Money flows

Managing extractive revenues

Download the full chapter in PDF

Why it matters

Why does this matter to your audience?

- Over the last decade, governments around the world have collected approximately USD 3.8 trillion per year in oil, gas and mining rents.

- Good management of these revenues can help a country to build valuable infrastructure—such as schools, hospitals and renewable energy—create jobs, ignite an economic boom and attract further investment. But if managed poorly, these resources can contribute to economic stagnation or, in the most extreme cases, finance authoritarian regimes or wars. How resource revenues are managed makes a big difference to whether a country prospers or suffers from natural resource exploitation.

- Revenues from extractive projects come with particular risks. Because they are volatile, finite, big and location-specific, they can be harder for countries to transform into long-term development. This makes it particularly important for people in the country to keep a close watch over how these revenues are used.

- Other parts of the economy can suffer as a result of the quick, large flow of extractive revenues. These can cause inflation, which can hurt local companies. Harmful effects can last decades, as in Russia and Iran, where manufacturing industries have never recovered from their sudden decline.

- The management of money from extractives has often been clouded in secrecy or has taken place through a variety of processes. This means citizens cannot ask questions about important government spending. New campaigns from civil society have made more of this information available.

The basics

Oil, gas and mineral revenues come with different risks and opportunities from other revenues, because they are particularly volatile, finite, large and produced in a specific location. This means that they often need to be managed with extra care.

-

Managing money from extractives

If the revenue from extractives is large in relation to the economy or national budget, governments often consider how to treat extractive revenues differently, for reasons including:

Planning for volatile revenues

Revenues from natural resources tend to be volatile, going up and down with prices and supply. If a government puts all its revenue into the budget, the country’s spending would also go up and down, and be unpredictable, sometimes harming the economy. To prevent this, a government can create rules about how much of the revenue to spend or save each year. Often this includes saving in good times and using savings in bad times. In recent years, Argentina, Ghana, Mongolia and Venezuela have taken on large debts with each downturn in revenues. In contrast, Peru passed a Law on Fiscal Responsibility and Transparency in 1999 that limits public debt. Such laws are called fiscal rules—rules that permanently constrain public finances. Fiscal rules can be a useful tool to help manage boom-bust cycles and keep resource-rich countries from overspending and going bankrupt.Mitigating “Dutch Disease”

Some countries’ natural resource revenues are so large that they overwhelm the economy, causing local prices to rise and expertise to shift from local industries into the oil or mineral sector. As a result, countries experience the “Dutch disease”, where the discovery and production of natural resources harms other exporting industries and workers. One way to mitigate the Dutch disease is by putting some of the extractive revenues into foreign investments.Growing the country’s economy using a finite resource

Because natural resources are exhaustible (once taken, there is nothing left underground for future generations to use), countries can consider how much the current generation should benefit versus how much should be invested for future generations. Investing for the future can take many forms, including saving money in a fund, investing it in financial assets, paying off public debt, or spending money on citizen education, healthcare, and infrastructure that will benefit the whole country. In general, poorer countries can achieve the biggest value by investing more domestically, while richer countries may want to invest more in foreign assets. Governments investing resource revenues domestically must decide whether to invest the money through the normal budget process or through a special institution like a development bank. They must also choose where to invest it, for example, in specific projects such as ports, in specific sectors such as agriculture or tourism, or building a better business environment through initiatives such as better education.Sharing the money across the country

The government must decide how to share the revenues from natural resources across the country. Should the benefits be distributed equally across the states or regions, should poorer states or regions get more or should producing regions benefit to a greater degree than non-producing regions? For example, in Nigeria, the national government gives 13 percent of the total revenues from oil sales to the states where oil is produced.Managing expectations

Natural resource wealth, or even news of possible discoveries, brings big expectations of quick benefits. Many governments respond to these expectations by increasing public spending before any oil or mining money has started to flow, particularly on large, visible projects like highways and airports. Such spending can be the result of resource-for-infrastructure deals or heavy borrowing against future revenues. However, it is often based on overly optimistic projections of future revenue, putting countries at risk of debt. Policies that can prevent a country from such heavy future debt include honest forecasts of revenues and the risks of extraction, and lowering public expectations through better communications.→ The NRGI primer about revenue management provides further details about the special challenges that come with managing public income generated by extraction.

-

Where does the money go?

Every resource-rich government makes decisions about how to allocate money from the extractive sector to different levels of government, various institutions or directly to citizens. Below we discuss five of the most important tools used to manage resource revenues:

- the national budget

- Sovereign wealth funds

- Development banks or strategic investment funds

- State-owned enterprises

- Resource revenue-sharing systems.

The national budget

Money from oil, gas and mining is most often spent through the national budget process on government goods and services. However, governments have chosen to spend this money in many different ways.Choices of which institutions to build and which not to, and how to spend the money, are key to transforming wealth into well-being. Many successful countries have implemented 5– or 10–year development plans that coordinate the spending across the yearly budgets. For example, Malaysia has had success transforming its oil wealth into strong development through 11 medium-term five-year plans since 1971. These plans can encourage governments to focus on spending priorities that trigger sustainable growth, rather than on showy infrastructure projects or increasing government salaries unsustainably.

Another key to successful spending through the national budget can be spending that will help the country diversify the economy and create economic stability. This can include open trade and investment policies, investments in education and macroeconomic stability, and interventions in private markets to encourage certain sectors of the economy.

Sovereign wealth funds

Governments can establish special accounts of money outside the regular budget process, to manage their revenue. When these funds have bigger economic objectives and invest at least partly outside the country, they are referred to as sovereign wealth funds (SWFs). As of 2019, there were approximately 60 SWFs financed by mineral or hydrocarbon revenues or by fiscal surpluses in countries dependent on natural resources.

These funds are generally established to save money for future generations, stabilize government spending, or create resources to finance a specific government program, such as pensions, environmental protection, or education. In some places, like Botswana and Chile, funds were key to the country’s success in transforming resource wealth into development. Unfortunately, funds in other countries are riddled with stories of mismanagement and corruption. One of the most extreme examples is the Libyan Investment Authority, which lost over USD 1 billion through mismanagement.

SWFs can also harm a country when they save money and earn a low-interest rate, while the government borrows at a high-interest rate. In this case, each dollar saved rather than used to pay off debt costs the government money. For example, Ghana quickly increased its national debt after finding oil and establishing a fund with a lower return rate than the interest on the debt.

Countries have found the most success when they have passed well-designed revenue management legislation and instilled a culture of transparency and accountability. Often this includes creating fiscal rules that are clear about how much money the government must save or spend each year. It also requires very close oversight, internally and externally, to make sure everyone with access to the money is using it in the country’s best interest. NRGI research has found that half of all resource-financed SWFs do not publish quarterly financial statements and are therefore hard to assess.→ Read more about adequate investment rules, fund structures, and oversight rules in the NRGI primer on natural resource funds and a guide on establishing a SWF, or watch this introductory 11-min video on sovereign wealth funds.

Development banks and strategic investment funds

Another way to spend resource revenues outside the national budget is a so-called “strategic investment fund.” In practice, these funds act as public-private partnership (PPP) funds, national development banks or other types of state-owned companies. These funds or banks are used to provide loans to projects in the country, which will ideally spur development. Sometimes development banks invest in projects without a private-sector partner, but on commercial terms. The lack of partners increases the risk associated with a given investment.The global experience with strategic investment funds, PPP funds, and national development banks is mixed. Brazil’s Banco Nacional de Desenvolvimento Economico e Social is widely cited as an example of an effective domestic investment institution. However, as with SWFs, some strategic development funds and development banks have been sources of patronage, corruption and mismanagement. The Development Bank of Mongolia, for example, has made many bad loans and is a major source of Mongolia’s state debt, which led to an IMF-led bailout. The $10-billion Russian Direct Investment Fund invests in domestic companies almost without independent oversight, creating a source of financing for supporters of the ruling regime, without the need for accountability. Many of the lessons learned from SWF and state-owned company governance can be applied to strategic investment funds and national development banks. These funds should have clear objectives, specific professional roles, and regular, accurate reporting mechanisms.

State-owned enterprises

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) often collect and manage extractive revenues on behalf of the state. Revenues that are kept or allocated to the SOE can be spent on running the company or other projects. As discussed in Chapter 3, large amounts of money can be spent through these companies, on projects ranging from oil rigs to schools and football teams.Fuel subsidies are one major item commonly covered by SOEs whose cost to society can be enormous. According to the OECD and the International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook, oil subsidies alone cost the Iranian state $40.2 billion in 2014, while gas subsidies cost another $22.3 billion. These energy subsidies are generally regressive, meaning that the marginal benefit to rich people is greater than to poor people.

Chapter 3 includes more information about the risks and opportunities related to revenue management in SOEs. As with other spending options, the risks are reduced when there are clear objectives for companies and meaningful accountability.

→ Read more about revenue management risks and policy responses in this EITI publication and NRGI’s report on national oil companies.

Resource revenue sharing

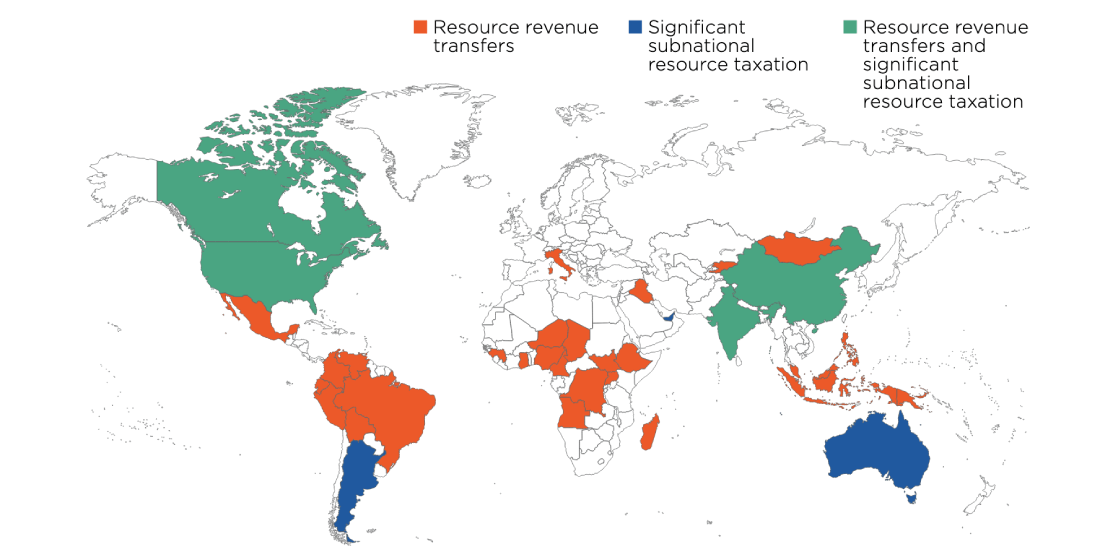

At least 30 countries have systems to share resource revenues with municipal, district, state or provincial governments. These funds mostly come through direct payments from companies to subnational governments, or transfers from national to subnational governments.

Map showing countries with natural resource revenue sharing (Source: NRGI, 2016) Direct payments: A company may directly pay a subnational government because of contractual obligations, national law or local regulation. For example, in Argentina, Australia and Canada, provincial or state governments collect a royalty by law from mining companies operating in their state.

Resource revenue transfers: Resource revenue transfers are revenues from oil, gas or mineral companies collected by the national government, then transferred to subnational governments separately from other types of revenue. These transfers can go back to the region where they were extracted—called “derivation transfers”—or be based on regional characteristics such as population, education levels or poverty indicators. For example, in addition to the 13 percent of its oil revenues the government of Nigeria shares with producer states, it shares another percentage of oil revenues with all states based on their population, social development and revenue generation.

Resource revenue-sharing systems can address local claims on natural resources. They can also compensate producing regions for the negative impacts of extraction and promote economic development in resource-rich regions. In Bolivia, Indonesia, southern Iraq, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Nigeria and Papua New Guinea, such systems have also helped to preserve or create a degree of harmony between the central government and certain regions.

However, they can encourage wasteful spending at the subnational level, especially in countries where local governments are not well prepared for sudden, large flows of income or are not responsible for providing expensive public services.

Resource revenue-sharing systems work best when the formula is openly negotiated, appropriate revenue streams are shared and revenues are made predictable. Payments from companies to governments should also be fully transparent, otherwise subnational governments are not able to verify whether they are collecting what is due.→ For an overview of those specific challenges, see NRGI’s primer on subnational revenue management.

-

Corruption risks in the management of extractive revenues

Financial benefits from the oil, gas and mining sectors are enormous. In many resource-rich countries, they form more than half of government income. Sadly, in certain contexts, each of the institutions mentioned here has succumbed to severe mismanagement, and in some cases, outright corruption. Corruption can take many forms, but the result is the same: the country suffers, while a few elites benefit.

Funds spent through the national budget can be diverted to politicians’ preferred projects, or project costs can be inflated, leading to significant losses and poor project selection. For example, Azerbaijan spent its oil revenues on lavish buildings and monuments, such as a $28-million flagpole, yet still pays doctors $300 per month on average.

Sovereign wealth funds, strategic investment funds and development banks can become “slush funds”, meaning they are used to finance the ruling regime or its friends. For example, the Angola fund recently invested $157 million in a hotel complex to be built by a company owned by the fund’s principal asset manager, on land he also owned.

There are even cases of corruption and mismanagement of resource revenue-sharing systems. Studies carried out in Brazil, Colombia and Peru have shown that housing, education, healthcare, and economic growth did not improve following the receipt of large oil or mineral revenues by subnational governments. Diversion of funds away from local budgets, corruption within subnational governments, and the resource curse—when resource revenues push up prices, rather than resulting in more projects and services—have been suggested as explanations for these unexpected results.

Story leads

Research questions and reporting angles

Below are story angles for reporting on financial flows in a particular country, based on a sequence of research questions. See Chapter 1 for more general story planning guidelines.

Coronavirus disclaimer!

-

A. Where is the money going?

1. Find out what revenue your government receives from oil, gas, and mining. Inflows of money can be researched through several sources:

- National sources

Governments usually publish national budgets on the websites of relevant ministries, such as the ministry of finance, or sector-specific ministries. These often show revenue streams disaggregated by source (e.g. oil and gas or royalties). - Extractives Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI)

EITI-implementing countries must publish the annual amount of revenues from extractives. EITI country pages allow users to find revenue data either in the “revenue collection” bar chart or the latest EITI reporting. The revenue data is disaggregated into different streams, including royalties, types of tax, bonuses, license fees, and monies paid to the treasury from state-owned companies. Note that EITI data is generally 1–2 years old. - Natural Resource Revenue Dataset

NRGI compiles a dataset on government revenues from oil, gas and mining originating from the EITI, the International Monetary Fund and the International Centre for Tax and Development. These data allow quick comparisons of figures for total revenues between countries, but do not provide disaggregated information by payment stream. - Project payment data on resourceprojects.org

This website shares information from payments by companies based in the U.K., the EU, Norway and Canada. Data can be searched by company or government entity, and can be useful to track revenues from a specific project, but are unlikely to be comprehensive for a specific country.

Consider the scope of revenues

The scope of revenues may be newsworthy, especially if the amount is particularly big or small in relation to the national budget. While comparisons between countries of raw figures for resource revenues are rarely helpful, a comparison of the portion of resource revenues in national budgets may be of interest in some contexts.2. Check how the government plans to use oil, gas and mining revenues.

- Start with the budget. A budget represents a government’s plan for how to spend (some or most) revenues. To get an idea of how natural resource revenues are spent in your country, seek out the government’s most recent budget and the national development plan, if publicly available. The budget and national development plan are usually published online by the relevant government ministry, such as the budget office or planning ministry. Other ways to find the government’s spending plan, include:

- Using source documents of indices.

The evidence used for scoring on global indices can be helpful to uncover where certain documents are usually published. Country surveys from the Open Budget Index, an index of budget transparency published by the International Budget Partnership, show whether particular budget documents are publicly available and where to find them if so. Question 2.4.1b in the Resource Governance Index (which can be viewed through the Data Explorer ) asks whether a national budget has been disclosed and provides the source document if so. - Reviewing political promises.

Politicians in resource-rich countries often make promises during campaigns about how they plan to spend resources revenues if elected. These promises occur most often in political speeches, but in some countries they are written into party policy documents.

- Using source documents of indices.

- Consider whether there are plans for resource revenues to be spent outside the budget process. National websites are the most likely source of comprehensive information, while the following sources can point towards the best documentation:

- The Resource Governance Index can provide insight into where revenues are dispersed outside the budget. The country profile tool shows whether the country has a state-owned enterprise (SOE), sovereign wealth fund or revenue-sharing mechanisms. The Data Explorer can provide links to government documents for specific countries by looking at questions related to SOEs (question 1.4.1a), sovereign wealth funds (question 2.3.a) or resource revenue-sharing (2.2.a).

- EITI. EITI-implementing countries must include information about how resource revenues are allocated and spent in their annual reporting. This includes noting whether sovereign wealth funds, revenue-sharing mechanisms and state-owned enterprises exist. Although the data is usually two years old, it can provide a starting place for checking for updated figures. EITI reporting is usually available on the national EITI websites or through the international site.

- Consider the proportion of spending within and outside the national budget.

Compare the percentage of total revenues spent within the national budget to those spent through other mechanisms. Stories can emerge from investigating the level of checks and balances, the extent to which the national budget is at risk of volatility shocks, and what level of impact should be expected from the national budget spending. - Consider the gender implications of spending decisions.

Decisions about where to allocate revenues are not always gender-neutral. Many projects benefit men more than women (see Chapter 6). The field of gender budgeting analyzes the gender implications of spending decisions. Reporters can carry out their own investigations or ask gender experts to assess the budget information for gender imbalances as a result of the spending decisions.

3. Check the expenditures. The budget is the plan for spending, but actual expenditure should represent how much money the government spent on particular projects. This can be assessed through several sources:

- Expenditure reports. Governments often provide financial accounting of their actual expenditure. Question 2.1.4c of the resource governance index considers whether and where a country discloses expenditure. Open Budget Index country surveys also provide information about how much a country discloses about its expenditure and where./li>

- Look for impacts. When budgets provide for tangible projects, such as roads, teachers or buildings, reporters can check on progress in realizing those plans. This report from Ghana is an excellent example of a journalist tracking specific expenditures related to resource revenues.

- Monitor transfers. Revenue distributions that are transfers to other parts of government can be monitored by checking that the amount transferred by one institution matches the amount received and used by the next. In most EITI-implementing countries, EITI reporting includes verification of transfers between national and subnational governments. For example, the Philippines’ EITI Report includes information about how much a national government agency transferred to a subnational government and how much the subnational government received, and when. Outside the EITI process, transfers can be checked by comparing municipal budget figures against revenue transfer figures from the national budget. This type of verification can reduce the risk of corruption between different government actors.

- National sources

-

B. Is there enough oversight of how revenues are spent?

The following research steps focus on national-level oversight, but could be applied when revenues are shared subnationally to the local level.

1. Assess how easy it is to find information about government spending of resource revenues. Transparency is a critical first step to proper oversight of how a government spends revenues from oil, gas and mining.

- Consider disclosures checked by indices.

- The Open Budget Index, an index of budget transparency published by the International Budget Partnership, allows for easy comparison between countries, showing their practices for transparency and participation in creating budgets. Note that this analysis considers the national budget and refers to all government revenues, not just resource revenues.

- The Resource Governance Index enables comparisons of how transparent revenue management is across countries. By opening the revenue management tabs in the country explorer, users can see how a country compares to others on particular types of transparency. The Data Explorer allows more advanced analysis that considers how countries compare to regions on specific questions. Particularly relevant questions include 2.1.1a on online data portal coverage, 2.1.4b on budget disclosure, 2.1.4c on government expenditure disclosure and 2.1.5a on debt level disclosure.

- Consider disclosures within international initiatives.

- EITI Validation. EITI-implementing countries are checked, or “validated,” periodically to assess whether they are disclosing information in line with the EITI Standard. A detailed validation scorecard is available on the national and international EITI websites. The scorecard shows whether the country has made progress in disclosure for revenue collection, allocation and transfers. There is a brief explanation for each score.

- The Open Government Partnership (OGP) is an international multi-stakeholder initiative that supports countries in processes of transparency and accountability. Multi-stakeholder groups within member countries set national goals for openness in sectors they prioritize. Often these goals include elements related to transparency of revenue management. Each goal is assessed for its level of completion after the two-year implementation period.

- Consider users’ experiences in accessing information.

A strong picture of levels of meaningful information disclosure can be gained by asking a variety of people who might use information related to resource revenues. This can include formal oversight actors, such as parliamentarians and supreme audit institutions, or informal actors who want to know what benefits to expect from extraction, such as civil society groups and people living close to an extraction site. Interviewing many different types of people can create an understanding of different types of transparency. For example, in many countries, there are differences between the access women and men have to information about budgets.

2. Review the effectiveness of oversight mechanisms for checking on government spending of resource revenues. Transparency of information does not necessarily result in governments being accountable for what that information shows. Reporters can follow up on the extent to which other actors can find accountability for how revenue is managed.

- Identify which public entity is responsible for overseeing public income and expenditures. Multiple institutions may be assigned formal oversight roles, including parliament, a supreme audit institution or an anti-corruption agency. The appropriate oversight institution may vary depending on the source of revenue or the type of revenue allocation. Several sources can show which institution has the power of oversight:

- The Resource Governance Index (RGI). Research explanations and source documents in the RGI can show which institutions have responsibilities for accountability. Use the Data Explorer for the following questions:

- 2.2.4a, on transfer audit requirements, can show which agency audits transfers between government institutions.

- 1.4.3b, on SOE financial audit requirements, considers who conducts and approves a review of SOE finances.

- 2.1.2b, on fiscal rule monitoring requirements, considers which agency, if any, monitors the application of fiscal rules.

- 2.3.5c, on sovereign wealth fund financial audit requirements, shows which agency, if any, reviews how the fund is managed.

- The Open Budget Index, an index of budget transparency published by the International Budget Partnership, shows which agencies review the entire national budget. The “budget oversight” section reviews the extent to which legislatures and auditors are involved in reviewing budgets and expenditures. Each country profile offers recommendations for how oversight could be improved.

- EITI reporting. The narrative of EITI reporting includes a description of a country’s revenue management process. This often, but not always, includes information about who holds responsibility for accountability over different types of revenue.

- The Resource Governance Index (RGI). Research explanations and source documents in the RGI can show which institutions have responsibilities for accountability. Use the Data Explorer for the following questions:

- Consider the independence and resources of oversight bodies. Identifying the role of oversight bodies in theory and practice can help reveal the risks related to extractive revenue management. There are several indicators of an oversight actor’s credibility:

- Legal mandate. What are the roles defined in law of the oversight actor and their mandate to hold others accountable? This may be available on the actor’s website or within legal documents. Consider using resourcedata.org to search for legal documents related to the extractive industry.

- Personnel. Review whether there are overlapping or related personnel across the oversight actor and the government body responsible for the revenues. Conflicts of interest can arise if people are linked through family, political parties or business dealings. A potential conflict of interest does not necessarily mean there is wrongdoing, but can highlight the need for further investigation.

- Political context. Consider the strength of the oversight institution during this political cycle. Has it been able to hold other actors accountable? Have its findings been reported on and taken into account by others? Have actions been taken as a result?

- Consider informal oversight actors. The strength of informal oversight actors, such as the media, civil society and community members, gives an indication of the level of accountability. Interviewing these actors can help uncover whether and when they have seen accountability for revenue management decisions.

- Consider accountability during announcements. When there are announcements on government decisions about how to manage resource revenues, background research about accountability can provide story angles on the risk or opportunity around the decision.

- Consider disclosures checked by indices.

-

C. If a country has a sovereign wealth fund, how effective is it in creating long-term benefits?

1. Find out whether your country has established a sovereign wealth fund (SWF). Possible sources of information include:

- The Resource Governance Index (RGI) The RGI has a section that scores funds. Question 2.3a shows whether a fund exists. This can be reviewed in the country profile tool or, for more detail, in the Data Explorer. Note that there may be more than one SWF in a country, but the RGI only reviews one.

- EITI. EITI-implementing countries must provide information about whether resource revenues are allocated to funds. They are encouraged to include information about the amounts allocated to those funds and how they are overseen.

- The International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds. There is no internationally accepted definition of a sovereign wealth fund, but the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds offers a place to start. In addition, the American Tufts University published a Sovereign Wealth Funds Report in 2019 with a useful list of SWFs in the annex.

2. Learn about the fund’s objectives. Consider whether the fund was created with a clear objective, such as to even out expenditure, save for future generations or save money for certain types of spending. The following sources can provide insight into a fund’s objectives:

- Legal framework. The laws and policies that created the fund may state its purpose. Searches under Precepts 7 and 8 of resourcedata.org can find the legal documents that established the fund.

- Political context. Funds are often created by politicians who make public speeches stating their intentions. Whether these are enshrined formally in law, the political purpose of the fund can provide insight into how it is managed.

- Consider whether these objectives are consistent with national development strategies. Good practice suggests that a fund’s objectives should be in line with the national plan. Interviewing government officials, oversight actors and civil society analysts about how the two align may create a story on the purpose of the fund.

3. Consider how revenues enter and leave the fund. Many countries establish rules about how and when revenues are deposited (put into) and withdrawn (taken out of) the fund. How these rules are expressed and followed affects how accountable the fund will be. Details of these rules can be found through:

- The Resource Governance Index, which has questions on whether the fund has rules about money entering and leaving the fund, in law and in practice. These can be viewed through the country profile or the Data Explorer (under the “Question explorer” tab).

- For deposits (money entering), see:

- 2.3.1c, SWF deposit rule

- 2.3.2b, SWF deposit and withdrawal disclosure amounts

- 2.3.2d, SWF adherence to deposit rule

- For withdrawals (money taken out), see:

- 2.3.1a, SWF withdrawal rule

- 2.3.2c, SWF adherence to withdrawal rule.

- For deposits (money entering), see:

- Interviews with oversight actors. If the fund is not covered by the RGI, or the RGI data (2015–2016) is out of date for your purposes, consider asking oversight actors for the same information about the rules for deposit and withdrawal, compared with what takes place in practice.

When deviations happen. It can be important to interview different sources about why deviations happen. There may be urgent economic or social needs that require deviation, or it may be that the rule was constructed for a purpose that no longer suits the country’s priorities. Interviewing several sources from government, civil society and outside the country can give a balanced view of these decisions. The same can be true if a rule continues to be followed.

4. Analyze a fund’s performance in terms of return on investment. If invested wisely, funds will attract returns and grow in size.

- Compare performance.One way to assess the financial performance of a fund is to compare its average annual return rate with other sovereign funds, or other investment return rates. If the rates of growth are comparatively low for a country’s resource fund, explore whether the investment is being well managed.

- Check on rules.Many funds have rules about how money should be invested. Again, these rules and how well they are followed can be researched using the RGI, through questions 2.3.3a, on SWF domestic investment rules, 2.3.3b, on SWF asset class rules and 2.3.4e, on adherence to asset class rules.

-

D. If a country has revenue-sharing mechanisms, what percentage of revenues should be shared, and is the money getting there?

1. Find out whether your country has mechanisms for sharing resource revenues subnationally. Possible sources of information include:

- The Resource Governance Index, which shows whether there is subnational revenue sharing, under Question 2.2.a. This can be reviewed in the country profile tool under revenue management or, for more detail, in the Data Explorer.

- EITI. EITI-implementing countries must disclose how and when revenues are allocated subnationally. This includes a description of the rules for subnational allocations, as well as figures for subnational transfers made and received.

Understand the revenue-sharing rules. Rules for revenue sharing vary greatly between countries. Several key questions need answering in order to track resource revenue sharing:

- What percentage of revenue is being shared? The percentage figure often grabs headlines quickly, but audiences will only accurately understand what is due to the local community if they also know the answers to all of the questions in this list.

- What revenue is being shared? Different resource revenue streams, such as royalties, taxes or production shares, may be shared differently. To understand revenue-sharing obligations, each revenue stream must be explained separately in terms of the percentage that should be shared.

- Who is it being shared with? Countries often have multiple layers of subnational government. It is important to understand which government body or community group will receive the revenues. In some countries, the municipal body in a resource-rich area receives a different amount from the provincial government.

- What is the timeframe? Countries vary as to whether revenues are shared quarterly or annually. This can make big differences in local-level planning.

- Are there any restrictions on spending? Some countries put restrictions on the types of projects or services local governments can fund with shares of resource revenue.

- Sources: The questions above can be addressed by reviewing the following:

- Legal framework. National laws and regulations should clarify revenue-sharing rules, both through sector-specific law (e.g., mining law) and laws that define the relationship between local and national governments (constitution, intergovernmental transfer legislation, presidential directive, etc.). Searching resourcedata.org under Precepts 5 and 7 should reveal some of these laws and policies.

- EITI. EITI-implementing countries must disclose how and when revenues are allocated subnationally. This includes a description of the rules for subnational allocations, often referring to the legal framework.

Consider the implications. There is often confusion about what revenues are being shared, at what rate, with whom. Once this is clarified, it can be revealing to interview different stakeholders about whether the legal reality meets with their expectations. Sample calculations can show the relative size of revenue shares compared to budgets or other revenues, giving context for debates about whether revenue-sharing arrangements are fair.

2. Monitor transfers. Laws about revenue sharing do not necessarily result in consistent revenue sharing across all local governments for all extractive projects. Monitoring some transfers can help clarify what local governments should expect.

- Double verify. Monitoring transfers involves asking those who made a transfer (usually the national government) and those who received it (usually a local government) what they paid or received, and when. Comparing these figures shows whether the revenues are flowing as expected.

- Check figures against calculated expectations. When a figure such as the total royalties from a project, is available, it is possible to use the revenue-sharing formula to calculate the expected transfer amount. Comparing the expected amount with actual transfer figures can be the basis for a story.

- Sources:

- National and local budgets. Depending on levels of transparency in a country, it may be possible to see resource revenue allocations in the national budget and receipts in the local budget.

- EITI. EITI-implementing countries must disclose how and when revenues are transferred subnationally. This includes figures for the actual transfers and subnational receipts.

- Resourceprojects.org collects information about payments from companies to various government entities, based on where the company is listed in stock markets. This often results in detailed information about a project, though rarely in comprehensive information for an entire country. The data are helpful in calculations to verify whether the revenues shown in budgets match expectations based on company payments of a particular revenue stream.

Examples of good reporting practice

The examples given below can provide inspiration while preparing stories on revenue management. Some highlight day-to-day reporting, while others are in-depth investigative reports.

-

Conflict over sharing of Iraq’s oil revenues (day-to-day)

What is the fate of Baghdad-Erbil’s oil-for-budget agreement amid ongoing protests?

This article in the regional online paper, al-Monitor, analyzes how political changes in Iraq may impact ongoing budget and oil revenue-sharing debates. Published after the Iraqi Prime Minister’s resignation in 2019, the article explores how the resignation affects a deal about oil revenue sharing between the national government and the regional government in Kurdistan. It provides a strong example of how to incorporate issues about oil revenue management into day-to-day reporting of political changes. As well as explaining political issues with quotes from multiple parties, the article shows how poor resource revenue management has left citizens without expected services. By describing absent infrastructure and putting large figures into context, the article helps the audience understand the importance of these negotiations for people in Kurdistan. It could be strengthened by providing credible sources to back up allegations of corruption.

-

The challenge of managing revenues from a finite resource in Timor Leste (day-to-day)

Time (and Oil) Running Out for Timor-Leste.

Published after parliamentary elections in Timor Leste in July 2017, this story from a regional publication, The Diplomat, discusses how the results are linked to ongoing debates about managing oil revenues during an expected decline in oil production and revenues. The story works well because it uses the elections as a hook to explore more fundamental questions around the management of oil revenues. It explains at the start the key issues and provides readers with relevant facts and figures, quoting many different sources to offer a balanced view.

-

Oil money gone missing in Angola (investigative)

How western advisors helped an autocrat’s daughter amass and shield a fortune.

This joint investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and 36 media partners carefully shows how Isabel dos Santos, Africa’s richest woman and the daughter of a former Angolan president, stole hundreds of millions of dollars—including from Sonangol, an Angolan national oil company. Rather than focus on the angle of African corruption, the reporters used a wealth of leaked documents to show how western accountants and consultants helped legitimize dos Santos’s empire, and how weak western regulation enabled this. Although the central report is over 4,000 words long, the authors provide the key messages at the top of the article and give a visual explainer, a three-minute video and a data explorer.

The strength of this deep investigation lies in placing a familiar story of corruption within the transnational system that enables it.

-

Missing impact from Ghana’s oil revenues (investigative)

Documentary series on projects funded by Ghana’s oil money.

This excellent series of documentaries by the Ghanaian national media outlet, JoyFM, illustrates gaps in realizing the benefits of Ghana’s oil wealth. The documentary, “Leaking Oil,” tracks Ghana’s oil income to find out that money is often wasted through inflated project costs due to delays and poor execution and maintenance, including projects for various roads.

After several months of investigation and filming, the journalist offers a vivid account of oil expenditures, using documentary sources to put his research into context. He interviews different sources, including citizens unable to benefit from the planned infrastructure, contractors and civil society representatives. This gives the story strong human interest, in contrast with the factual topic of the Petroleum Management Act.

See also below the “Behind the scenes” story by reporter Stephen Nartey of how he covered this story.

-

Behind the scenes of Ghana’s oil money: Testimony by JoyFM reporter Kwetey Nartey

This podcast gives an account by journalist Stephen Nartey of how he developed and researched his coverage of Ghana’s oil spending. The documentary, “Leaking Oil,” tracks Ghana’s oil income to find out that money is often wasted through inflated project costs, due to delays and poor execution and maintenance, including projects for a school, a dam and various roads.

Transcript

Full transcript

My name is Kwetey Nartey, I’m an investigative journalist from Ghana, and I’ll be talking about how I tracked oil monies, from starting with scanty data to getting everyone talking about how the government had utilized the country’s oil revenues over the last decade.

When your government claims it’s using oil revenues to the benefit of the citizenry, it gets you wondering, why are the beneficiaries of these projects not being heard or talking about it? Like individuals such as Osman Ibrahim, a former Assembly member of Nakore in the Upper West region of Ghana. Eleven years ago, the government awarded a contract of over $160,000 to a contractor to rehabilitate an irrigation dam in this community.

In many instances, the implementing authorities will present data suggesting oil projects have been completed. Don’t believe this as a reporter yet, go to the ground and check whether it is accurate. And that is what this project of “Tracking the Oil Cash” sought to do. The findings were immensely amazing, because I found out the authorities – the Irrigation Development Authority – was peddling untruths.

This presented an opportunity to explore the bigger picture of what the situation was across the country. I started this project by first researching on what existing data was available. I found some work that had been done by the Public Interest Accountability Committee – a supervisory body that has oversight responsibility for how the government utilizes oil revenues. No one had acted on their report, even though the findings were revealing, as explained by the Committee Chairman Dr Steve Manteaw.

He gave me further insights on how these oil monies have been misappropriated, but, as has been the case, the government was indifferent towards the details.

The task ahead was daunting given the millions of dollars that had been pumped into oil projects across the country. What I did was to list and plot similar projects across eight regions. The next thing I did was to identify the communities where these projects were sited and the institutions/individuals who were awarded the contracts. This process of plotting the project on what I would describe as investigative scoreboard made it easier to track my own progress.

What was critical, though, was that I needed evidence. I relied on local networks, like local reporters and opinion leaders when I visit the communities. These individuals facilitated my transportation and aided in identifying where I could speak to the persons that mattered. It explains how I was able to connect with motor riders who took me to reach communities, and opinion leaders opening up to me.The fundamental tips are:

– Relate to the townsfolk, establish a means of communication, find the opinion leaders. They will be your map to identify the projects and those affected by them.

– After I completed gathering the evidence, I approached government agencies and institutions who were supposed to act on it. Sometimes, these agencies will not give attention to your work. Don’t be deterred, go ahead and publish your findings. They will come running later begging to be heard. For instance, I approached the Irrigation Development Authority on this project. They ignored me. But when the story started gaining currency, they were calling me every day simply to give their side of the story.

– In terms of the broadcast strategy I used with this project, I used a multimedia storytelling approach. The story was on TV, radio, online and all social media platforms. So if someone missed the story on TV, they would hear it on the radio or read it on social media.That’s what got the story to make impact. And by impact, I mean, the supervisory body PIAC has signed a Memorandum of Understanding with me to join forces to track oil money. One of the biggest oil companies, Tullow Ghana, is looking into the issue. Some of the road contractors who had done shoddy jobs issued statements explaining what had transpired.

That’s how “Tracking the Oil Cash” became a success.

Sources

Below are sources that can contribute to different angles on stories about revenue management. Some will be similar across different aspects of mining oil and gas reporting and are repeated across chapters, but others apply specifically to revenue tracking. When possible, there are direct links to institutions in the main target countries of “Covering Extractives”: Ghana, Myanmar, Tanzania and Uganda.

Coronavirus disclaimer!

-

Public institutions

Government entities

Administering revenue from oil, gas and mining usually involves different government players. The bodies involved in collecting and spending revenues vary between countries, but can include ministries of finance, budget or planning; state-owned enterprises; sovereign wealth funds; the central bank, or subnational governments.

EITI-implementing countries offer overview of the ministries involved in revenue management in the narrative section of their EITI reports. The Resource Governance Index country profiles usually include the key ministries involved. Contacting staff at different government entities can help bridge information gaps and provide a useful perspective, but it is important to assess any information received and verify it with further sources.

Below is a list of websites to access for these different government entities–ministries, central banks and SWFs–in the “Covering Extractives” target countries:

Ghana

- Ministry of Finance

- Ghana has two SWFs, the Ghana Heritage Fund and the Ghana Stabilisation Fund

- Bank of Ghana

Myanmar

Tanzania

Uganda

- Ministry of Finance

- Uganda’s SWF, the Petroleum Revenue Investment Reserve

- Bank of Uganda

Oversight bodies

In most countries, parliament is responsible for approving the annual state budget. It also adopts the rules that apply to spending and distributing resource revenues. In Uganda, Parliament must review the national budget by 31 May each year. In Ghana, in addition to the parliamentary budget committee, the Public Interest Accountability Committee also reviews the spending of oil revenues. The committee’s bi-annual reports show how revenues were spent, and are a useful source for journalists following the impact of resource revenues.

Supreme audit institutions also provide important oversight of whether resource revenues have been allocated and spent according to the rules. Their mandates allow them to investigate public spending at various levels of government, and their reports offer valuable insight into the effectiveness of resource revenue management. For example, the Supreme Audit Institution of Ghana conducted an audit reviewing the management of the country’s Petroleum Fund, while the Auditor General of Niger reviewed all national oil revenues. -

Experts, civil society and watchdogs

National groups

Experts from civil society and academia can be helpful commentators on revenue management. They can distance themselves from government or company interests, and offer a different view of what is in the people’s interest.Where relevant, journalists are welcome to contact the NRGI country offices, where staff can provide connections with the right expert internally.

Other options for connecting with competent civil society or academic figures include:

- Publish What You Pay (PWYP), the global coalition of civil society organizations campaigning for a fair use of natural resources. PWYP has over 700 member organizations in 50 countries, working on numerous issues, including revenue management. Its national coordinators are able to direct journalists to a range of expert contacts.

- In EITI member countries, there will be civil society representatives on the national multi-stakeholder group. The national secretariat can also offer recommendations for civil society groups that specialize in revenue management.

- The International Budget Partnership (see below) usually contracts a national civil society group to conduct the analysis for its Open Budget Index. The group involved in the index for a country is likely to be familiar with the overall national budget process and may also be able to provide information on extractive revenue management.

International civil society

Many global transparency efforts have their roots in revenue management. The International Budget Partnership promotes transparency and accountability in budget processes. Although its programs are focused on a few countries, many of its resources and analyses are applicable in others. Oxfam America, another international NGO, is well known for its advocacy on extractive budget and revenue transparency. It has also recently produced work that gives insight into how women can most effectively be engaged in revenue management to reduce the gender gap associated with extractive impacts (see Chapter 6). Contacting experts at these organizations can give context and credibility to national reporting. -

International institutions

International financial institutions

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank produce regular guidance on fiscal and economic policies. They also often monitor national revenue management and produce regular analysis of national economies, which can be useful background in national reporting. For example, the IMF produces “Article IV” consultations that assess an individual country’s economic health and often comment on its revenue management. Reporters can sign up on these organizations’ websites for alerts when particular country reports are published. Publications often include the email addresses of staff involved in the analysis or press contact information for follow-up questions.Multi-stakeholder initiatives

The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) is a multi-stakeholder initiative that supports transparency in resource-rich countries through an international standard implemented by members. EITI-implementing countries are required to annually disclose extractive revenues paid, transferred and collected. This includes an overview explaining which ministries collect which revenue streams, as well as a comparison of the figures that government agencies state they collected and what companies say they have paid. These figures can be used to understand overall government revenue and where challenges with revenue collection may lie. The report also outlines information about how revenues are used, and details revenue sharing to subnational governments when appropriate. Although EITI data is often published slowly, the descriptive reports and the types of information available can be used as a basis for asking questions of ministries for more current stories. The national multi-stakeholder group that oversees a country’s EITI process can also be a source for discussions on what information about revenues should be available.The Open Government Partnership (OGP) is an international multi-stakeholder initiative that supports countries in processes of transparency and accountability. Multi-stakeholder groups in countries that have signed up to the initiative set national goals for openness in sectors they prioritize. Many OGP countries have included commitments related to budget transparency or participation, sometimes focusing on the use of resource revenues. Reporters can follow up with national OGP committees.

-

Data sources

Revenue payments

Resourceprojects.org compiles revenue payments made by extractive companies based in the EU, Canada, Norway and the U.K. to host governments. The data are released through companies’ stock listings and are regularly added to the site. Payment information can be filtered by individual project and by government entity. NRGI has also prepared two briefings to showcase how the data can be used when deeper analysis is applied. One covers gold mining revenues in Ghana and the other, oil and gas revenues in Nigeria.EITI member countries are required in their annual EITI report to provide information about income from the extractive sector and how it is distributed. The reports are available on national and international EITI websites.

Budget performance

The International Budget Project publishes a survey analyzing the openness of budget practices in 115 countries. Data from the survey can be found online, with easy views for comparison, or downloaded and analyzed. A questionnaire for each country also provides source documentation to allow easy follow-up research.

Voices

In the short videos below, a company representative from Repsol, a member of Congolese civil society and a government official from the Philippines share their perspective on the management of oil, gas and mining revenues.

Learning resources

-

Video overviews

In this 11-minute video, petroleum economist and Ghana’s Deputy Minister of Energy, Mohammed Amin Adam, describes challenges that come with managing revenues from oil, gas and mining. He also explains some of the measures governments can take to respond to these challenges in this 16-minute video.

Further NRGI videos on managing extractive revenues include one on natural resource funds and another on revenue sharing:

UNU-WIDER has produced several short videos discussing how best to invest extractive revenues for long-term benefit. This two-minute video discusses how to invest the revenues in assets above the ground, and this three-minute video looks at long-term versus short-term investment strategies.

-

Key reports

NRGI has several primers that summarize resource revenue management issues in plain language, including an overview on revenue management, revenue sharing and resource funds.

There are also useful longer reports that draw comparisons between country case studies:

- NRGI and the United Nations Development Program looked at different ways governments in resource-rich countries allocate resource revenues to different levels of government, different institutions or directly to citizens. The resulting report presents key lessons from 30 case studies.

- NRGI worked with the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment on a survey of natural resource funds across 40 countries. In addition to reporting lessons of good practice, there are country profiles on numerous resource funds, explaining the rules that govern those funds.