identifying information (such as date of birth, addresses, pictures or work history) for the company’s principal officers and directors. Through interviews and online materials (CVs, biographies or social media profiles), assess whether they have relevant work experience. Industry sources can also reveal whether the company has the human resources needed to develop the license (such as engineers, project managers or geologists).

- Check the company’s official purpose. In many countries, when a company is formally registered, it has to specify its intended corporate purpose or scope of work. Do these relate to the kind of work needed to successfully develop the license?

- Visit the office. Obtain the company’s registered address or physical office address (from its website, a business card, a tender advert, its corporate registration file or its license application). Visit the address and see whether there appears to be a functioning office there—or whether the address even physically exists. If there is an office, how many people are working there? Is the company sharing the space with anyone else? The official office address is not proof of qualification, but its description can add color to a story, and seeing it can lead to additional questions. Journalists should follow adequate safety measures when reporting from the field.

4. Investigate the company’s progress in exploration and production. In some instances, companies who have become license holders will sit on deposits, without developing them, purely for speculation. This can result in significant revenue loss for the country.

- Check whether exploration is effectively underway.

- Some companies will report their exploration progress in their quarterly or annual reports to investors. If the project has potential to be very large, it is even possible that exploration progress is reported by the company in separate updates. However, the absence of the information does not mean that exploration is not underway. Companies are much more likely to report on exploration progress if it is going well, especially to impress current and potential investors.

- Another way to check whether exploration is underway, especially in the oil and gas sector, is to find out from industry contacts whether the license holder has hired a seismic exploration firm or other technical surveyors to explore the licensed block.

- Check whether production is taking place. Although gaining access to an extraction project is unlikely, reporters can take alternative approaches to assess whether extraction is taking place. Beyond on-the-ground observation (for example, are trucks leaving the site?) and interviewing locals, desk research can also be useful:

- Look up production figures. Reviewing production figures can indicate whether the company is extracting effectively. Sometimes the relevant ministry provides timely figures about production volumes, disaggregated at the project level—for instance, through the cadastre system. If a country implements the EITI, this information will be in EITI reporting. Some companies also publish monthly or quarterly production statistics on their websites.

- Find out whether taxes or royalties have been paid. Payments received by the government for a specific project can be an indication that extraction is underway. Several sources can be useful:

- EITI reporting. If a country implements the EITI, annual EITI reporting will show whether a company is making any payments. Find the relevant national website here.

- The NRGI database of company payments to government. NRGI’s resourceprojects.org website compiles payment data released by companies that are subject to mandatory disclosure laws in the EU, Norway and Canada. The data is searchable by country or by company to show whether there are any payments associated with particular licenses.

- Company websites and other national websites, such as Ghana’s Public Interest and Accountability Committee.

- Look at trade data. If a project is the only one for a particular mineral in a country and there is no production data from the above sources, UN COMTRADE will show whether the mineral is being exported from the country. If there are exports, there must be production.

- Establish the general rules for licensing. Key places to look for rules on the bidding process, aside from national sources, include:

-

C. Did someone have influence who should not have?

In its Twelve Red Flags report, NRGI looked at over 100 cases of potential corruption in licensing (see also Basics). In over half of those cases, there were signs that the winning company had ties to a politically exposed person (PEP). Instances in which an official/PEP is listed as a company’s legal shareholder are nevertheless rare. It is therefore important to note that hidden ownership can almost never be conclusively proven and is not easy to investigate. Usually, the best a journalist can do is amass different pieces of circumstantial evidence and present them carefully. Journalists may not be able to publish everything they uncover—for example, if it is too speculative, potentially defamatory or would risk exposing the source of the information (see also safety tips in chapter 1).

1. Find out the rules. Check whether there are rules about excluding PEPs in the application process:

- Resource Governance Index. The Data Explorer RGI question 1.1.7b assesses whether there are rules requiring disclosure of beneficial owners of extractive companies. Question 1.1.8b shows whether those have been followed in the period covered by the 2017 RGI, covering 2015-2016. Questions 1.1.7a and 1.1.8a can also help show whether there are asset disclosure requirements for public officials and whether these requirements have been followed in 2015-2016.

- EITI. Since 2020, EITI reporting must include information about the identity of beneficial owners of extractive companies, the level of ownership and details about how ownership or control is exerted.

2. Look into the people involved. Understanding who is involved in the company on paper can help indicate connections of people who should not be involved:

- Shareholders, directors, officers. Lists of the company’s legal shareholders, directors and officers are usually available as part of the registration or tax payment process. This information may also be found on the company’s website or in its annual report, stock exchange filings, a corporate register or various online databases. Review the list for:

- The names of any known government officials or PEPs.

- Business, family or social associates of an official or PEP.

- Any potentially fake or suspect names. These could include the name of a person or company for which no public records exist, a name that appears to have been deliberately misspelled, one that no one with relevant knowledge recognizes, a name that otherwise closely resembles some other, identifiable name, the name of a deceased person, or a known or suspected alias, particularly of a PEP.

- If the company’s legal shareholders include other companies, be sure to check who owns those as well.

If possible, show the list to knowledgeable industry sources and ask them:

- Do the names on the list match their understanding of who owns or controls the company? Is anyone missing?

- Do they know any of the people on the list? How did those people come to have a place in the company? Do they have any close political relationships?

- The name of the company.

- If the company has an unusual enough trade name (such as “Dragon Wing Petroleum,” rather than “Oil Services Co. Ltd.”), run variations of that name through the local registrar, Open Corporates or other open-source corporate databases and see who owns the companies that come up.

- Does the company have initials in its name (e.g., “DEM Corp.”)? Could its name be a combination of different initials or names, or an anagram of a person’s name? These can sometimes be unscrambled or matched to the name of an official who owns the company, or to their associates or family members. This is not uncommon practice among corrupt officials. You can also try this with named assets of the company (e.g., if it has a drilling rig called the “Maria Christina” and a suspected official has a wife named Maria and a daughter called Christina).

- Explore further potential connections.

- Check land, tax, operational safety and other regulatory records (if available) to see who owns, leases or pays dues on the company’s office building and other real or personal property, such as cars, planes or field equipment.

- Check the company’s registered or physical address by searching online or at the corporate registry, to see which other companies or individuals are linked to the address. Then ascertain who owns or controls those.

- Carry out social network analysis. See which officials the company’s legal shareholders, officers, directors or lower-level employees are connected to on social media or through other social ties. They may have attended the same schools or places of worship, sat together at weddings, funerals or other social events, or have family members, business associates or close friends in common. Or they may be from the same region, village, ethnic group or political party or block. Online research, interviews and paper sources such as school yearbooks, gossip magazines and event programs can all be helpful. Pay special attention to the connections of nominee shareholders.

- Is the winning company “close” to any official with decision-making authority over the license? In what way? What is the basis for their relationship (for example, employment or consultancy, shareholding, or social or family ties)? Is there any chance the official gave the company special treatment because of such links?

3. Investigate inappropriate relationships and anti-competitive behavior. Below are some broad questions covering common types of situations and behaviors that could suggest a company received undue advantage in a license award process. The right sources of information will vary by the question: Some will be documentary (e.g., records from the bid evaluation process), while others are things to ask human sources. Note that some of this information is not likely to be readily available in many countries.

- Did the winning bid receive the highest ranking/score from whichever actors evaluated bids? If not, why was it chosen as the winner?

- Did any official with high decision-making authority set aside or ignore the recommendation of whoever evaluated bids and choose another company instead? If so, what was the reason?

- Did an official with decision-making authority tell a company that it had to partner with another firm if it wanted to win, effectively “forcing a marriage” between the two? What was the reason for this? Who owns or controls the other firm?

- Did the winning company actually place a bid for the license it won or was it just declared the winner?

- Is the winning company “close to” any official with decision-making authority over the license? In what way? What’s the basis for their relationship (e.g., employment/consultancy, shareholding, social or family ties)? Is there any chance the official gave the company special treatment because of that?

- Did the winning company receive a right of first refusal or other preferential bidding rights over the license? Why? How was that good for the country?

- Did the government exempt the license from competitive bidding and allow the company to bid for it alone? Would a competitive bid have served the country’s interests better?

- Are there other companies complaining that they were not allowed to bid for the license? What happened? Why do they claim they were excluded?

- Was the time window the government set for bidding reasonable or was it too short for some companies to put their bids together in time?

- Are the companies that submitted bids for the license you’re interested in truly separate companies, or are they secretly working together to create the appearance of competition? Evidence could be common shareholders, officers or directors, shared offices or other corporate assets; one or more of the companies submitting a bid that looks unreasonable or defective.

- Did the winning company renegotiate the terms that it bid after it won? In particular, did the government allow it to renegotiate terms that were more favorable to it after it won the bid?

- Why do the losing companies think they lost?

-

D. Was everyone involved who should have been?

1. Check for a broad plan. Best practice is that before licensing begins for a specific project, the government creates a Strategic Impact Assessment and policies that show the big picture of how it plans to balance issues of land use, social and environmental impacts, and potential revenues.

- Investigate documents. Reviewing national extractive policy documents can lend insight into these broad tradeoffs. Resourcedata.org is a large database of country laws and policies on extractives that can be searched by country or content area.

- Ask key players. Ask government sources and oversight actors whether there is a concerted plan for how the government intends to involve various actors in weighing the positive and negative implications of extraction.

2. Find out the rules. Research what the law says about the consultation process and what might be applicable for this extraction project.

- National consultation rules. To understanding what, if any, requirements the country has for consultation, see national policies or laws on resourcedata.org, or in the description of the legal framework that is part of EITI reporting.

- International obligations. Some special cases mean that certain types of consultation are required by law:

- Indigenous people. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People requires that indigenous people give Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) for any project on their land. Reporters need to understand whether indigenous people are likely to be impacted to know whether FPIC applies.

- World Bank Projects. Projects funded by the International Finance Corporation or another branch of the World Bank must meet specific requirements for consultation throughout. If a project has funding from an international financial institution, even if not the World Bank specifically, reporters should ask whether these standards are being met.

- Good practice standards.

- Industry standards. The International Council on Mining and Minerals has created resources for its members to support stakeholder engagement. These include how companies approach communities and understand their perspective. Larger companies often have their own internal standards for how consultation should take place for their projects.

- Civil society perspectives. Oxfam has created a guide to FPIC in multiple languages. This gives perspective on the standards civil society expects when companies seek consent.

3. Check on what type of consultation took place, with what information, when. Consultation ideally takes place with multiple actors across different phases of the project. Interviewing different actors about their experience of consultation, when it took place and the information they were given is necessary to verify whether obligations were met. This includes interviewing:

- Local community. People who live in the community may not all have the same opinion or experience. To get a “community” perspective, reporters should talk to different types of people, including men, women, the young, the elderly and those from minority groups. These different perspectives can reveal whether a company’s rules and intentions were followed.

- Local government. Local government officials are often seen by the company as community representatives. It can be useful to ask local government officials how they were consulted, and what information they shared with the community, when.

- National government. National government officials can provide insight into what information they required or heard related to consultation. They can also give perspective on how the consultation results affected the government’s decision making.

4. Get perspective. Understanding how consultation takes place at other extraction sites can give reporting perspective and context:

- Within the country. Reporters can compare the consultation experiences of one community with those at other extraction projects within the country. This can show whether the government is consistently applying standards across different companies or types of mineral extraction.

- From other sites with the same company. Using contacts in other countries, reporters can research how a company conducted consultation processes in other countries. This can lead to an article that shows company trends or shortfalls in particular locations. International civil society groups can often be helpful connecting reporters to contacts in different countries.

Examples of good reporting practice

The examples given below can provide inspiration while preparing stories on licensing. Some highlight day-to-day reporting, while others are in-depth investigative reports.

-

Alleged bribery in license award (investigative)

BP to pay billions for suspicious Senegal gas deal

This 10-minute documentary by BBC Africa Eye and Panorama describes alleged corruption in a lucrative gas deal off Senegal’s coast. A gripping investigation traces steps supposedly taken by the president’s brother to influence a licensing round and receive beneficial royalty rates. The report includes interviews with a range of actors and mixes documentary with human sources. It also provides comment from those accused of wrongdoing and gives their responses. The filmmakers take care to use easily understood language and to break down complex steps into digestible information. They also provide context to their audience, who might not be familiar with Senegal or the gas sector. The report could be improved by clarifying what payments the people of Senegal are getting, and comparing the current deal to industry standards. -

President’s daughters own gold mine in Azerbaijan (investigative)

Aliyev’s secret mining empire

This article by the international investigative outlet Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project shows how the daughters of the President of Azerbaijan were the secret owners of the country’s most lucrative gold mines. Using a combination of interviews, leaked documents and visual graphics, this investigation offers both narrative storytelling and an explanation of how hidden ownership of mines can work in practice. The story has an impact on readers because it offers character details that contrast the Azerbaijani President’s glamorous daughters with a geologist who works at the mine. By giving this attention to everyday people as well as more famous politicians and elites, the report connects with readers and shows how these issues relate to them. This story could be improved by explaining how the mine’s suspicious deal has lost the government money and impacted citizens beyond those who work directly at the mine. -

Identifying suspicious trends in mining ownership in Uganda (day-to-day)

Who owns the rights to Uganda’s minerals?

This brief investigation published in the Ugandan national paper, the Daily Monitor found that a prominent pastor and the former energy minister owned most of the rights to the minerals in Uganda. This story does an excellent job explaining data from the Ugandan Directorate of Geological Surveys, while creating a narrative about the beneficial owners of these mining rights. The author also uses humor and characters to tell the story. While the story highlights gaps in Uganda’s mining license allocation process, it could have gone further in explaining why having so few owners could be a problem for the citizens of Uganda. It could also be the beginning of a deeper investigation into the dangers of politically exposed people being involved in licensing. -

Covering licensing delays in Tanzania (day-to-day)

Minister clears air on LNG project delays

After months of delays on a liquid natural gas (LNG) project, this article, published in the Tanzanian national paper, the Daily News, explores why the project was late. In addition to providing perspectives from different branches of government and industry, the article explains the complexities associated with negotiating the terms of a large gas deal. As a result, it helps manage readers’ expectations about how long negotiations should take and what risks can be involved. The author does not seek blame with either government or companies, as can often happen in reporting with multiple sides, and instead explores the reasoning provided by different actors. This type of reporting could be deepened by adding perspectives from neighboring countries on how quickly or slowly gas deals were negotiated and with what rates of success. -

Money changing hands during licensing in Nigeria (investigative)

Investigation: The fraud called Malabu Oil and Gas (Part 1)

This article was published in the Nigerian daily newspaper, the Premium Times, several months into the paper’s investigation of licensing of an oil block. It summarizes what is known about the involvement of the president and other high-ranking officials in creating a shell company that was awarded an oil block and paid billions of dollars by major oil companies Shell and Eni. The paper’s investigation was aided by the release of the Panama Papers, although it had already been working on uncovering corruption at the time. The article is complex, but allows readers who had been exposed to pieces of the puzzle for months to process all the information in a clear narrative. -

Behind the scenes of the Malabu case: Testimony by Nigerian Premium Times Reporter Idris Akinbajo

Idris Akinbajo is an investigative journalist whose interest is in reporting cases of corruption, failure of regulatory agencies, and human rights abuses. He is known for leading the groundbreaking investigation into the grand corruption scandal in the Nigerian oil sector, popularly called the “Malabu scandal,” while working at the daily newspaper, the Premium Times. An early article in the investigation can be read here.

Idris also followed the story across the globe through the courts and political consequences. Since then, he has continued to follow extractive sector corruption cases. He is the former head of the Premium Times investigative desk and is now its managing editor.Below is the transcript of an interview with Idris, Listen to the full podcast here:

Transcript

Full transcript

1. The Malabu Oil deal is a good example of corruption in the oil and gas sector in Nigeria—and, of course, what’s possible in other resource-rich countries. What lessons on the governance of licensing processes can one learn from the Malabu case?

Although the Malabu/OPL 245 contract was awarded during the military era [in Nigeria], I would say two major lessons are to be learnt from the process. One is for relevant government agencies to do their due diligence and ensure that only qualified oil firms are awarded oil licenses. In the case of Malabu, what happened was the creation of a briefcase company that had a non-existent character as a shareholder—which is against Nigerian laws and ordinarily should be a crime that one should be prosecuted and jailed for. So the first lesson is that relevant agencies should do their due diligence. If CAC [Nigeria’s Corporate Affairs Commission] had done its due diligence then, if DPR [the Department of Petroleum Resources] had done its due diligence, then Malabu would never have been awarded OPL 245. That, for me, is a major lesson to learn. The other lesson is to ensure that politically exposed persons are totally removed from having interests directly or indirectly in companies that are bidding for government contracts. Public officials should not in any way, either directly or through relatives or friends, be involved in owning or managing companies that are bidding for government contracts. What we saw with Malabu is that we had a sitting head of state whose son owned 50 percent shares in the company, a serving ambassador of Nigeria whose wife had about 20 percent shares in the company. Though we could say this happened in the military era, it’s still happening now, so these are two key lessons that Nigeria must ensure do not occur again.2. Why should the media care? Why did you and Premium Times care?

The first reason why we [Premium Times] cared when we first got alerted of the Malabu scandal was the volume of money involved when the 2010–11 agreement was signed. About 1.1 billion [U.S.] dollars, a large chunk going to an individual, and for a country that then was facing several crises—inadequate schools, uni lecturers and doctors on strike—so we were concerned that how can this large chunk of money that should ordinarily go into government coffers go into private hands? Secondly is the value of the oil block—this was an oil block that by industry estimates could have provided enough oil and gas that could power the whole of Africa for a good period. So the value of the block, the amount of money involved, but also the level of impunity of the whole process made us worry that something like this should not be let go without adequate investigation.3. What challenges did you face in covering this important story?

The first challenge we faced was access to documents…. When we first got notified about the dealings, about the award, the signing of the contracts, we first tried to get copies of the three contracts because the 2010–2011 contract was signed between three parties, but in different forms… so there was one between Shell and the Nigerian government, there was one between the Nigerian government, Shell and Eni, and there was Malabu and Shell… so getting access to all these documents. We were also trying to get access to various older CAC records. We were not only interested in the current CAC records of Malabu, but also all the alterations that had happened since when Malabu was formed in 1998. The third was getting relevant parties to talk, parties who were directly involved in direct negotiations… Getting them to talk even off the record was a challenge. Of course, that’s one of the challenges that investigative journalists face, but we were able to surmount the challenges. We got the info we needed.4. What lessons can other journalists learn from your coverage of this story—e.g. tools, skills that are necessary to develop, and general tips?

The first [skill] is patience: never give up when you’re pursuing a story of this nature, even if it seems you’re facing barriers in accessing these documents or accessing sources. Keep pushing. Some of these investigations take months, years to get done, so never give up. The second thing is to be able to interpret data and relevant documents. It’s very key. You’d see some court judgments, like the U.S. court judgments, related to the matter…very bulky documents and you wonder, why do I have to read this 200-page document? Why do I have to interpret these legal terminologies as a journalist? But you really have to do these things to fully understand the matter. So I’d recommend to journalists that they should be willing and patient enough to read tons of documents that are relevant to the investigations that they’re pursuing. The third is to be principled and upright. Someone once asked me why I was not scared for my life in pursuing this story, and even going as far as serving as a witness on the trial in Italy, and I told the person that all the players involved in the Malabu scandal know I’ve never collected a dime from any of them, despite knowing all of them. So they know I’m not doing it for the money. So for that reason I know there’s nothing for me to be scared of. If they had heard that I ever collected money from any of them, then the other party would have been able to say: he’s doing it for money, let’s go after him. So my advice to journalists, particularly to [my] Nigerian journalists, when you’re doing investigations, no matter what you’re offered, please be upright. It’s very key.

Cultivating sources is very key to investigative journalism. Some of the documents we sourced for this story would not have been got or possible if we had not cultivated [the] sources that we did. Sources both here and in the U.K., sources involved in the negotiations, top government officials, serving ambassadors. Journalists must ensure, first, for a story like this, that enough story mapping is done. Adequate story mapping is important. If you do your story mapping very well, you’d find that it’s not all sources that are difficult to find. You just need to identify the different types of sources that you need. There are some low-level sources that have access to big documents, so, where can I get this document, where can I get this source? Is there a person who served in a certain office that would be willing to talk now that they’re no longer in the office? So source cultivation is very key to ensuring success on a story like this, and also working with various relevant groups locally and internationally.

Sources

Below are sources that can contribute to different angles on stories about licensing. Some will be similar across different aspects of mining, oil and gas reporting and are repeated across chapters, while others apply specifically to licensing. When possible, there are direct links to institutions in the main target countries of “Covering Extractives”: Ghana, Myanmar, Tanzania and Uganda.

Coronavirus disclaimer!

-

Public institutions

Government bodies

In some instances, a state-owned enterprise (SOE) will be responsible for issuing licenses. This is mostly the case in Myanmar, where the Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise grants oil and gas exploration and production rights to companies, and the Myanmar Gems Enterprise manages the mining licensing process. Journalists interested in covering licensing processes in Myanmar should also keep an eye out for tender advertisements published on the Facebook page of the Oil and Gas Planning Department at the Ministry of Electricity and Energy.

In many countries, the relevant ministry or sector regulator is in charge of allocating rights, such as in Tanzania, where the Ministry of Minerals is the government entity responsible for awarding mineral rights. Similarly, in Uganda, the Ministry for Energy and Mineral Development has the authority to issue mineral licenses. The Petroleum Directorate will hold further information about oil and gas licensing, while the Directorate for Geological Survey and Mines is responsible for managing information about mining licenses. In Ghana, the Ministry of Energy and Petroleum is the licensing authority, though it consults with the Petroleum Commission and the Minerals Commission on some aspects of the licensing decision.Oversight institutions

In some countries, parliament is involved in approving the contract after a licensing or negotiation process is completed. In others, parliament can have input into the licensing process or the resulting outcomes through legislating clear rules for the licensing process and holding hearings on its implementation. Reporters can ask members of parliament about what checks they make on the licensing process and how they are monitoring its success.Staff at other agencies, such as supreme audit institutions, can also provide useful information about their review of the licensing process generally or the result of specific deals. For example, the National Audit Office of Tanzania conducted a performance audit of the licensing process for natural gas. Similarly, anti-corruption agencies such as the Nigerian Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offenses Commission can be involved in investigating potential corruption in licensing. These agencies often compile documents relevant to in-depth reporting, although these may not always be publicly available.

-

Experts, civil society and watchdogs

National groups

Experts from civil society and academia can be helpful commentators on licensing and allocating rights. They can distance themselves from government or company interests and offer a different view of what is in the people’s interest. However, they too can have biases, so seeking a second or opposing opinion is warranted for balanced reporting.Where relevant, journalists are welcome to contact NRGI country offices, where staff can provide connections with the right expert internally.

Other options for connecting with competent civil society or academic figures include:

- Publish What You Pay (PWYP), the global coalition of civil society organizations campaigning for a fair use of natural resources. PWYP has over 700 member organizations in 50 countries, working on numerous issues, including licensing. Its national coordinators are able to direct journalists to a range of expert contacts.

- In EITI member countries, there will be civil society representatives on the national multi-stakeholder group. The national secretariat could also offer recommendations for civil society groups that specialize in extractive sector management.

International civil society

Licensing and beneficial ownership have become an area of interest to many international civil society and academic groups. The Open Contracting Partnership is an international effort to add transparency to government contracts and the processes that award them. Global Witness is respected for investigating corruption in particular cases of licensing that have not benefited citizens. -

International organizations

International organizations

The International Monetary Fund’s fiscal transparency guide sets some basic standards on licensing disclosures, and the World Bank has produced publications and guides exploring the subject in more detail. It can be relevant to contact their country staff to obtain further insight into the allocation of mineral rights.Multi-stakeholder initiatives

The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) is a multi-stakeholder initiative that supports transparency in resource-rich countries through an international standard implemented by member countries. EITI implementing countries are required to annually disclose the process by which licenses were transferred, the criteria used in decision making, the title owner and any deviations from the usual legal framework. Member countries are also required to publish the beneficial ownership of all licenses as well as all contracts entered into or amended after 1 January 2021. Although EITI data is often published slowly, the descriptive reports and the types of information available can be used to ask questions of ministries for more current stories. The national multi-stakeholder group that oversees a country’s EITI process can also be a source for discussions on what information about licensing should be publicly available.The Open Government Partnership (OGP) is an international multi-stakeholder initiative that supports countries in processes of transparency and accountability. Multi-stakeholder groups within countries that have signed up to the initiative set country goals for openness in sectors they prioritize. Beneficial ownership has been a major initiative of the OGP globally and in many implementing countries. Reporters can follow up with national OGP committees.

-

Private-sector sources

The industry press can help reporters keep track of upcoming and ongoing licensing rounds, but many outlets require payment. In the oil sector, rigzone.com is useful for following news about exploration activities and has the advantage of being free. The Oil & Gas Journal is very useful for background knowledge.

It can be important to contact companies involved in the licensing round to understand a different perspective and hear how this investment fits into their overall portfolio. Reporters can contact the national office, which may give information about a specific project, or the international headquarters, which can provide context about a company’s good practice when participating in licensing and negotiations. In addition, companies often release information about a prospective oilfield or mine site on their website, to attract or reassure investors.

-

Data sources

Beneficial ownership

To help investigate who owns a company, the Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN) has a useful tip sheet on how to research corporations and their owners. A growing source of information about beneficial ownership is the Open Ownership register, which is global and links across jurisdictions and industries to publish data about beneficial owners. The data comes from regulatory sources such as the U.K.’s Persons of Significant Control Register, from EITI reporting and in some cases from companies themselves which have voluntarily submitted the information. In addition, crosschecking a corporate name on OpenCorporates can provide insights into the links between companies. With information about more than 100 million companies, OpenCorporates is the largest open company database in the world and can be a helpful tool to make connections between different companies or jurisdictions.GIJN also provides more specific advice on how to approach asset disclosure by public officials. This can be practical if you suspect that a PEP is involved in the company you are looking at.

Cadastre and license registries

Most countries have a database where they keep track of the geospacial information about where licenses are allocated. This usually includes helpful maps, often available online, that show what types of licenses are available—as in Uganda, which offers access to an online cadastre portal for its mining sector. This type of information was used in the reporting example above by the Daily Monitor. Tanzania, Ghana, and Sierra Leone have online mining cadastres that combine license information with payments. These can be accessed for free, but require registration.

Voices

In the short videos below, a South African civil society representative and two Argentinian stakeholders, one from the Ministry of Production and Labor and the other from the Chamber of mines, share their views about the allocation of licenses.

Learning resources

-

Video overviews

In this 15 minute video, Mark Moody Stuart, Chairman of Hermes Equity Ownership, provides an overview of where and when companies decide to invest in an extraction process.

In a 19-minute presentation, Paulo de Sa from the World Bank gives an overview of how rights are allocated in the extractive industries. He shows the World Bank’s perspective on good practice with six different principles: a focus on predictability, security, transparency, disclosure, and a lack of discretion and discrimination.

-

Key reports

NRGI has a five-page plain-language primer on licensing that gives an overview of the process of allocating resource rights.

Two leading reports provide background about when and where to spot corruption in extractive licensing process:

- NRGI’s “Twelve Red Flags: Corruption Risks in the Award of Extractive Sector Licenses and Contracts” identifies trends based on analyzing hundreds of cases of corruption in licensing. It provides 12 situations when oversight actors such as reporters should begin asking more questions because of corruption risks.

- Following extensive research in 18 resource-rich countries, the non-profit organization Transparency International published a comprehensive report looking at what can go wrong in the approval process for mining licenses. The report focuses on key corruption risks in the different licensing phases, offering case studies and key recommendations on how the process can be improved to limit corruption. Its risk assessment tool can also be useful to journalists.