State-owned enterprises

State participation in the sector

Download the full chapter in PDF

Why it matters

Why does this matter to your audience?

- State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) control very large amounts of oil, minerals and gas. Nationally owned oil companies produce more than half the world’s oil and gas.

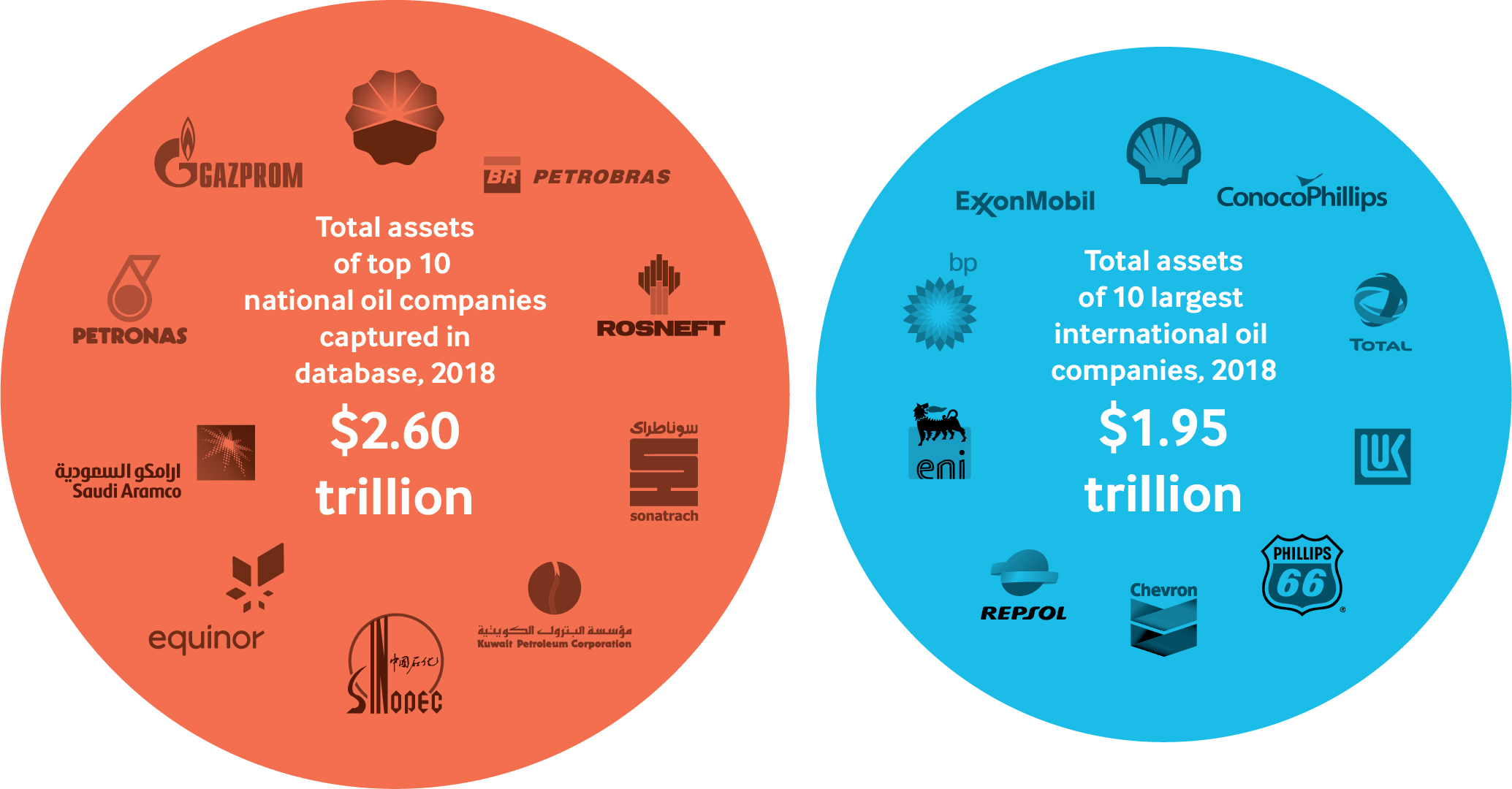

- SOEs control significant sums of money. The combined total assets of the top 10 national oil companies were USD 2.6 trillion in 2018—over half a trillion U.S. dollars more than the combined assets of the top 10 international oil companies.

- SOEs often control a high proportion of money within a country. In at least 25 countries, national oil companies collect revenues equivalent to more than 20 percent of the government’s total revenues. In places like Venezuela, Malaysia, and Kuwait, the national oil company collects more revenue than the rest of the government combined. This often means that they have extensive power in areas beyond oil, gas, and mining.

- A number of SOEs have been the source of huge corruption scandals in resource-rich countries. For example, the Brazilian national oil company Petrobras was at the heart of allegations that billions of dollars in illegal payments had been made to company executives and political parties.

- State-owned companies are often a major source of national pride and have a big impact on the national economy. In some instances, such as in Chile and Saudi Arabia, SOEs have been used to create high-value jobs. In other countries, they are involved in a wide array of industries, ranging from selling insurance to building hospitals and running schools.

The basics

Governments in many resource-rich countries try to increase their revenue and their control over the oil, gas or mineral sectors by creating a company focused on natural resource extraction. Government-owned companies, usually called state-owned enterprises (SOEs), tend to be industry specific. Some countries have one focused on mineral extraction and another for oil and gas usually called a national oil company (NOC). This overview will discuss the different roles SOEs can play in a country, and their potential benefits and challenges.

-

Roles of SOEs: The range of company responsibilities

Governments can create companies focused on extractives that have several different roles, including commercial responsibilities, regulatory responsibilities, policymaking and national development. In many countries, an SOE’s work cuts across several of these categories.

Commercial roles: Acting like a private company extracting and selling resources

Some state-owned companies choose to act like a private oil or mining company and directly participate in the exploration, development and production of an oilfield or mine. In some cases, the SOE will manage the project alone or will be the lead operator in a partnership with other companies. In other cases, the SOE plays a secondary role in the management of a project. Often these companies own a percentage of a project with one or more private partners. When this happens, the SOE is usually entitled to a share of the project’s oil or mineral production, a share of profits the project generates, or both.When an SOE is acting like a private company, it may take on some of the risk of the project. This means the SOE must pay money upfront and will not get the money back if exploration is unsuccessful. In some cases, the SOE’s risk is “carried” by its partners, meaning it does not have to pay a share of upfront costs for unsuccessful projects.

The level of SOE involvement in a particular project varies based on country and project. For example, the Ghana National Petroleum Corporation (GNPC) is usually the minority partner in oil projects in Ghana, while Saudi Arabia’s Aramco usually runs projects alone. Some SOEs apply their experience in the extractive industries at home to participate in exploration and extraction in other countries. Petronas, a Malaysian state-owned company, has extensive reach throughout Africa and Asia.

Covering NOCs’ commodity trading activities

Read moreIn many oil-producing countries, the national oil company (NOC) sells large quantities of oil and gas. This oil and gas comes from the NOC’s upstream activities (the oil and gas the NOC produces itself), the government’s share of a partnership (joint ventures or production-sharing contracts), or in-kind payments made by private companies.

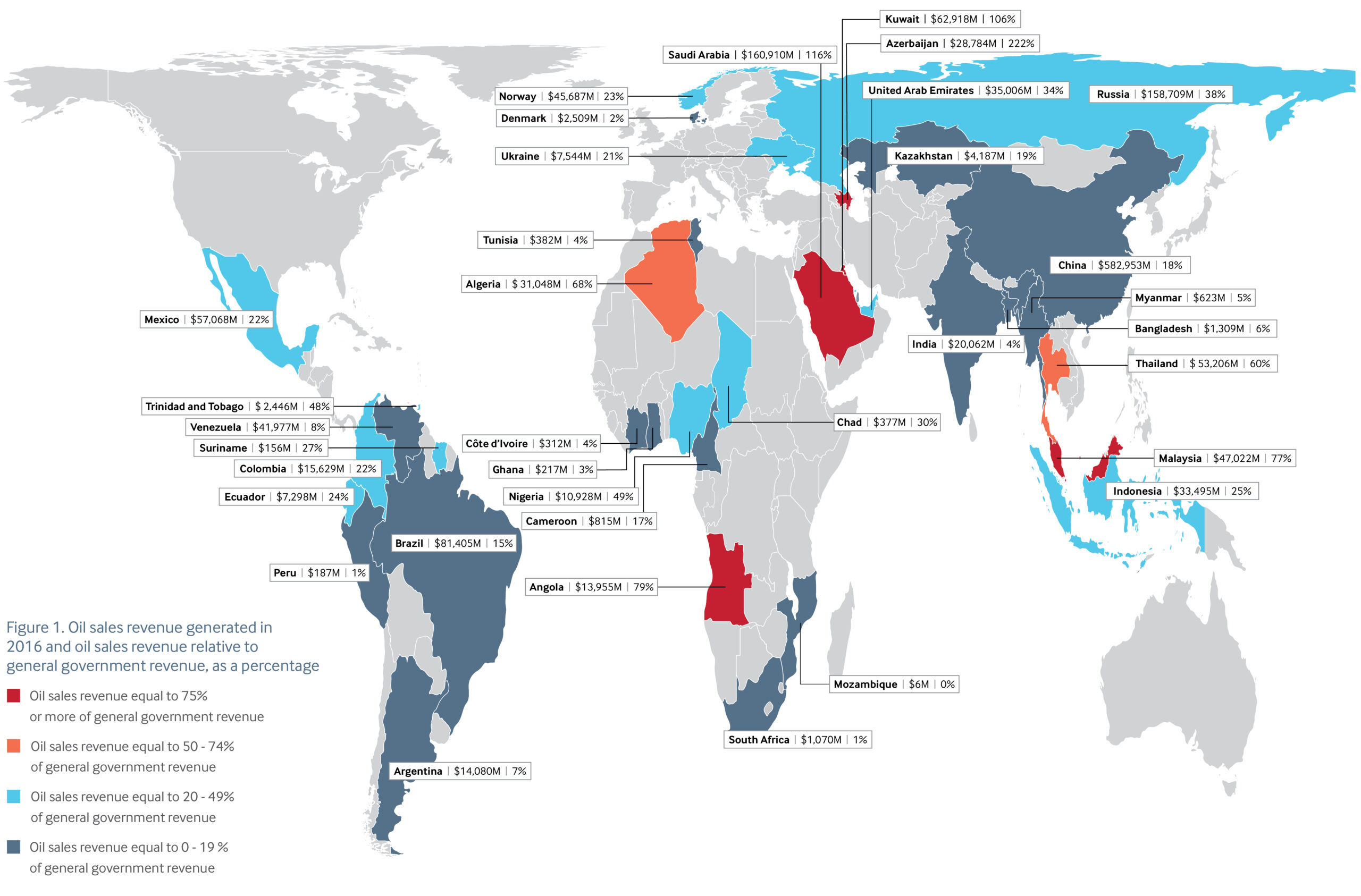

For many NOCs, commodity trading is the way the company makes the most money. In 2016, oil sales revenue made up 95 percent of the total revenues of NOCs analyzed by NRGI in 35 countries. This often translates into important revenue for the government. For example, in Nigeria, oil trading represented more than 50 percent of the government’s total revenue in one year.

Oil sales revenue generated in 2016 (Source:NRGI) Despite the vast sums of money involved, commodity trading is largely secret, creating corruption risks. Very few NOCs disclose detailed information on the buyers, volumes and prices of individual sales of oil and gas. Only three commodity traders—Trafigura, Glencore and Gunvor—disclose the payments they make to governments for the purchase of oil and gas.

Regulating roles: Making and enforcing the rules

SOEs often have a role setting or enforcing the rules of a country’s extractive sector. This can include tax collection, assignment of operating rights, monitoring and management of cadastres, setting rules governing performance, ensuring corporate compliance, and approving company operation plans.Sometimes one part of an SOE will regulate another part of the same SOE. For example, in Malaysia, Petronas both extracts oil and regulates extraction across the country’s oil sector. In contrast, Mexico’s Pemex is regulated by separate agencies, the National Hydrocarbons Commission and the Energy Regulatory Commission.

Quasi-fiscal roles: Spending money to build things or deliver services

Instead of transferring their revenue to other parts of the government, several SOEs directly provide services to citizens. Projects funded by SOEs are often called quasi-fiscal expenses, and can range from building or maintaining roads to promoting health and education, providing consumer fuel subsidies and purchasing arms. This role can create corruption risks, because it involves spending outside the normal checks and balances within budget processes. Angola’s Sonangol, for example, spent more than $27.3 billion over three years on quasi-fiscal projects, such as housing, railways, shipping, aviation and other infrastructure. All this spending took place outside Angola’s usual budget process involving the treasury. -

Why have an SOE? Benefits of SOEs in extractives

Financial benefits: making more money for the government

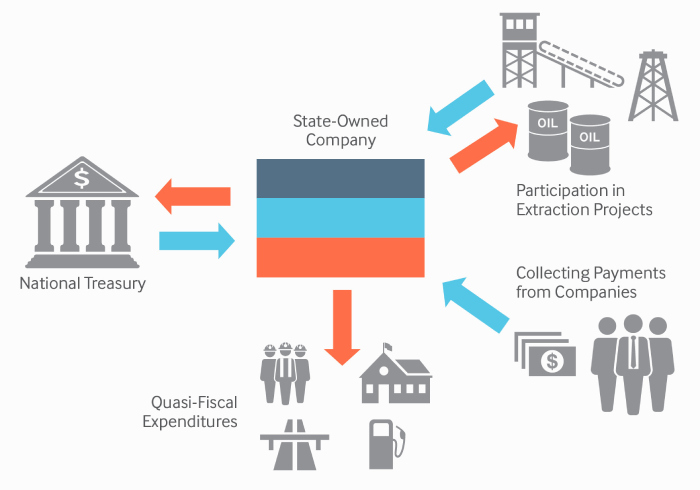

Many countries look to their SOEs as an opportunity to generate public revenue from extraction. Without an SOE, the state derives revenues from its natural resources via taxes and royalties from private companies. SOEs can create additional opportunities to earn revenues by giving the state a share of profits as an operator. The infographic below gives an overview of revenues that flow to and from an SOE:

SOEs and money flows. (Source: NRGI) Workforce development: Creating jobs and expertise in a new industry

SOEs can be key tools to create expertise and high-paying jobs in the country. Many governments require their SOEs to become centers of technical expertise, with the idea that the technologies and approaches they develop can be used elsewhere in the economy. The challenge is that there are often very few jobs in the extractive sector and they require a high degree of specialization.Increased monitoring and fostering of local content

In countries where SOEs engage in joint ventures with private companies, SOEs are viewed as a way of having a seat at the table to better monitor what private companies are doing. Timing the pace of exploration and extraction according to national macroeconomic goals—such as building national capacities before extracting large quantities of minerals—can be difficult for a government that works mainly with private companies driven by market considerations. In Algeria, Malaysia and Saudi Arabia, NOCs have each decelerated oil production at certain times to maximize revenue, save some resource production for future generations or mitigate the effects of the resource curse.SOEs are also seen as strong drivers of local content. Because they can focus on a broad national mandate rather than short-term profits, SOEs can prioritize involving local workers and suppliers in a way that purely profit-driven private companies may not.

-

Performance and oversight challenges

Revenue and “Parallel Treasuries”: Spending outside the regular protections

While most SOEs generate income, they are also big spenders. Many spend on company operations and quasi-fiscal activities, such as schools or roads. The size of SOE spending can create a risk that these companies serve as a de-facto parallel treasury. For example, Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprises (MOGE) is among several of Myanmar’s SOEs that seem to be moving billions of dollars into bank accounts not subject to the regular annual budget process. This could have a big impact on the government as a whole, as MOGE accounts for 16 percent of government oil revenues and 10 percent of expenditure in one year.NRGI data reveals that most of the 71 NOCs in the National Oil Company Database transfer less than 25 per cent of their gross revenues to the government, spending the rest on their operations and investments. If this spending results in long-term benefits to the country, it can achieve value for money. However, spending can also be wasted in the absence of proper oversight. In Ghana, for instance, Parliament ordered the national oil company GNPC to stop its annual sponsorship of $3 million to the Black Stars football team in 2017. This followed a report by an independent oversight body, the Public Interest and Accountability Committee, which found GNPC’s spending to be outside its core role.

Opaqueness: Secrets about revenues, spending and rules

Many SOEs suffer from an extreme lack of public transparency. More than 65 percent of SOEs scored “weak,” “poor” or “failing” grades for transparency of revenue and operations in the Resource Governance Index. Where SOEs disclose such little information, it can be difficult for citizens and oversight actors to know how well they are managing the industry and public revenues.One way for SOEs to combat a lack of transparency is through public reporting. This means having systems in place to ensure that actors meant to monitor an SOE—such as parliamentary committees, regulatory departments or legislative bodies—have access to comprehensive, reliable and regular data on SOE finances and operations.

Risk of Corruption: Lack of oversight

In recent years, several SOEs have been at the center of some of the biggest corruption scandals in natural resource extraction. An investigation called “Operation Carwash,” begun in 2014, revealed that Brazil’s Petrobras conspired with a group of subcontractors to massively overpay for services, leading to billions of dollars in losses for Brazilian taxpayers. For years, the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation sold large portions of the country’s crude oil production to unqualified companies, often referred to locally as “briefcase companies”. These small, little-known intermediary firms—typically connected to a political heavyweight—lack the financial and operational capacity to sell oil. Instead they re-sell, or “flip,” the oil they receive to larger, more experienced commodities traders, and collect a margin on the sale—sometimes to the benefit of Nigerian and foreign politically exposed persons (PEPs). This resulted in significant revenue losses for the Nigerian state.Corruption risks include large amounts of revenue being managed, the political power of the institutions involved and the lack of oversight. One tool that can check corruption is auditing. Audits are independent examinations that verify the company’s figures and information and assess the effectiveness of internal controls. They can be carried out by external companies such as international accounting firms—for example, Ernst and Young or KPMG—or by the national auditing institution.

Debt

Many SOEs carry big debts, either to commodity traders, governments, banks, bondholders or international oil companies. Venezuela’s Petroleos de Venezuala (PDVSA) and Angola’s Sonangol have debt that exceeds 20 percent of GDP. Several NOCs have required multi-billion-dollar bailouts from the state. Namibia, for example, does not even produce oil, yet the state needed to bail out the SOE with $260 million.

Story leads

Research questions and reporting angles

Below are story angles to facilitate reporting on the impact of SOEs in a particular country, based on following a sequence of research questions. More generic story planning guidelines can be found in Chapter 1.

Coronavirus disclaimer!

-

A. Are the roles the SOE in my country plays risky?

1. Find the SOE you want to research.

- Country profiles in the Resource Governance Index (RGI) provide the name of SOEs for each sector, when they exist. Information about the SOE’s disclosure policy and practice can be found under the “value realization” section in the RGI country profile. Note that in some countries there is more than one SOE in the same sector and the RGI chooses just one to asses.

- The NOC database will display the major SOEs for a given country. When a country is selected, a drop-down of different company names will appear.

2. Find out the roles the SOE plays in a country. Three sources provide useful starting points to investigate the role of an SOE: RGI questions, SOE websites and the laws that govern the SOE.

- RGI questions: The RGI country profile provides a text description of an SOE in a country, based on RGI questions. The Data Explorer, which can be downloaded, provides the research answers for each RGI question and links to the source documents. The following questions cover whether SOEs play specific roles: non-commercial activity (question 1.4.4 a), non-commercial spending (question 1.4.4 b), production value disclosure (question 1.4.6 a) and sales volume disclosure (question 1.4.6 b).

- SOE legal documents and disclosures: Resourcedata.org has a large collection of documents that back up the answers in the RGI and data in the NOC Database. The site allows users to filter by country and precept (in this case, Precept 6: Nationally Owned Resource Companies). Documents that might be useful include:

- Annual reports. These provide an overview of what the company says it did over the last year, often including a description of roles, responsibilities and activities. Annual reports are usually available on a company’s website, or at resourcedata.org. If the company is listed on a stock exchange, its annual reports may also be there.

- EITI reporting. EITI-implementing countries are required to include a description of their SOEs and the laws that govern them in their EITI reporting. There are often disclosed through EITI reports, which are likely to be available on the global EITI website.

- Laws. An SOE’s roles are usually defined in legislation or policy documents. In particular, legislation or documentation around the time of an SOE’s creation may provide information about its purpose and mandate.

- The company website. Descriptions on the website of an SOE’s departments, such as regulation, commodity-trading or downstream, could provide leads about its different roles. Many SOE websites also provide links to foundational legal documents and annual reports.

3. Investigate the risks of those roles.

- Consider transparency. An SOE’s transparency in fulfilling these roles can be revealed by:

- Checking for disclosures. The NOC database shows how many key financial and operational data points the NOC makes public. This can be followed up by asking staff at the SOE why certain data is not disclosed and whether there are risks associated with sharing (or not sharing) that information.

- Comparing with other countries. The RGI “Compare Countries” tool enables comparison of a country’s SOE disclosure performance against those of other countries, while NRGI’s Guide to Extractive-Sector State-Owned Enterprise Disclosures provides examples of good practice. This information can show whether a country is doing better or worse than its neighbors. It can also be helpful to ask SOE oversight actors whether they know how other countries do in comparison, and how they explain other countries performing differently.

- Consider oversight. The different roles performed by an SOE may have different oversight actors. Identifying whether the SOE oversees itself or there are clear lines of oversight—and how these differ from oversight of other government activities—can help explain the risk associated with some SOE roles. The following may be useful in identifying oversight:

- Audit. RGI question 1.4.3b provides explanation about an SOE’s financial audit requirements. Finding out which institutions are involved in those audits can show the level of oversight.

- Parliament. Parliamentary committee lists should describe which committees in parliament have oversight of an SOE. If the SOE is legally required to report to parliament, RGI question 1.4.3c can provide insight into when and which part of parliament must receive reports from SOEs.

- Regulator. Consider whether there is an independent ministry within the government tasked with providing oversight of the various roles of the SOE.

- Consider potential conflicts of interest. The extent to which the SOE plays overlapping roles can increase the risk of conflicts of interest—for example, if an SOE allocates licenses that it also competes for, or self-regulates safety and environmental protection. RGI questions 1.4.10a on an SOE’s code of conduct and 1.4.10b on the independence of an SOE’s board of directors can offer insight into conflicts of interest.

- Consider mandate and size.

- Compare with other countries. The NOC database allows comparison between an NOC and one in a neighboring country or with comparable oil reserves. The “Explore by indicator” page offers a range of indicators that can be compared across different NOCs. Different filters can be applied to narrow a search, for instance, to a specific timeframe, region or set of companies.

- Contextualize. This can be done by considering whether the roles intended for the SOE match the likely scale of the industry in a country. How big is the revenue the SOE manages compared to the overall budget? How involved is the SOE compared to the size of the sector and its level of experience?

-

B. Where does the SOE’s money go?

1. Find out the SOE’s revenue.

Several sources offer information about how much an SOE says it collects in revenue and has in assets:- NOC Database. The NOC database company page has a “Revenues” tab that shows the total revenues the company collects. Note that this database is not comprehensive, but includes the major players.

- Annual Reports. These provide an overview of what the company says it did over the last year. They can often be found on the company website or by searching online. The reports usually have a descriptive section and a financial reporting section which should detail the revenues collected.

- EITI reporting. EITI member countries must publish information about their SOEs’ revenue in the annual EITI reporting. Reports are shared on country websites or the international secretariat’s country page. EITI reporting can be searched for the name of an SOE. Note that EITI reporting often reflects data that is two years old.

2. Track how much of the revenue the SOE says it retains or transfers. Data sources offer insight into how much revenue stays in the company, how much goes to other parts of government and how much is spent:

- NOC Database. If a company is in the NOC database, the “transfers to government” tab shows whether there is information about how much has been transferred to different parts of government. The “expenditures” tab should show how much the SOE has spent. Source documents for this data can be found at resourcedata.org.

- EITI and annual reports. The company’s annual reports and EITI reporting can show whether information is published on transfers to the government. SOEs in EITI-implementing countries have to report their quasi-fiscal expenditures. As a result, money they spend on public social expenditure, such as payments for social services, public infrastructure, fuel subsidies and national debt servicing, should be available.

- RGI Explorer. Question 1.4.1a and 1.4.2.a and b will reveal information about any legislation that requires transfers between the SOE and other areas of government. The explanation and background material related to this question give further insight into SOE financial transfers and expenditures.

3. Analyze or monitor transfers and expenditures.

- Compare expenditures with business roles. Consider the rationale for expenditures. Does the SOE pay for things that another part of government would normally cover (such as repaying debts or buying the president an airplane)? Is the SOE involved in politicized spending that benefits the administration in power? Based on this understanding of expenditure, interviews with human sources can support reporting on the rationale behind the spending.

- Monitor the impact. Expenses outside core extractive activities (like owning a football team or managing a hospital) can be tracked in a similar manner to traditional budget tracking. Reporters should look for formal audits or conduct an investigation of impact.

- Formal Audits. Formal audits of spending should reveal information about whether expenditures are reaching their intended goals. Question 1.4.3b on the RGI helps show whether formal audits are required and whether they are made public. In addition to audits done by the SOE, a national supreme audit institution may also conduct periodic audits of revenues and expenditures of government agencies.

- Budget tracking investigation. Expenditure data points can be compared against direct observations and multiple source interviews that assess impact. This requires combining site visits with interviews about expected and actual outcomes. This investigation from Joy FM in Ghana shows strong revenue tracking reporting.

-

C. Who is involved in management of the company?

1. Assess corporate governance systems.

- Find out how management of the SOE is organized. Company websites and annual reports usually have sections describing the company organization and how the management team is held accountable. Searching the ResourceProjects.org portal for documents related to the SOE (Precept 6) should reveal the legal framework for how the SOE is organized.

- Check what safeguards are in place to promote effective and accountable management. Corporate policies can be found through company websites or annual reports, detailing the principles that guide the management of an SOE. RGI question 1.4.10a provides information about whether an SOE has a corporate code of conduct and will link to the source documents. If information on policies is not publicly available, it might be found via the SOE’s press office. Reporting on policies can include questioning whether they include strong standards requiring experience and integrity as pre-qualifications for board membership, whistleblower protection for employees who report wrongdoing, merit-based hiring and promotion, and anti-corruption training.

2. Review board composition, competency and independence. Most SOEs are overseen by a board of directors responsible for ensuring that the company delivers against performance targets and objectives set by the government.

- Check who sits on the board. Board composition can usually be found online at a company’s website or in its annual report, or at business press websites, such as bloomberg.com. If the list is not online, call an SOE’s press secretaries.

- Consider independence. The OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises (2015) recommend that boards of directors are free from government interference, to allow for objective and effective oversight of the SOE. Question 1.4.10b of the Resource Governance Index considers whether the majority of an SOE‘s board of directors are independent of the government (meaning at least half of all board members do not hold positions in the current central government). The OECD guidelines outline further principles of good board governance, including conflict-of-interest policies that prevent board members from having any material interests or relationships with the SOE.

- Consider professionalism. To profile board members, the Global Investigative Journalism Network offers a toolbox on researching people and companies’ background. Reporting on the board profile should cover whether members are experienced professionals with expertise in mining or oil and gas, or political appointees with limited relevant experience.

Examples of good reporting practice

The examples given below can provide inspiration while preparing stories on SOEs. Some highlight day-to-day reporting, while others are in-depth investigative reports.

-

SOEs and debt in Myanmar (day-to-day)

Oil and gas responsible for half of Myanmar’s debt

This article published in the national newspaper, the Myanmar Times, covers an EITI Report showing that half of Myanmar’s government debt comes from the oil and gas sector. The story works by being clear, direct and to the point. It gives the main countries and companies to which the Myanmar government owes its debt. The story also calculates how many years it will take Myanmar to pay back its debts at current repayment rates, which can help readers understand the meaning of the large figures. It would be even stronger if the reporter had been able to contact Myanmar’s oil and gas SOE for comment. -

SOEs and subcontracting scandal in Brazil (investigative)

The carwash scandal

This 25-minute documentary by Al Jazeera provides a detailed overview of Operation Carwash, an ongoing investigation into money laundering and bribery by top Brazilian officials and executives at the SOE Petrobras. It uses documents and interviews to explain the massive money-laundering scandal spanning a dozen countries. The film is effective because it gives broad context and specific details about characters and companies involved. By visiting key people and places, including the board of directors in the seaside headquarters of the huge construction company at the center of the scandal, the documentary draws in viewers to make them feel engaged with what happens next. -

Prices of commodity trading in Ghana (day-to-day)

Discounted crude oil sales justified; Finance Ministry erred-GNPC

This article by the multi-media forum Citi Newsroom in Ghana covers the response by the state-owned Ghana National Petroleum Corporation (GNPC) to questions from the Ministry of Finance about how gas was priced in commodity sales. Ken Ofori-Atta, Minister for Finance, questioned why GNPC allowed buyers to choose the lowest possible price when a higher price could have been achieved, costing the state USD 34 million in lost oil revenue. The article is successful in providing space for both the criticism and the SOE’s response. It includes a long video interview with the chief executive officer of the company, asking for responses to specific questions raised by oversight bodies and civil society about the SOE’s operations. Even though it covers very complicated topics, the report does well in providing examples of what is standard in the industry, and using plain language when possible. It could appeal to a wider audience by providing comparisons that related the financial figures to meaningful items in readers’ daily lives. -

Uganda’s SOE and the promotion of local content (day-to-day)

UNOC to invest $840m in oil and gas sector

In this story, the reporter from The Independent looks at UNOC’s plans to ensure Uganda’s economy can benefit more broadly from extracting oil and gas. On the basis of an interview with UNOC’s CEO, he explains how the USD 840 million in announced investments will go towards joint infrastructure projects – refinery, pipeline, storage tank, bulk trading and an industrial park. The story does well in providing readers with additional background and information about the latest developments affecting the extraction of oil in Uganda.

Sources

Below are sources that can contribute to different angles on stories about SOEs. Some will be similar across different aspects of oil and gas reporting and are repeated across chapters, while others apply specifically to SOEs. When possible, there are direct links to institutions in the main target countries of “Covering Extractives”: Ghana, Myanmar, Tanzania and Uganda.

Coronavirus disclaimer!

-

Public institutions

Home country SOEs

Reporters can identify their home country’s SOEs by consulting the Resource Governance Index country profile. While covering a story, it can be helpful to access human sources in several parts of an SOE. The press office should cover general enquiries, but building relationships within specific departments will bring depth to a story. For example, the investor relations department can provide information about corporate governance and financial performance. For insight on financial report releases, it is helpful to interview people responsible for accounting or spending within the company. Many SOEs have a department of strategy or similar division that can be a good source of information on the company’s ambitions and how it sees its role. In EITI member countries, SOEs often have representatives who serve on the EITI multi-stakeholder group, and who may feel a strong sense of responsibility for public engagement and reporting.Oversight institutions

In many countries, SOEs must report to parliament. Although the legislature’s powers of inquiry will vary between national contexts, parliamentarians generally have a mandate to check that an SOE fulfills the mission set out for it in the law. For example, in Ghana, Parliament created the State Interests and Governance Authority to oversee SOEs, including the state-owned oil company. Contacting relevant parliamentary committees and individual parliamentarians can offer insight into how well an SOE is performing. Additional scrutiny is usually provided by supreme audit institutions. For example, the Supreme Auditor of Nigeria conducted a forensic audit looking into the payments between the SOE and the country’s federal states, highlighting billions of dollars of missing money.The ministry responsible for overseeing the SOE, usually the ministry of petroleum or mines, can provide insight into how the SOE’s performance is meeting expectations. For example, in Tanzania, the Ministry of Minerals oversees the State Mining Corporation and the Ministry of Petroleum oversees the Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation. In other countries, like Myanmar, there is less clear institutional oversight of the state-owned company. Beyond sector-specific institutions, it can be helpful to ask ministries responsible for financial management or environmental protection about the roles and actions of SOEs. For example, the Ministry of Environment in Ghana is responsible for monitoring the environmental impact of all extraction, including projects by the state-owned Ghana National Petroleum Corporation.

-

Experts, civil society and watchdogs

National groups

Experts from civil society and academia can be helpful commentators on SOEs. They can distance themselves from government or company interests and offer a different view and analysis of what is in the people’s interest.Where relevant, journalists are welcome to contact the NRGI country offices, where staff can provide connections with the right expert internally.

Other options for connecting with competent civil society or academic figures include:

- Publish What You Pay (PWYP), the global coalition of civil society organizations campaigning for a fair use of natural resources. PWYP has over 700 member organizations in 50 countries, working on numerous issues, including SOEs. Its national coordinators are able to direct journalists to a range of expert contacts.

- In EITI member countries, there will be civil society representatives on the national multi-stakeholder group. The national secretariat could also offer recommendations for civil society groups that specialize in SOEs.

International civil society

International think-tanks that produce research on SOEs include Chatham House, the International Institute for Sustainable Development and the Baker Institute for Public Policy. -

International institutions

International financial institutions

The World Bank often advises governments on their management of SOEs. This can include analyzing the pros and cons of SOE impact on economies and governance. In 2017, the World Bank Group committed not to finance new upstream oil projects, so the bank is unlikely to fund new projects related to upstream work by SOEs. In addition to World Bank country offices, thematic experts based at its headquarters may be able to supply information about how a particular country’s SOEs compare to global standards.Multi-stakeholder initiatives

The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) is a multi-stakeholder initiative that supports transparency in resource-rich countries through an international standard implemented by member countries. EITI implementing countries are required to annually disclose information about any SOE, including the scale of government ownership in companies and the structure for revenue transfers between SOEs and other parts of government. Although EITI data is often published slowly, the descriptive reports and the types of information available can be used to ask questions of ministries for more current stories. The national multi-stakeholder group that oversees a country’s EITI process can also be a source for discussions on what information should be made available about SOEs. -

Data sources

National Oil Company Database

The National Oil Company Database brings together useful information about the finances and operations of 71 NOCs in 61 countries from 2011 to 2017. NRGI will update the data every few years. The content can be searched by company name or by indicators such as number of wells, operational expenditure or income per employee. Data is presented to allow for easy comparison across companies. This article from The Economist is an excellent example of how to use the NOC database, giving a regional analysis of NOCs in Latin America. NRGI has created a short video with information on using the database.

Voices

In the short videos below, a member of Parliament in Ghana, the CEO of the Ugandan national oil company and a civil society representative from Myanmar share their views about SOE performance and oversight in their respective countries.

Learning resources

-

Video overviews

- This two-minute video from UNU-WIDER gives an overview of the challenges NOCs face and some of the steps they can take to be successful.

- In a 12-minute video, NRGI’s Patrick Heller goes into more detail about what NOCs do, how they are most successful and what types of questions can be used to monitor them.

-

Key reports

NRGI has a seven-page plain-language primer on SOEs which gives an overview of the different roles SOEs can play and how they are managed.

Three strong reports on SOEs have been published recently:

- In 2019, NRGI published a report based on the data available in the NOC database. A summary report identifies trends such as the large sums controlled by NOCs and the strong potential they have for impacting a nation’s debt. A more academic version gives detail about the forms of analysis that can be carried out with the NOC database, and some early findings.

- Chatham House has published multiple reports on SOEs, based on close case-study analysis and collaboration with NOCs around the world. This report discusses the financing of NOCs.

- In 2018, the EITI published Upstream Oil, Gas and Mining State-Owned Enterprises, which gives an overview of international reporting guidelines for SOEs in oil, gas and mining. It examines what information SOEs should disclose, when and how.