What’s in the deal

The ins and outs of oil, gas and mining contracts

Download the full chapter in PDF

Why it matters

Why does this matter to your audience?

- An extractive deal, usually finalized in a contract between the national government and an extractive company, should balance the interests of the government, the company and the local community. It is often difficult to tell whether there are enough benefits and protections for the different actors until after the deal is finalized.

- The deal includes how much money the government is going to get, for what, and what the company has to do, when.

- Sometimes companies try to take advantage of loopholes in deals, which can cost the government millions. For example, the Australian tax authorities recently made Chevron pay USD 300 million after Chevron tried to avoid taxes by using intra-company loans as a means of shifting profits.

- In some countries, governments feel they have not got good deals, either because they did not understand the industry or due to corruption among the negotiators. Some bad deals have lost countries billions, such as the contract signed by the government of Guinea with Beny Steinmetz Group Resources (BSGR) in 2008 for the Simandou iron mine.

- Journalists and civil society around the world have used contracts to hold governments and companies accountable. By following up on small terms about the timing of project cycles, civil society in Belize effectively put an end to oil drilling in protected coral reefs.

- If deals are kept secret, it is difficult for reporters and other oversight actors to keep track of whether everyone involved is playing by the rules. Over the past 10 years, the details of some deals have been made more public, but much work is still needed to make sure they are being followed with citizens’ best interests in mind.

The basics

Each natural resource extraction project has rules governing the rights and responsibilities of governments, companies and citizens. These are defined through a country’s constitution, laws, regulations, policy and the contract between the government and a company for a particular project. Contracts contain project-specific rules, often in categories, including exploration and development, operations, who will make and receive what payments, social and environmental impacts, health and safety, and requirements for whom the company should hire to provide labor, products or services. It is hard to tell whether any part of a contract represents a good deal by itself. Yet as more and more contracts become available publicly, reporters can play a vital role in taking a critical look at whether a deal strikes the right balance between the costs and benefits of all its different terms. To report effectively on whether a deal is good for a country’s people, it’s also important to look at whether its terms are being met. When companies try to avoid their obligations, especially financial, this can result in huge potential losses — losses which journalists can help expose.

-

Legal frameworks: The rules of the game

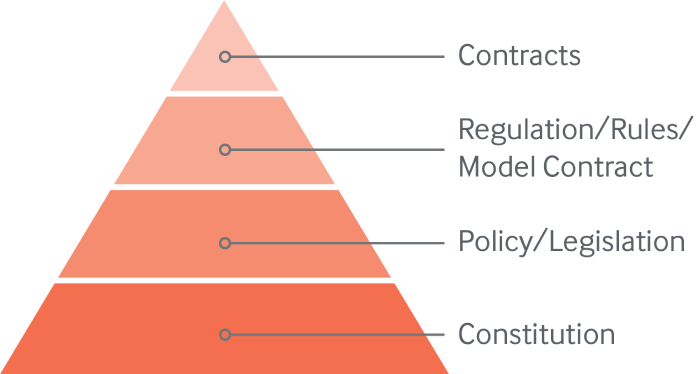

For each project to extract natural resources from the ground, there are rules that govern the rights and responsibilities of governments, companies and citizens. Together these rules are called a legal framework, or legal architecture. The rules can be written through a combination of the contract, regulations, policy, laws and the constitution (see the pyramid image below). Moving from the bottom of the pyramid to the top, each part of the framework usually becomes more project-specific and detailed. All the rules in the different parts of the pyramid should be consistent with each other. Often laws and policy have more authority than a contract—in legal terms, they take precedence.

The legal hierarchy. (Source: NRGI) When trying to assess the rules for a particular project, it is useful to understand how all these different documents fit together. Some countries have constitutions, laws, and regulations that are very specific about the rules governing the extractive industries. As a result, there may be less information in contracts and less for governments and companies to negotiate in each deal. Other countries have vague laws that leave more space for negotiating contracts. In this sense, a country’s legal framework around extractives can be characterized as being more “law-driven” (relying on permits and licenses) or more “contract driven” (relying on individually negotiated agreements between the government and a company).

→ This 10-minute video provides an overview of legal rules that govern the extractive sector.

What is a contract?

When governments decide to develop natural resources, they usually enter into agreements with companies, giving companies the right to extract natural resources in exchange for a share of the profits. These agreements go by many names, including contracts, licenses, concessions or permits.

An extractive deal is made up of many different contracts or agreements. The main “contract” is called a “state-investor” or “host government” agreement. This usually has annexes and amendments which can also be important. To get a full understanding of a particular deal, it is helpful to see additional environmental documents.

For many extraction projects, the terms of the contract remain secret between a few people in government and the companies involved. In the past decade, however, numerous companies and governments have started disclosing these contracts, so that different stakeholders can understand them and check whether the rules are being followed. All countries that are part of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) must disclose contracts signed or amended after 1 January 2021. This means that if a reporter cannot access a contract in a country or for a particular project, it will be easier to argue that it should be publicly available.

The document of the contract includes a lot of vital information about a project. A contract usually begins stating the official names of the companies involved in the project. It then describes rules, usually referred to as terms, for the government and companies. The terms are often divided into categories, including the following:

- Exploration, development and operations: This includes agreements about how often and what type of extraction can take place, when and how the company must report its plans to the government, and how long the company has to meet certain benchmarks. Many activists have found checking whether operational obligations are followed is a key way to get accountability for company behavior.

- Fiscal terms: These are the agreements about who will receive what payment for the extraction. There can be a lot of variety in these terms, so they are described in detail in the section below.

- Social and environmental impacts: These terms usually include broad parameters about what companies are obliged to protect and specific rules about when the company is required to report to the government on its impacts.

- Health and safety: These terms cover the health and safety of employees and day-to-day operations. There may be specific requirements for particular types of processing (for example, for mercury), but usually the terms refer to international standards or national health and safety law.

- Local content: This specifies any special requirements for whom the company is supposed to hire, either to work at the extraction site or to bring products or services to the project. Sometimes there are minimum requirements for the number of local people to be hired for specific types of jobs.

- Stabilization: A stabilization clause locks in place the laws and rules at the time the contract is signed. This usually means that even if a country passes a different law years later, the company can still operate by the rules set out in the contract. This can be very important if a government decides to increase, for instance, a royalty rate. Companies can save large sums of money if a stabilization clause is inserted into a contract giving it a “low tax guarantee.” More recent contracts typically only stabilize key economic and fiscal terms.

- Choice of law and arbitration: This section sets out what happens if there is a disagreement about the contract. Usually, this involves going to an international arbitration tribunal because foreign investors often lack confidence in a domestic court system’s impartiality. International arbitration can be controversial, due to its expense and secrecy.

The entire contract is ideally an effort to balance the costs and benefits of these different terms. It is hard to tell whether any term represents a good deal by itself, making it important to look at the overall picture of a deal and the global price of the commodity in question.

The document of the contract usually sets out these rules, but who checks whether they are followed depends on a country’s monitoring framework. Although one ministry is involved in negotiating the contract, many ministries are often involved in monitoring its specific obligations. For example, the ministry of the environment might be responsible for monitoring environmental impacts, while the ministry of finance might be responsible for monitoring tax payments. This can mean that several ministries need to work together to assess whether a company is doing everything it promised.

-

Fiscal regimes: Rules for revenue

A fiscal regime is the set of rules (such as taxes, royalties, and dividends) that say how the revenues from oil and mining projects are split between the state and companies. A country has many factors to consider when it decides which fiscal tools to use and how to use them. The most important concern is often how to balance maximizing future tax revenue with attracting investment. Higher tax rates can deter investment, but lower tax rates can mean a country does not benefit fully from its natural resources.

Some of the broad considerations include:

- What is the timing of the revenues?

Some fiscal tools provide governments with more money early in the lifecycle of an extractive project, while others do not deliver significant revenues until the project has already made a profit, which can take years. For example, signature bonuses generate revenues early in the extraction project, while profit-based taxes tend to be paid only after a few years of extraction, once a company’s costs (capital expenditure) have been recouped. - How does government revenue change when profitability changes?

As commodity prices, production techniques, and production rates change over time, so does the profit margin for the project. The fiscal regime can affect the government’s share of the profits when the project’s profit margin increases in three ways:- Neutral fiscal regimes give the state the same share of revenue whether profitability increases or decreases.

- Progressive fiscal regimes give the government a larger share of the profit when profits increase, and a smaller share when profits decrease.

- Regressive fiscal regimes give the government a lesser share as profits increase, and a larger share as profits decrease.

Each option can be beneficial depending on the desired outcome. Progressive fiscal regimes encourage investment, while regressive fiscal regimes provide a more predictable stream of revenue to the state.

- Who carries the risk?

Not all extraction projects are successful. Fiscal terms are usually agreed very early in the project, before extraction is underway. A company’s investment in the expensive infrastructure and supplies necessary to extract natural resources represents a risk, as the investment may not equal future profits. With some fiscal packages, a government shares more of the risk with the company and is subject to losses when a project is not profitable.

Watch this 10-minute video to learn more about fiscal regimes.

→ Read this NRGI primer about fiscal regimes to obtain an overview of the most common fiscal tools.

Tax incentives in mining

Read more

Many resource-rich countries offer tax incentives to attract investment in the extractive sector. In general terms, a tax incentive, or tax break, is any special tax rule that allows the company to pay different taxes from those which a company usually would. However, tax incentives are controversial. Companies argue that they are necessary to encourage costly investments in projects with high levels of financial and operational risk. Yet tax breaks can also result in significant losses of public income.

The most common incentives offered to companies by governments are tax stabilization and corporate income tax incentives, even though these are generally considered less efficient in attracting investments because they benefit profitable projects more than less profitable ones. It is more common for countries to grant incentives in the law, such as mineral or tax codes, than in project-specific contracts—except for reduced royalty rates, which are more often found in contracts.

Citizens in resource-rich countries are increasingly questioning whether tax incentives make the country lose out on the full value of its resources. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has produced a guidance note to help governments analyze tax incentives in order to maximize their tax benefits. This is also useful to help journalists assess tax incentives provided by the government.→ See this short video by Highgrade Media about ways to reduce tax incentives.

- What is the timing of the revenues?

-

Special challenges in monitoring fiscal terms

Some companies try to minimize the amount they must pay to the government using various loopholes. These different practices are known as “tax base erosion and profit shifting”, or BEPS. The extractive industries are not the only sector where this is an issue, and global reforms are underway in an initiative led by the OECD and the G20.

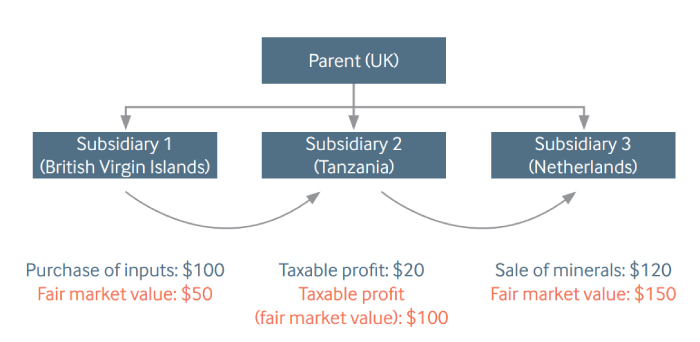

Transfer pricing

Transfer prices are prices used in transactions between related companies—for example, if a bulldozing company is owned by the same people as a mine, the mine can transfer profits to the bulldozing company. A company could manipulate transfer prices to move its profit to different jurisdictions, so it had to pay less tax overall. Under-reporting the value of production sold to related entities and over-reporting charges from related contractors, including for debt, are the main transfer pricing risks which tax authorities need to monitor closely.

Illustration of transfer mispricing in the mining sector (Source: NRGI) Under-reported project revenues

One way companies can try to reduce their tax bill is by under-reporting the value of the mineral product they extract and sell. They can do this by:- under-reporting the quantity or quality (the grade of raw minerals) of the principal commodity produced

- failing to declare valuable by-products, such as the small quantities of silver typically found in the same ore as gold

- under-reporting the market value of the commodity, by selling at a reduced price to an affiliated company.

For example, despite having negotiated generous fiscal terms, Mozambique lost revenue on an important natural gas project when the company running the project, Sasol, secured an agreement to sell the gas to its affiliate at a fraction of its value.

Production costs

Another way that companies can potentially decrease payments to a host government is by increasing their production costs. A company can do this by spending more on production than is necessary or efficient. A darker scenario involves companies over-reporting production costs through inaccurate accounting. Governments can prevent this type of abuse by increasing the monitoring and auditing of the company’s production costs. In Tanzania, the government created the Tanzanian Mineral Audit Agency (TMMA) in 2009 after discovering that leading goldmining companies were claiming large losses every year to avoid paying income tax. TMMA contributed to a substantial increase in government income from the sector by assessing the quantity and quality of minerals mined.Thin capitalization

“Thin capitalization” is a very important and common practice. It may occur when a country allows companies to deduct the interest payments on loans from their taxable profits. This creates an incentive for companies to take out bigger loans, whether or not they need them. Loans can even be made by companies that are part of the same multinational group. In this way, costs to the company that directly owns the asset are increased, which reduces taxable profits. Profits can be taken by a related company, often incorporated in a low-tax jurisdiction, in the form of interest payments. A country can reduce this loss of tax revenues by limiting interest deductions or restricting the debt-to-capital ratio.→ This report, published in 2018 by Oxfam, explains the many challenges governments face when auditing production costs for petroleum projects.

Story leads

Research questions and reporting angles

Below are story angles for reporting on an extractive deal in a particular country, based on a sequence of research questions. See Chapter 1 for more general story planning guidelines.

Coronavirus disclaimer!

-

A. Is the contract for this project a good deal?

1. Understand the broad plan. Any deal is a mix of compromises and balancing different interests. Asking whether something is a “good” deal means wondering which of those interests are most important. Considering various perspectives will help understand the big-picture interests that the country needs to prioritize in extraction.

- Investigate government documents. Reviewing national extractive policy documents can help uncover these broad trade-offs. Resourcedata.org is a large database of laws and policies on extractives from over 80 resource-rich countries. It is searchable by country or content area (under “Precept 1”). Strategic impact assessments and national mining or oil and gas policy documents can provide specific insight into how a government intends to balance trade-offs such as short-term versus long-term interests, or national versus local impacts.

- Ask key players. Interviewing sources in government and oversight actors about the government’s overall priorities for extraction can help in deciding what types of criteria to use in assessing whether a deal is “good”.

- Ask observers. Industry and non-profit observers can often offer useful perspectives on what a government has indicated are its priorities for approaching extraction. Connecting with observers who are familiar with the country over time can provide strong background material.

2. Find the terms of the deal. The terms of the extraction deal will be split between the constitution, laws and contracts, depending on the country. Usually, the contract will note any references to national law.

- Look for the legal framework. Possible sources include:

- Resourcedata.org, which allows users to filter documents by country and by individual precept of the Natural Resource Charter, a governance framework that covers the decision-making chain. Precepts relevant to finding the terms of an agreement include Precepts 4 (Taxation) and 5 (Local effects).

- EITI. The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) requires member countries to describe the legal framework and fiscal regime that apply to their oil, gas and mining sectors. Published on an annual basis with a time-lag of 1–2 years, reports can be found on the international EITI website or national websites. While project-specific data is often delayed, the broad descriptions can be helpful towards understanding the industry and where to find current information.

- Industry guides. International consulting companies publish annual guides about fiscal regimes in different oil, gas, and mining countries. These can be a good resource for comparing a specific deal with the general framework. They also can help reporters identify which are the most current laws in the sector. See EY’s guide on oil and gas and Pricewaterhouse Cooper’s guide on mining.

- Look for the contract itself. Possible sources include:

- Resourcecontracts.org. This online database contains publicly available oil, gas and mining contracts.

- Government sources. Many countries publish contracts they sign with extractive companies on ministry websites or through a dedicated portal. In some cases, the online cadastre system will list the terms associated with each license. From 2021, EITI implementing countries will have to publish all contracts.

- Company websites. Some companies, such as Total, Tullow Oil, and Rio Tinto, have committed to making contracts publicly available, provided their government counterpart has no objection. Other listed companies may publish selected terms of contracts to their investors, in particular, fiscal terms. These may be available in regulatory filings in the relevant stock exchanges or on company websites.

3. Analyze the trade-offs within the deal. The following angles of analysis are useful for assessing a contract:

- Assess the deal against objectives set out in the national strategy. Does the deal support the country’s goals as set out in its big-picture documents or strategies? Does it make economic sense? Does it provide more benefits than costs socially, environmentally and to the local economy?

- Compare the deal against the relevant law. Do the specific terms in this deal vary from what the law generally suggests should take place? This can be a time-consuming exercise, so it can be helpful to prioritize provisions to focus on. For financial provisions, one shortcut is to consult the industry summary guides for taxes (such as EY’s guide on oil and gas) and compare them against the specific details within this contract.

- Investigate potential deviations. If there is a difference between what the law says and the terms of the contract, follow up with human sources to understand why the government might have made concessions for this deal and whether these were reasonable.

- Consider the whole deal. When looking at a deal, it is important to take into account the overall balancing act between different provisions, including the fiscal regime, compensation for social-environmental damage, local content, profit sharing and debt terms.

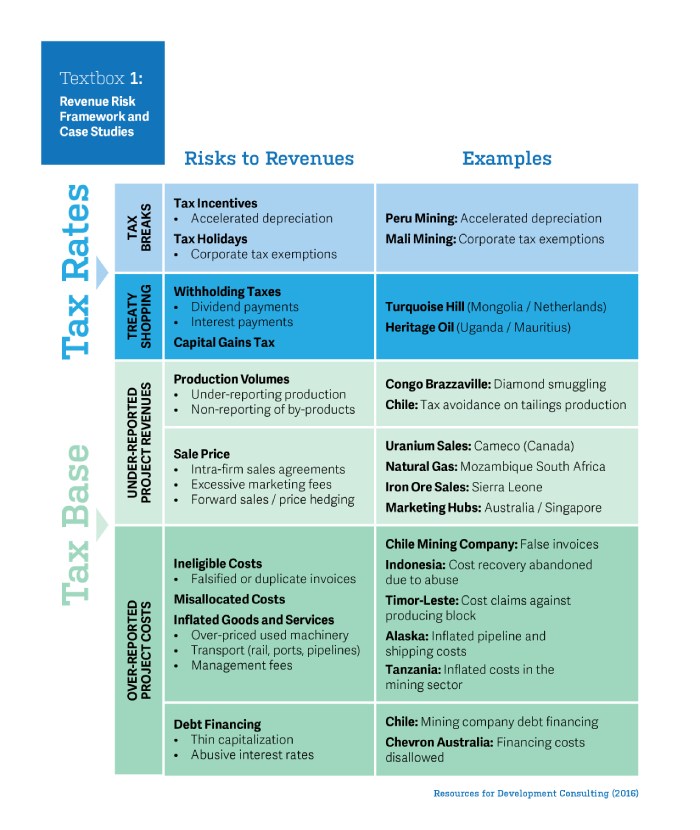

- Assess the financial terms. A key indicator of whether a deal is good for the country is whether government revenue loss is likely under the terms. The table below provides an overview of key risk factors that can negatively affect the government’s ability to benefit from a deal through tax revenues. It shows the differences between risks related to the tax rate and risks that affect the taxable revenues. The table can help show how well a government has crafted a deal to guard against these risks. Detailed financial modelling of economic and fiscal terms is needed to fully assess some of these risks. Constructing such models requires experience. Alternatively, reporters can ask civil society or industry experts for their understanding of the risks related to the fiscal terms.

Revenue Risk Framework developed by Resources for Development Consulting (2016) - Consider local content provisions. For many countries, a way to make sure the project benefits the local economy, beyond generating revenue, is by including in the deal provisions that require the company to hire local labor and procure services and goods locally (See Chapter 6). What are these “local content” targets in the contract and are they appropriate? Does the deal give priority to employing local people and locally based firms, and do local workers have the required skills?

- Review environmental and social impact provisions. What are company obligations to prevent, mitigate and compensate for environmental damage from extraction? Are there any fees the company should pay in compensation? Does the deal discuss responsibilities for financing and carrying out plans for closing the site and restoring the land? Are community development plans considered? What does the deal say about compensation for resettlement?

- Review infrastructure gains the project could bring. Is the company going to construct a road, railway, port or other transport infrastructure? Does the deal say whether the infrastructure will be available solely for the company’s use, or will it be available for other local mining companies or public use? Do the terms indicate if project power supplies will also be available to local populations?

- Consider the overall picture. Are the trade-offs clearly explained and do they make sense? Contact experts (see “Sources” below) for advice on how to evaluate the overall balance within a deal. Try to mix information gathered through desk research with conversations and interviews with public and company officials and local community members. Civil society groups in the capital or working with communities can also give useful perspectives.

- Consider the deal against others in this sector or region. To assess whether a deal is favorable to the state, look at similar contracts to assess whether it contains major differences from standard industry practice. Compare contracts that refer to similar minerals and transportation options.

- Find similar deals. Use resourcecontracts.org to find similar deals on similar minerals in your own country or neighboring countries. Make sure the mineral is the same and that the agreements are no more than a few years apart. It can also be useful to compare deals beyond your region, as long as they share points of comparison, such as type of extraction (off-shore or on-shore drilling, open pit or underground mining), maturity of the extractive sector, geological prospects, political and economic stability in the country, and proximity to end-market. For example, terms in oil and gas contracts in Senegal could be compared with those in other new producers like Mauritania, Mozambique, Tanzania or Guyana, but not with established producers like Norway or Kuwait.

- Check whether terms are comparable. In the oil, gas and mining industries, there can be legitimate differences between deals. Is the process for extracting the mineral the same, or do the projects use different mining techniques or drill at vastly different depths off-shore? Was the likelihood of finding commercially viable resources roughly the same when the deals were struck or was one much riskier than the other? Is the general infrastructure (transportation, power) in each country of similar reliability? What are the governance levels within each country, including political stability and absence of violence?

-

B. Are there signs that the company is not fulfilling its promises?

Because of the complexity and variability involved in extraction projects, it is unlikely that a reporter would be able to gather full evidence for whether revenue is being paid as required by law. It is more likely that reporters can look at the commitments made in a contract and check whether there are signs that what is happening does not align with expectations. In these cases, the story angle often calls for additional monitoring or explanation of how the contract terms are being met.

1. Understand the broad plan. Any deal is a mix of compromises and balancing different interests. Asking whether something is a “good” deal means wondering which of those interests are most important. Considering various perspectives will help understand the big-picture interests that the country needs to prioritize in extraction.

- Investigate government documents Reviewing national extractive policy documents can help uncover these broad trade-offs. Resourcedata.org is a large database of laws and policies on extractives from over 80 resource-rich countries. It is searchable by country or content area (under “Precept 1”). Strategic impact assessments and national mining or oil and gas policy documents can provide specific insight into how a government intends to balance trade-offs such as short-term versus long-term interests, or national versus local impacts.

- Ask key players. Interviewing sources in government and oversight actors about the government’s overall priorities for extraction can help in deciding what types of criteria to use in assessing whether a deal is “good”.

- Ask observers. Industry and non-profit observers can often offer useful perspectives on what a government has indicated are its priorities for approaching extraction. Connecting with observers who are familiar with the country over time can provide strong background material.

2. Find the terms of the deal. The terms of the extraction deal will be split between the constitution, laws and contracts, depending on the country. Usually, the contract will note any references to national law.

- Look for the legal framework. Possible sources include:

- Resourcedata.org allows users to filter documents by country and by individual precept of the Natural Resource Charter, a governance framework that covers the decision-making chain. Precepts relevant to finding the terms of an agreement include Precepts 4 (Taxation) and 5 (Local effects).

- EITI. The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) requires member countries to describe the legal framework and fiscal regime that apply to their oil, gas and mining sectors. Published on an annual basis with a time-lag of 1–2 years, reports can be found on the international EITI website or national websites. While project-specific data is often delayed, the broad descriptions can be helpful towards understanding the industry and where to find current information.

- Industry guides. International consulting companies publish annual guides about fiscal regimes in different oil, gas and mining countries. These can be a good resource for comparing a specific deal with the general framework. They also can help reporters identify which are the most current laws in the sector. See EY’s guide on oil and gas, and Pricewaterhouse Cooper’s guide on mining.

- Look for the contract itself. Possible sources include:

- Resourcecontracts.org. This online database contains publicly available oil, gas and mining contracts.

- Government sources. Many countries publish contracts they sign with extractive companies on ministry websites or through a dedicated portal. In some cases, the online cadastre system will list the terms associated with each license. From 2021, EITI implementing countries will have to publish all contracts.

- Company websites. Some companies, such as Total, Tullow Oil and Rio Tinto, have committed to making contracts publicly available, provided their government counterpart has no objection. Other listed companies may publish selected terms of contracts to their investors, in particular, fiscal terms. These may be available in regulatory filings in the relevant stock exchanges or on company websites. The OpenCorporates database can also be useful.

3. Select the term that will be the focus of the reporting. Many terms may seem important, but prioritizing investigation in one area can facilitate a clear story. Terms could include company payments, production levels, employment clauses, or social and environmental obligations.

4. Find reporting obligations for that term. Companies are usually required to report on how they meet the terms of a contract. It is useful to know where and when to expect those reports. Key sources include:

- The contract. When the contract is available, look for terms or sections that discuss the reporting obligations (often indicated in the table of contents). For some contracts, resourcecontracts.org offers a helpful advanced search function that allows users to search contracts via a set list of “annotation categories,” including reporting requirements.

- The law. Finding the applicable legal provisions often requires checking different pieces of legislation. For instance, tracking employment terms in a mining contract requires review of the mining code and the relevant employment code. Most contracts include references to relevant pieces of legislation under which the agreement falls, although it is important to check whether there have been any changes in the law since and whether they apply to the contract. If stabilization clauses have been included in contracts, changes in the law may not apply.

5. Check for company reporting. The types of information available will differ depending on the obligation. This list focuses on where to find reporting of financial terms, but it can also be used to look for reporting on other information. Likely sources include:

- Resourceprojects.org This database compiles payment information released by companies subject to mandatory disclosure laws in the EU, Norway and Canada. Users can review the data by country or by company to check whether there are payments related to a particular deal.

- Company reports and statements. Publicly listed companies are usually required to file numerous reports, including quarterly and annual reports, country reports, stock exchange filings (such as the F-20 form on the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission) and sustainable development or corporate social responsibility reports. The OpenCorporates database allows users to search public domain documents available from over 185 million companies.

- EITI. Companies operating in countries that have joined the EITI must provide information about their activities, which are then reconciled with figures provided by the state. The EITI Standard sets a series of reporting requirements for companies to submit data about their tax filings, production, employment rates and social expenditures.

6. Consider whether reporting meets expectations. Again, these suggestions focus on reviewing financial terms, but similar tactics can be used for checking other types of terms.

- Cross-verify. When reporting information is available in multiple locations, check across those reports to see whether figures are consistent. This could mean checking a payment in an EITI report against one in a stock exchange report, or checking a payment figure from a company against a revenue figure from a government entity. There may be legitimate reasons why these figures differ, so additional investigation will be necessary after this step.

- Check figures against calculated expectations. When one figure, like the total royalty revenues from a project, is available, then reporters can use the production figure and the royalty rate to see whether the figure meets expectations. It is important to interview industry and government officials when discrepancies occur, to see whether there are legitimate reasons for differences.

- Look for trends. Extraction projects usually follow a similar trend of exploration, development, production and closure. The cost and revenue curves over the lifecycle are usually similar across projects. Charting the data available over time can show whether a project is deviating from an expected curve. If so, reporters can ask additional questions of human sources to find possible explanations.

- Ask experts. Interviewing industry and civil society experts about their expectations for a project at a particular phase is a helpful way to understand whether a company report is in line with expectations. Often these interviews can also give direction for further research.

7. Check for government monitoring of a term. The government and oversight actors are likely to have formal responsibilities to monitor whether a term is being fulfilled. Understanding the government resources for monitoring that term can help inform stories as to whether companies are likely to be held accountable if they fail to meet obligations.

- Find out which ministry is responsible for monitoring a term. The contract term or the associated reporting often describes the ministries involved. EITI implementing countries usually give a good description of different ministries’ roles in the introduction to their annual EITI reports.

- Consider ministry monitoring practice. Ministries often have set ways for how they like to monitor an extractive term. Interviewing industry experts, government officials and experts from international organizations like the World Bank can reveal good practice for particular terms.

- Consider ministry resources. Understanding the tools, revenue, and number of employees the ministry has available to conduct monitoring can suggest its priorities. If these figures are not readily available, interviewing ministry staff or filing freedom of information requests can be effective.

-

C. Is information about the deal reasonably available?

1. Establish what the rules are for contract transparency. Key places to look, apart from national sources, include:

- The Resource Governance Index (RGI). RGI country profiles may give an overview of contract transparency laws and practice. More detail can be obtained from the research findings for individual questions by downloading the Data Explorer. Under licensing in the “country profile” tab, users can find a country’s rules for making contracts public and whether this has taken place between 2015 and 2016. Answers to questions 1.1.9a, 1.1.10a, and 1.1.10b in the Data Explorer include links to the legal framework related to contract transparency.

- EITI reporting. The EITI requires member countries to describe their policy on contract disclosure. For countries with a proactive disclosure policy, this includes an overview of contracts already in the public domain and information about where to find them. All member countries will be required to make any contract signed or amended after 1 January 2021 public through their government websites. Those reports are usually published annually and can be found on national EITI websites or the international site.

2. Compare a country’s transparency law and practice with other countries.

- The Resource Governance Index. The “value realization” aspect of the RGI includes several questions on different aspects of licensing. The Compare Countries tab of the website can compare up to three countries on different aspects of the index. Under the licensing component (under “Value realization”), users can compare country performances on the transparency of contracts.

- The RGI data explorer allows for more detailed investigation and comparison of each licensing question, with explanation of the results and links to underlying source documents. This can be used to compare countries or entire regions.

3. Compare a country’s current process to global standards. Transparency is at the core of understanding a deal and monitoring obligations. A reporter can look for previous assessments of the country’s transparency or compare the country against good practice.

- EITI Validation. EITI-implementing countries are checked, or “validated,” to assess whether they are disclosing information in line with the EITI Standard periodically. A detailed validation scorecard is available on the national and international EITI websites. The scorecard will show whether the country made progress in disclosure for each of the expectations around contracts. There is a brief explanation for each score.

- Good practice. Looking at good practice guides, such as Open Contracting for Oil, Gas, and Mineral Rights by NRGI and the Open Contracting Partnership, can give detailed perspective on what is ideally expected.

4. Follow up with human sources. Ask public officials or relevant staff at the regulating agency whether they have considered how other countries do in comparison and why a particular country is less transparent. Their explanation of differences can bring the latest issues into the analysis.

Coronavirus disclaimer!

Examples of good reporting practice

The examples given below can provide inspiration while preparing stories on extractive deals. Some highlight day-to-day reporting, while others are in-depth investigative reports.

-

Taxes and transfer pricing in Namibia (investigative)

Mines on tax honeymoon

This article investigates why 30 mining companies’ tax payments combined to be far less than the taxes of one joint venture between the government and De Beers in Namibia. It was the result of a three-month collaboration between the investigative unit of the Namibian, a national daily newspaper, and Finance Uncovered, an international investigative journalism non-profit.The story poses questions based on data from the Chamber of Mines of Namibia, national budget documents and mining companies’ annual reports. It explores their implications through interviews with various industry and non-profit experts. Additional articles on this topic could strengthen the impact of this investigation by helping the reader understand the impact of the tax payments on their lives.

-

Fiscal terms after election in the DRC (day-to-day)

Mining amid regime change in the DRC

The election of a new President in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is the starting point of this article in the regional Africa Business Magazine. The story looks at how the new president is likely to implement the recently amended Mining Code and how this is perceived by foreign investors. Using a news hook, the article offers an overview of DRC’s mining sector and current tax regime. The analysis is grounded in facts and digestible figures and is complemented by quotes from expert interviews. Concrete characters, such as a newly elected political leader, make the story easy to follow. The article was well shaped for its business audience. To be relevant to a national audience, it could discuss the implications of revenue loss on the DRC’s budget. -

Loss of government income in the exploration phase in Nigeria (investigative)

How Nigeria loses trillions of Naira to deep offshore oil operations

In this well-researched article, the Nigerian Premium Times highlights how Nigeria is losing money in the oil exploration phase due to an outdated law which applies royalty rates unfavorable to the Nigerian state. The reporter does an excellent job of putting into context the complex topic of royalties. To do so, he presents key facts to help his audience understand why this topic matters to them. He then uses examples from other countries to put the Nigerian experience into perspective. Data visualizations support his explanations and help the reader grasp complex calculations behind royalty rates. The reporter ensured his piece is balanced by bringing in various expert voices and explicitly stating when interview requests were refused. -

Impacts of fiscal stabilization clause in Burkina Faso (investigative)

Low tax guaranteed: how a Russian mining giant has saved $16.5m in Burkina Faso

This story, published in the national L’Economiste du Faso and regional Cenozo, revealed the money saved by a giant Russian mining company thanks to a fiscal stabilization clause. Journalists working in Burkina Faso and London noticed Nordgold, a major Russian mining firm, boasting in its annual report about a favorable tax deal on a gold mine in Burkina Faso.The journalists obtained the gold mine contract from sources and government gold production data from the mine. Working with these documents, they were able to calculate tax paid at the favourable “fiscal stabilization” rate. They then compared the amount to what the mining company would be paying if it did not have a fiscal stabilization clause. The difference—USD 16.5 million—was more than the country’s entire school supply budget. The article does well to contextualize these figures in the real poverty experienced in Burkina Faso and the wealth of those in the mining industry. To provide balance, the reporters also incorporated perspectives from the mining company and industry experts.

-

Behind the scenes of contract investigations in Burkina Faso: Testimony by Finance Uncovered co-Founder Nick Mathiason

Nick Mathiason has been a business and finance journalist for close to 30 years and has broken a sizeable number of impactful stories that have had international prominence.

One of the first UK journalists to report on industrial-scale tax avoidance, in 2012 Nick founded and today co-directs Finance Uncovered. The non-profit organization focuses on training and supporting journalists covering illicit finance-related news.

In 2018, Nick partnered with Cenozo – the Cell Norbert Zongo for Investigative Journalism in West Africa – to research a story about an unusually favorable tax deal obtained by the Russian gold mining company Nordgold in Burkina Faso. The story was eventually published in L’Economiste du Faso and showed that the stabilization clause granted to Nordgold cost the government of Burkina Faso USD 16.5 million in mining royalties.

Nick agreed to be interviewed via Zoom to share insights about the investigation. You can watch the interview here or read the full transcript below:

Transcript

Full transcript

1. In 2018, you published an article about the terms of a contract signed by the Russian mining company Nordgold with the government in Burkina Faso. What is the story about?My name is Nick Mathiason. I work at Finance Uncovered and with Cenozo – the West African Investigative Centre – and L’Économiste du Faso in Burkina Faso, we produced a story, nearly two years ago, which revealed that citizens of Burkina Faso missed out on an estimated $16.5 million in gold mining royalties that could have funded vital public services. They missed out on these royalties thanks to a special a low-tax deal that the former dictator made with a big Russian company.

2. Where did the idea for the story start and how did it evolve?

The story goes back quite a long way. Quite a few years ago I attended a conference looking at African tax avoidance. One of the delegates was talking about how progress in this area wasn’t happening. They made some policy progress, but then they discovered that there were these things called fiscal stabilization clauses in oil contracts which basically gave low-tax guarantees and overrode national legislation, so progress in terms of transparency, they were arguing, was limited. And I thought to myself “this issue of low-tax guarantees or fiscal stabilization clauses is very interesting, I’d like to one day do something about that.” And then about two and a half years ago, I was working with a great journalist, who was coordinator for Cenozo, which is the West African Investigative Federated Centre, they kind of are an umbrella organization and the name of the journalist was Daniela Quirós-Lépiz, and she was very keen to do some work on Burkina Faso gold companies and looking at the contracts there. And so we started looking at the biggest gold companies in Burkina Faso and one of these companies was Nordgold. And as we look through their accounts which, they’re a [publicly listed] company or they were at a time, and so we could look through their accounts. And we were looking at the sections in Burkina Faso where they were producing gold, though they were producing gold all around the world. But in Burkina Faso we could see that one of their mines had a very low tax rate, which the company was boasting about to its investors. So we thought there could be a story here, and so that’s how the story started really.

3. How did you investigate the story and what were some of the challenges?

We started building up the research by, first of all, looking at all of the publicly available accounts that Nordgold produced. And we could see that they had this special fiscal stabilization clause, which they were boasting about in their accounts. So the next step was to look at the Burkina Faso legislation to double check what the royalty rates were, because basically Nordgold got a special royalty rate at Taparko and we had to check how that compared with the national legislation. So we could see that they got a three percent royalty rate, no matter what the gold price was, and we could see a national legislation in Burkina Faso, depending on what the gold price was, the royalty rate moved. The higher the price, the higher the royalty rate. We could see that during the last few years the gold price was pretty high, so the royalty rate was moving to between 4 and 5 percent whereas, Taparko only had a royalty rate of 3 percent, so we can see they were benefiting very much from having this fiscal stabilization cause. Now it wasn’t very easy to get the information about how much gold was being produced from this specific mine. We worked with a journalist at L’Économiste du Faso, Elie Kabore, who is a great journalist. He’s a member of Cenozo and he worked with Daniela in order to get information out of the Burkina Faso Ministry of Mines. So we got official gold production rates coming out of the Ministry of Mines and we also got how much royalties Taparko (as well as other gold mines in Burkina Faso) was producing. We knew that the royalty rate was just 3 percent, so it was quite easy to calculate how much gold would be produced if Taparko didn’t have a fiscal stabilization clause and if that gold had a royalty rate that all the other mines in Burkina Faso had, and we calculated that difference basically. And that was a team effort.

4. How did you ensure your story was reliable and balanced?

One of the jobs of journalists is to be fair and the other big job is to be accurate. And so we always have to get a company’s view and context. And so once we have the data, we have to fact-check it, give it to a couple of experts to make sure that they agree that we’re in the right place, and then we contact the company. And I think Daniela and Elie were the people who contacted Nordgold in Burkina Faso, but I was involved in trying to email their head office, as well as Daniela, so there were two organizations working together who are directly talking to the company, so that was quite helpful. And we also needed to understand that Burkina Faso’s kind of floating royalty rate was negotiated at a time when there was social unrest in Burkina Faso, where the gold price was going up and yet the economy wasn’t benefiting, so they needed to get more money into government coffers, so that’s when they did increase the royalty rate. So we needed to understand the wider context of this particular situation, but that’s part of making a story, part of making a decent substantial story is really trying to understand the context in which the country and the company were operating, as well as the actual social issues linked to what could be seen as a favorable tax rate.

5. What lessons can other journalists learn from your coverage of this story?

One of the lessons that journalists and researchers can take from this story is looking at the big mining or extractive industry companies operating in specific countries, and if they are quoted on stock exchanges then they will be reporting on specific countries where they operate, and they do actually report quite a lot of detail. So initially this story got off the ground because the company itself disclosed what they thought was a beneficial tax rate, and that was from publicly available information, so it’s really worth understanding the major global companies that are operating in a country that you’re focused on and then reading the reports where they describe the country-specific operations; they’re always disclosed in those annual reports and that can really take you places. Once you have that, then you can then start to ask experts or use your own experience to build up a story. That’s probably the primary lesson.

The other great thing is that it was good working in a team. We had people working in Burkina Faso and I was around to be a sounding board and also direct certain situations as well. So it’s good working in a team where there are different people with different experiences.

Sources

Below are sources that can contribute to different angles on stories about contract deals. Some will be similar across different aspects of mining, oil and gas reporting and are repeated across chapters, but others apply specifically to contracts. When possible, there are direct links to institutions in the main target countries of “Covering Extractives”: Ghana, Myanmar, Tanzania and Uganda.

Coronavirus disclaimer!

-

Public institutions

Government entities

Extractive deals usually involve a chain of government bodies, from negotiating the contract to enforcing the agreement and monitoring its implementation. In some countries, there is a team across ministries that works together for negotiations. For example, in Tanzania, the Minister of Constitutional and Legal Affairs oversees a multi-ministry negotiating team.Monitoring the terms of a contract involves several different entities. The ministry of finance often plays a prominent role in collecting taxes from companies in accordance with the deal. It might have a dedicated department for revenues from the extractive industries, which can give further insight into the income generated by a specific deal. Some revenues may be collected by different government agencies, such as surface taxes collected by local governments. In EITI-implementing countries, the EITI report should list all the government agencies that collect revenues.

Other government bodies involved in implementing and monitoring whether the parties fulfill the terms of the deal include the relevant environmental agency and different departments at the relevant ministries—including the one overseeing health and safety regulations, or responsible for checking production timelines. Some countries, such as Mexico, have independent regulatory agencies in charge of monitoring extractive resources (mining and petroleum), environmental protection or water preservation.

Oversight bodies

Parliament often has a mandate to approve or look into the deals signed by the government. In many countries, parliamentarians use that right to make enquiries about certain terms or to ask whether renegotiations are needed. For example, in Tanzania, the government can renegotiate contracts with mining and energy companies if they contain “unconscionable”, or unreasonable, terms.Independent audit institutions are another important source of information. They are entitled to investigate whether the deal was signed using proper procedures and whether it is being followed. Audit reports are usually submitted to parliament, meaning the minutes of parliamentary debates can provide further background. The U.S. Government Accountability Office, an equivalent body to a supreme audit agency, conducted a review of royalty collection in the United States which found that government receipts were significantly below market rates.

-

Companies

Companies often interpret the terms of a contract differently from the government or civil society. This may be informed by their corporate practice, investment strategy or experience with similar incidents. Companies are often unwilling to comment on the terms of a specific contract, but many will respond to questions about principles that guide their choices.

For publicly listed companies, it may be possible to find annual reports, investor presentations and technical reports on their websites, in stock exchange filings or in databases such as OpenCorporates. Private companies might also be required to release relevant information in their annual reports or their national company registries (such as Companies House in the U.K., Kamer van Koophandel in the Netherlands or the Australian Securities and Investments Commission).

-

Experts, civil society and watchdogs

National groups

Experts from civil society and academia can be helpful commentators on licensing and allocating rights. They can distance themselves from government or company interests and offer a different view of what is in the people’s interest. Note, however, that they too can be prone to biases. This is why it is important to look for second or opposing views.Where relevant, journalists are welcome to contact the NRGI country offices, where staff can provide connections with the right expert internally.

Other options for connecting with competent civil society or academic figures include:

- Publish What You Pay (PWYP), the global coalition of civil society organizations campaigning for a fair use of natural resources. PWYP has over 700 member organizations in 50 countries, working on numerous issues, including contracts. Its national coordinators are able to direct journalists to a range of expert contacts.

- In EITI member countries, there will be civil society representatives on the national multi-stakeholder group. The national secretariat could also offer recommendations for civil society groups that specialize in particular extractive deals or contract terms.

- Academic institutions may be able to lend expertise on particular types of contract terms, such as fiscal analysis or environmental monitoring.

International civil society

International policy groups and research institutes that produce valuable research on contracts and taxation in extractives include OpenOil, the Columbia Center for Sustainable Investment, and the International Center for Tax and Development. The International Institute for Sustainable Development is also useful, and hosts the Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development. -

International organizations

International institutions

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank all produce regular guidance and analysis on extractive taxation issues. They may be contacted either through country office experts or thematic experts, usually based in their headquarters.Serious disagreements about contractual issues between natural resource companies in a country or between investors and a government might be settled in an international arbitration court. Those include the International Court of Arbitration in Paris, the International Chamber of Commerce (which has arbitration panels in different countries), the World Bank’s International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes, and the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law.

The negotiation support portal is an online connection tool that can link host governments to support while they are negotiating extractive contracts. It includes a vast database of resources that can be used to support analysis of an extractive contract.

Multi-stakeholder initiatives

The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) is a multi-stakeholder initiative which supports transparency in resource-rich countries through an international standard implemented by members. EITI-implementing countries are required to annually disclose their legal framework for revenue collection. All EITI-implementing countries must publish extractive contracts entered into or amended after 1 January 2021. Although EITI data is often published slowly, the descriptive reports and the type of information available can be used as a basis for questioning ministries for more current stories. The national multi-stakeholder group that oversees a country’s EITI process can also be a source for discussions on what information about contracts should be available. -

Data sources

Legal frameworks

NRGI has been gathering thousands of documents related to extractive sector governance on its website, resourcedata.org. Documents can be sorted by country and by the precepts used in the Natural Resource Charter.

To support research into mining legislation in Africa, the World Bank has created the African Mining Legislation Atlas, a useful tool to navigate and compare mining codes in the region.

In Myanmar, journalists can access relevant laws and bylaws relating to extraction on the MEITI website and on the website of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation.Contracts

NRGI, together with the World Bank, the Columbia Center for Sustainable Investment and OpenOil, manages resourcecontracts.org, a directory of thousands of oil, gas and mining contracts. It features plain-language summaries of many contracts’ key social, environmental, human rights, fiscal and operational terms, and tools for searching and comparing contracts. Contracts can be viewed by country or resource, with advanced search options including searching by company or year signed, as well as by key clauses. The “Research & Analysis” tab showcases research and analysis using the site.Revenue payments

NRGI has a website called Resourceprojects.org which compiles data about revenue payments made by extractive companies based in the EU, Canada, Norway and the U.K. to host governments. The data are released through companies’ stock listings and are regularly added to the site, making it useful to sign up for notifications about new data uploads. The data can be filtered by individual projects and by government entities receiving the payments. NRGI has also prepared two briefings to showcase how the data can be used when deeper analysis is applied. One covers gold mining revenues in Ghana, the other, oil and gas revenues in Nigeria. Note also that the civil society coalition Publish What You Pay Canada has developed a short guidance note on how to access data submitted to Canadian authorities.Tax incentives

In 2019, the Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development launched a new database compiling tax incentives across 21 countries. The database can be downloaded as an Excel file for exploration. A helpful practice note helps users understand the information.

Voices

In the short videos below, a representative from oil company Total, the Chairman of the EITI Commission in Tanzania and a civil society representative from Guyana discuss the issue of contracts in the extractive industries.

Learning resources

-

Video resources

Several NRGI videos explain how a country establishes and implements its fiscal regime:

- The first gives the pros and cons of different types of system and gives reasons why governments might choose one over another.

- An 11-minute video outlines royalty and tax systems, detailing ways they can vary in terms of rates and bases.

- A video on Fiscal Regime Implementation discusses how countries try to implement fiscal regimes and some of the related challenges.

- UNU-WIDER has produced some shorter videos on taxation and taxing the mining sector, which use plain language and give an overview of the issues governments consider when creating a tax system, with examples from several countries.

High-Grade Media has a short interview with Alexandra Readhead, Lead on Tax and Extractives at the International Institute for Sustainable Development, explaining why certain tax incentive structures may not be serving countries as well as they expect.

-

Key reports

NRGI has drafted short primers on contract transparency , fiscal regime design and transfer pricing, which provide overviews of the topics in plain language. There are also longer plain-language manuals on oil and mining, created by a group of industry experts.

The accounting firm PriceWaterhouseCoopers has a useful guide to mining taxes and royalties, while EY offers a similar guide for taxes in the oil and gas sector. Both help readers carry out comparisons between different countries.

Publish What You Pay Canada has released a comprehensive report on the many ways that companies plan and avoid taxes.